Cities and the First Amendment. In order to exercise the right to assemble peaceably, people need a place to assemble, and cities provide these places. Last week’s demonstrations in Portland against the Trump Administration took place on symbolically important ground in the heart of the city. Tens of thousands marched along Naito Parkway and Governor Tom McCall Waterfront Park, and through the Japanese-American Memorial Plaza.

This is the place where, half a century ago, Portland tore out the Harbor Drive Freeway that cut off the city from its riverfront, and instead built a park. The Naito Parkway honors civic leader Bill Naito, who was among those pushed out of Portland in the early days of World War II by the federal government’s illegal “internment” of Japanese Americans. Cities are the places where we come together to seek redress of greivances and exercise these fundamental rights.

Must Read

Dreaming big should begin with starting small. Taylor Griggs of the Portland Mercury has a vital essay on our ambitions for the city’s transportation system. Area leaders are proceeding with billion-dollar-a-mile freeway expansion projects, rationalizing these expenditures as evidence that we can do big, beautiful things. But what they fail to ask is whether these very expensive–and getting more expensive–projects actually do anything to make our city, or our lives, better. Griggs points out that the bulk of the innovation and improvements in the city’s transportation system and quality of life have come from smaller and bottom-up ideas, not a handful of bloated highway projects.

I fully embrace abundance when it comes to dense housing, investments in bike and pedestrian infrastructure, and transit. Bring on the high-speed rail and the solar farms to power it. . . . But we can’t have all of these things and extra-wide freeways—not if we had the most generous federal partners imaginable, and certainly not in our current reality. Portland can, and should, still dream big. But we’ve got to give up the megaproject pipe dreams and get real.

In short, we shouldn’t do big dumb things, or big bad things, and the easiest way to avoid that is to start small, start local and think different. Which has always been the Portland way.

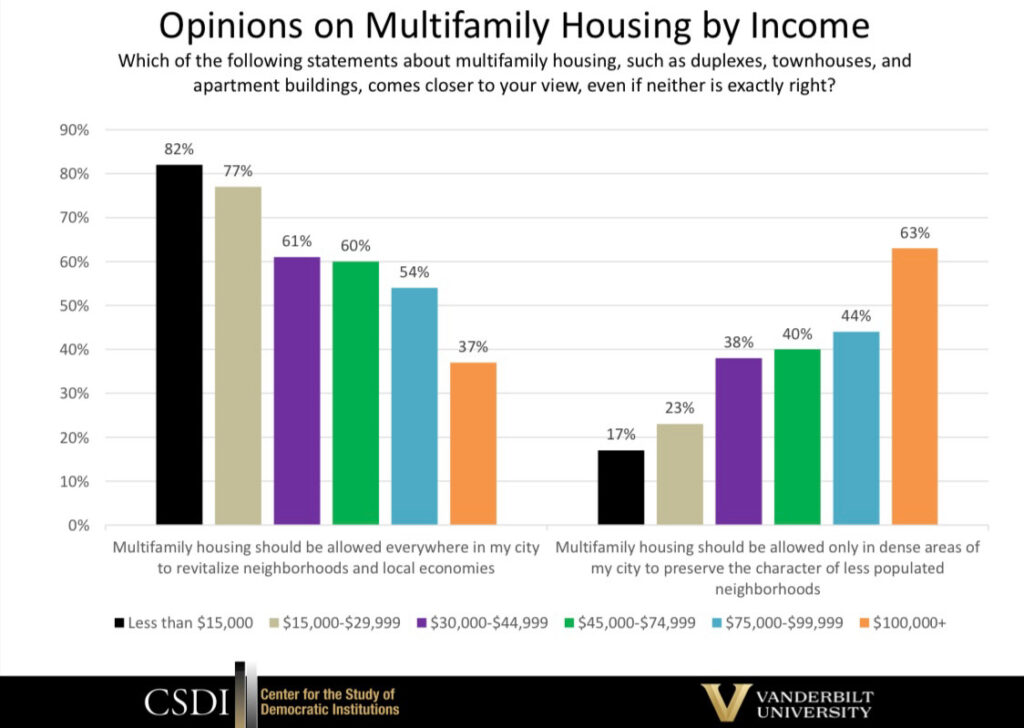

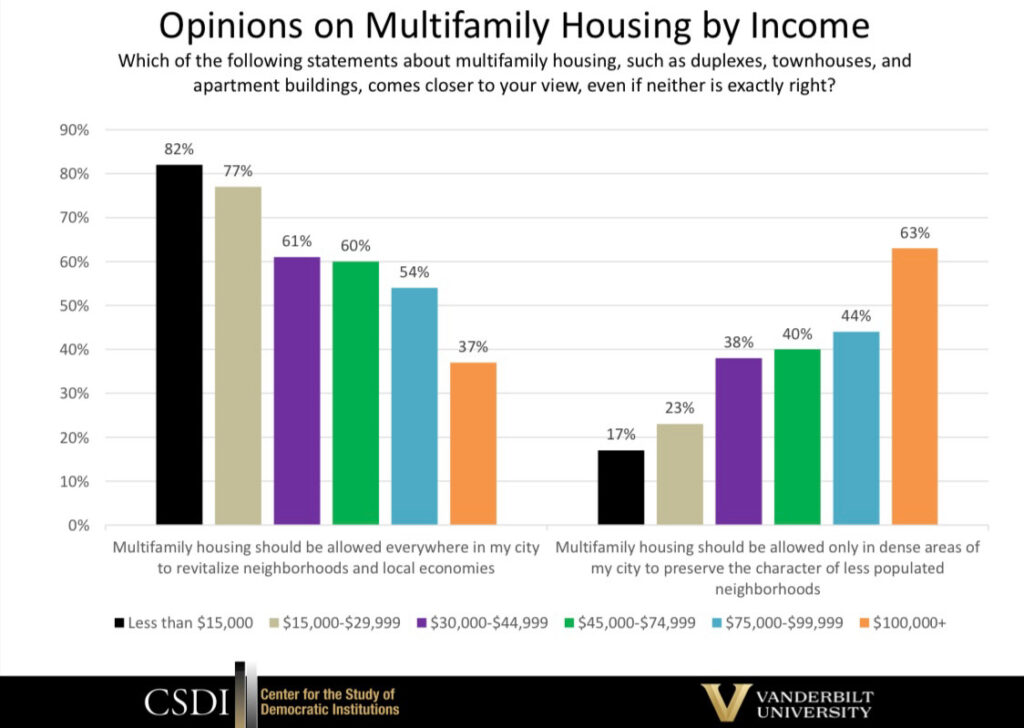

Strong support for multi-family housing, especially among lower and middle income households. The results of a recent public opinion survey from Nashville caught our eye. While there’s broad agreement that housing affordability and availability are big problems, we often seem to be at a loss to agree on policies that will remedy the situation; the supposed intransigence of NIMBY voters to more density is a major roadblock. The Vanderbilt Poll asked area residents whether apartments should be allowed “everywhere in their city” or only in a few, dense areas to preserve neighborhood character.

The results are strongly correlated with income levels. Lower and middle income households overwhelmingly support apartments everywhere. Only those with incomes over $100,000 want to restrict apartments to protect neighborhood character. We suspect that these results would also hold for other cities as well. If we’re concerned about equity, allowing apartments everywhere has strong support from the least affluent, and is only opposed by the wealthiest households.

Colin Daugherty goes full Kotkin. Writing at the New York Times, Colin Daugherty lavishes praise on sprawl as the solution to our housing affordability problems. It’s a view that’s long been expressed by

Joel Kotkin–who, surprisingly, isn’t actually referenced in the article. Daugherty makes the case that its cheap and easy to build on greenfields at the urban periphery.

Totally missing from this analysis is any examination of the transportation costs associated with such sprawl. As we’ve documented at City Observatory, there’s a huge

sprawl tax in the form of higher transportation costs. In addition, Daugherty gives no thought to the equity,

safety or environmental implications of low-density development. Suburban sprawl is intrinsically car-dependent; it makes it vastly more expensive to provide transit, relies on massive subsidies to highway construction. For those who don’t or can’t drive, it condemns them to second class citizenship. Daugherty repeatedly claims that infill housing and redevelopment are difficult and expensive, but this reflects a legacy of pro-suburban policies and subsidies that could be changed. Where policies restrict sprawl and incentivize redevelopment, its entirely possible to get a different pattern. In the Portland metropolitan area, in the past decade,

70 percent of the new housing has been infill, multi-family, or “missing middle”–like townhomes and duplexes, with only one third of new homes being single family buildings. And we’ve shown that Portland area residents collectively reap a billion dollar a year “

green dividend” because more compact development means they have to drive less and spend less on cars and gasoline. If you squint hard and look narrowly only at real estate listings, suburban housing might initially look cheaper, but if you consider the full social, fiscal and environmental costs, it is anything but. The challenge here is to think about affordable living, not merely cheap–and heavily subsidized–sprawl housing.

New Knowledge

The unintended consequences of LA’s “Mansion Tax.” Direct democracy in California has a long history of policies that poll well and have insidious unintended consequences (see Proposition 13). The latest of these is the Los Angeles Mansion Tax, enacted by voters in 2022. It seems like a simple, soak-the-rich proposition–imposing a 4 percent to 5.5 percent transaction tax on property sales over $10 million. The name makes it seem like it applies to mansion, but in reality, most of the property transactions subject to the tax are apartment buildings or commercial structures, like stores or offices. Facing these prodigious taxes, owners are reluctant to sell. A new study from UCLA’s Michael Manville and Mott Smith shows that there’s been a precipitous decline commercial, industrial and large scale residential property transactions. As the author’s write:

Measure ULA appears to be reducing higher-value real estate sales in Los Angeles, particularly sales of properties other than detached single-family homes. A reduction in such sales is troubling, because these sales directly and indirectly drive construction of much-needed new housing, and help create new commercial and manufacturing opportunities for workers. These sales are also disproportionately important to the city’s overall fiscal health, because they largely determine the growth in property tax revenues.

In addition to disrupting incentives to sell and redevelop properties–and add more housing–and penalizing sales of multi-family properties, this anlaysis shows the Measure ULA has produced vastly less revenue that anticipated. As with inclusionary housing requirements, taxes and regulations prompt rapid and large changes in investment that can swamp the hoped for positive effects of a policy. Manville and Smith offer some concrete recommendations for changing Measure ULA, in effect, so that it only applies to mansions, i.e. very high value single family homes. That’s probably what voters thought they were doing when they adopted the measure three years ago.

Michael Manville and Mott Smith, The Unintended Consequences of Measure ULA, Lewis Center for Regional Policy Studies, University of California, Los Angeles, April 2025.

In the news

City Observatory director Joe Cortright was interviewed by KGW-TV about the multi-billion dollar cost-overruns that are behind the Oregon Department of Transportation’s budget problems on April 3.

Follow City Observatory on Bluesky.