What City Observatory Did This Week

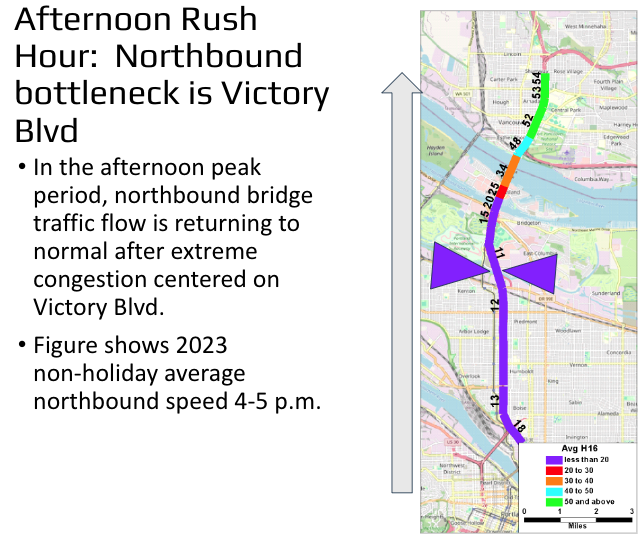

They’re digging in the wrong place: A new, independent analysis by national traffic expert Norm Marshall of Smart Mobility, Inc., shows that the proposed IBR project fails to fix the real bottlenecks affecting I-5 traffic. The Interstate Bridge Project proposes spending $7.5 billion to widen I-5, but misses the real bottleneck. The Marshall report uses detailed traffic speed data to pinpoint the actual locations of slowdowns, and identify the freeway segments that are producing congestion. The startling conclusion is that I-5 traffic is actually backed up because of capacity constraints outside the IBR project area, that won’t be fixed. In the morning, traffic backs up from N. Lombard Street (while moving rapidly on the I-5 bridge). In the afternoon, traffic backs up from N. Victory Boulevard

According to Marshall’s detailed analysis, widening I-5 at the Columbia River, as the IBR proposes will actually make traffic problems worse, especially in the morning peak hour, by funneling more traffic into these bottlenecks. The limited 3 lanes of I-5 in each direction between the Fremont Bridge and Lombard will continue to cause daily congestion. Marshall also points out that the project’s elaborate “heat maps” are a classic example of “garbage-in, garbage-out” because they rely on the unrealistic and biased “static traffic assignment” model which fails to accurately capture how bottlenecks work. This flawed traffic modeling means that the justification for the $7.5 billion is missing, that its environmental claims are wrong, and that its financial foundations are suspect.

Moving the goalposts: The Interstate Bridge Project has re-written the definition of “congestion” to try to sell its $7.5 billion freeway widening plan. For decades, Oregon DOT has defined traffic congestion as freeway speeds below 35 MPH. Now, for the Interstate Bridge project, IBR has moved the goalposts: now any speed under 45 MPH is counted as “congested.”

The definition of “congested” matters because its central to claims that in the future there will be more “hours of congestion” than there are today. But by changing the yardstick to count traffic traveling at up to 45 miles per hour as “congested,” IBR has artificially inflated the problem. The determination is based on an unpublished, incomplete ODOT study that was supposed to be finished a year ago. The new 45 MPH threshold contradicts WSDOT research showing freeways like I-5 maximize vehicle flow at 38.5 to 47 MPH. This is the kind of Orwellian tactic used by the highway lobby to justify ineffective and environmentally devastating boondoggles.

Must Read

The mythical claim that most Americans are living “paycheck to paycheck.” A favorite talking point and social media theme is claiming most American’s are barely getting by. Writing at SlowBoring.com Ben Krauss, takes a close look at the Lending Club survey claiming 60 percent of Americans say they live paycheck to paycheck. It turns out the survey is highly subjective, and as a result, nearly impossible to interpret, or square with other data: As xx points out:.

The first red flag is that the survey lacks a standardized definition of “living paycheck to paycheck.” Since the data is entirely self-reported, it relies on personal interpretation rather than objective financial metrics, making it less reliable than concrete measures of financial well-being like the poverty rate.

Those who have asked about the definitions and survey wording have been told that information is proprietary–something that hardly inspires confidence in the meaning or replicability of the results. For some, living “paycheck to paycheck” may be coincident with poverty, but for others, it simply means that their paycheck is getting spent on everything from groceries to mortgage payments to vacations to investment accounts. There is, of course, real economic hardship, but for most Americans incomes are up, and have risen faster than living costs. We shouldn’t be elevating a questionable and secretive click-bait survey result above actual economic data.

A Better Way to Build Downtown. Japanophile (and urbanophile) Noah Smith has a well illustrated commentary arguing for more dense and vibrant urban commercial areas as a way to revitalize our downtowns. He points to Japan’s Zakkyos—multi-story, street-facing commercial buildings that host a wide variety of shops and services, mostly provided by very small scale firms. Urbanists regularly praise “mixed use development” but Smith argues that Zakkyo buildings goes a step further to create dense concentrations of consumer choice.

Japan does things a bit differently from most of the world’s large, dense cities. . . . Shop-top development, which is common in dense cities all over the world, puts apartment buildings on top of restaurants and stores. Zakkyo buildings, which are a kind of development seen mostly in Japan, have stores on all the floors. My argument, basically, is that zakkyo buildings are at least partly responsible for many of the features that make Japanese cities such a consumer paradise

Mixing lots of commercial choices with dense urban housing maximizes the convenience, variety and discovery advantages that underpin great urban living. The long-time American zoning fetish of widely separated uses (and catering to car-scaled development) has made it impossible to get this kind of rich density. It’s time to revisit these assumptions.

Another explanation of Induced Travel: For those who need one. The most well documented by routinely ignored fact of urban transportation is the problem of induced travel. Building additional highway lanes in dense urban areas doesn’t reduce congestion: it triggers additional travel. The science is now clear enough as to be called the “fundamental law of road congestion.” But this reality is ignored or denied by road builders, who always assert that “one more lane” will fix traffic.

As if we needed more evidence on induced travel, Yale’s Climate Connections has a great explanatory interview with UCLA researcher Amy Lee. She boils the induced travel phenomenon down to simple economic terms:

. . . the biggest factor that people consider when deciding how to get around is cost. That’s a matter of dollars, but also time – time is a really, really important factor in how we travel. When a particular roadway is congested, traveling on it can take a long time, or an unpredictable amount of time, which discourages people from using it.

Highway widening is kind of like putting travel on sale. It attempts to reduce congestion by expanding the amount of roadway supply, reducing the time cost of travel for travelers using it. So let’s say traffic kept me from going to a restaurant I really like that’s 20 miles away, but after the highway is widened, I can go there more frequently. Or I might choose a doctor in the next town over as opposed to the one in my neighborhood.

We rearrange our travel patterns because of highway expansions, and the new driving that results is what we call induced travel. And research has shown that because of induced travel, congestion returns to previous levels about five to 10 years after the highway is widened.

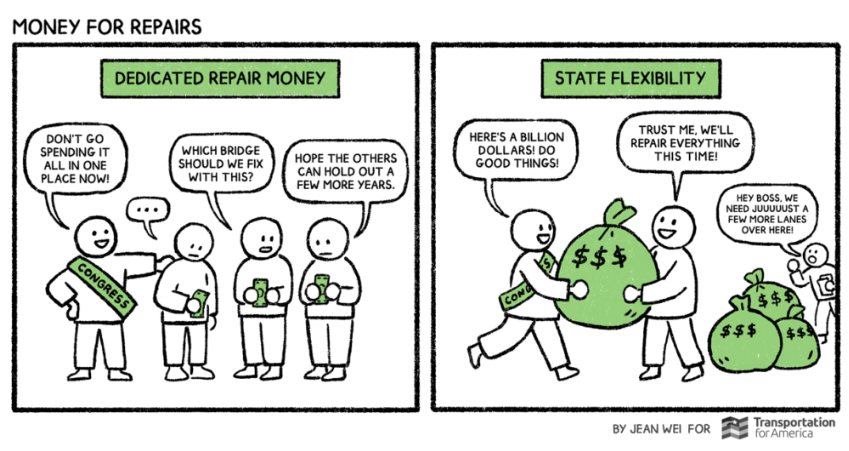

Time for a federal, “fix it first” mandate. One of the long-running cons in the highway world is the maintenance backlog “bait and switch.” Highway departments persistently plead pothole poverty, saying they need billions to repair or simply maintain deteriorating roads and bridges. But anytime they’re given additional funds, they get plowed into massive highway expansion projects–doing nothing to erase the backlog, and actually making it worse.

Transportation for America says its time for the US Department of Transportation to act like the adult in the room: essentially requiring states to maintain and repair what they’ve already got before they get additional funds for new capacity. Ironically, this is almost exactly what bond markets require before they’ll lend money for toll roads or bridges: the sponsoring agency has to show that they have an iron-clad financial plan for keeping the facility in tip-top shape. Federal funds ought not go to the grasping wastrels in state highway departments who’ve long treated basic maintenance as a fund-raising gimmick, rather than a fundamental responsibility.

In the News

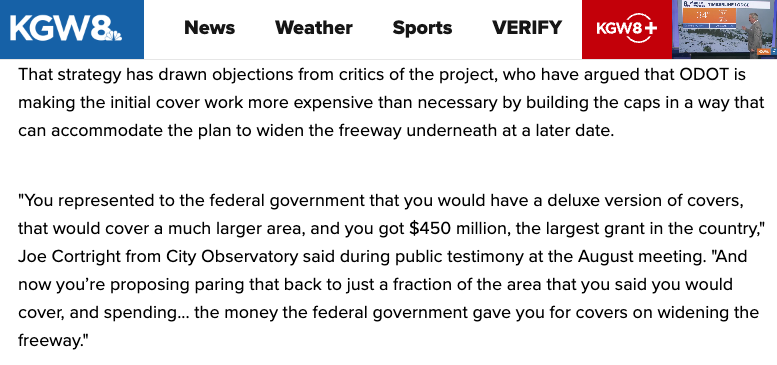

The Portland Mercury quoted Joe Cortright in its coverage of the denial of funding for the Rose Quarter project.

KGW-Television cited City Observatory’s Joe Cortright in its article on the federal government’s decision not to approve a requested $750 million grant for the I-5 Rose Quarter freeway widening project.