What City Observatory Did This Week

The Oregon Department of Transportation can and should mitigate the negative impacts of its highway construction projects, including social and economic impacts. ODOT’s massive $1.9 billion I-5 Rose Quarter highway project is billed as “restorative justice” because it would construct caps over the freeway that decimated Portland’s historically Black Albina neighborhood.

But what ODOT doesn’t acknowledge is that they are doubling the width of the freeway, which will worsen the damage, and that the project’s budget does nothing to repair the damage done to the neighborhood, especially the destruction of hundreds of homes—which ODOT has done nothing to replace. The agency claims it can’t spend highway money remediating these harms, but federal laws and policies actually authorize and require ODOT to fix the effects of its past discriminatory practices. We detail how four different federal laws and policies—NEPA, Environmental Justice, Civil Rights, and Reconnecting Communities—not only allow ODOT to spend highway money to fix these problems, but actually legally require it to do so.

Must Read

Declining rents in many US metro areas. ApartmentList.com is one of the nation’s keenest analysts of local rent trends, and they have a National Rent Report for April that shows rents declining, year-over-year in most large US metro areas. After the post-pandemic rent surge of 2021, investors poured billions into building new apartments, and those are now coming on line, helping to push down rents. Nationally, rents are down about 0.8 percent compared to a year ago.

There are, of course, wide variations by market. Rents have been cool in the Sunbelt and the west, but are continuing to increase in the Northeast and Midwest.

As widely noted, a flood of new apartment construction in Austin has turned around that once hot market, which has seen a decline in rents of 7.4 percent in the last twelve months.

Austin’s MPO waves on a massive freeway project. Freeway fighters in Austin mobilized to challenge the proposed multi-billion dollar widening of I-35 through the city at CAMPO, the region’s Metropolitan Planning Organization, which under federal law has to bless transportation projects supported with federal funds.

Even though nearly all of the City representatives voted to subject the plan to an air quality review before proceeding, they were handily out-voted by the suburban dominated membership of CAMPO. Even though Austin represents nearly half of the region’s population, it has just four of 22 votes on CAMPO. It’s plainly undemocratic, but unfortunately the highway lobby prevails with the same shopworn arguments even when regional MPO’s are directly elected on a one-person, one-vote basis, as in Portland.

Jane Jacobs: Urbanist, Cyclist. Jane Jacobs is justly famous as one of the most incisive analysts and advocates for cities. What’s perhaps less known, and especially interesting in light of today’s urbanist discussions, is that Jacobs, who never learned to drive, regularly rode her Raleigh around New York City.

Writing in Common Edge, Peter Laurance profiles Jacobs in the saddle, traversing New York, fighting Robert Moses, and being among the first to decry the automobiles toxic effects on urban living. Jacob’s children described her as an avid cyclist, who traveled by bike to her honeymoon, and on vacation:

Cycling holidays later continued with their children who rode, Dutch-style, on the back of Jane’s and Bob’s bikes when they were still too young to keep up on their own wheels. In the 1950s, the family would escape the August heat of the city on bikes, cycling to Grand Central Station, loading their bikes for Cape Cod, then the ferry to Nantucket.

While she coined “sidewalk ballet” to describe the essential role of walking in cities, her own life has a lot to say about how integral bikes are to urban quality of life. It’s a helpful reminder as some try to pit walking against biking as an organizing principal for cities that Jacobs supported—and practiced—both.

New Knowledge

The demise of the “spatial mismatch” hypothesis? One of the most enduring theories for the persistence of Black-White economic gaps in the U.S. is the “spatial mismatch” hypothesis: the idea that for Black workers and households tend to live further away from jobs, and growing job centers, and that this lack of proximity disadvantages them in getting employment and earning higher incomes. The hypothesis was advanced by economist John Kain in the 1960s, who observed the growing suburbanization of employment opportunities in the US coupled with historic patterns of segregation that left a disproportionate share of Black households living in central cities, far away from newly created jobs.

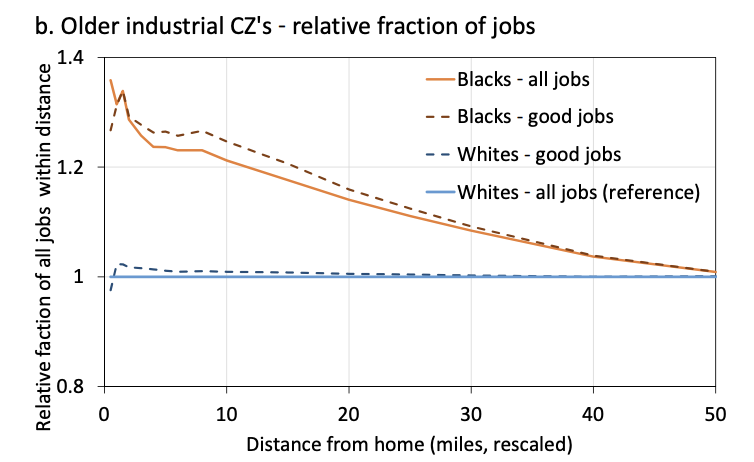

A new paper from David Card, Jesse Rothstein and Moises Yi uses data from the Census Bureau’s Local Employment and Household Dynamics (LEHD) data series to look at variations in wage earnings for black and white workers and their proximity to employment opportunities. The analysis challenges some of the key assumptions underlying the Spatial Mismatch hypothesis, key among them that Black workers are further from jobs. The data show, on average Black workers live closer to jobs, including to good-paying jobs.

This chart shows that Black workers have about 20 percent more jobs within ten miles of their homes than do white workers. These data are for older industrial metro areas; the same pattern holds to a lesser degree for Sunbelt metro areas. The data also show that Black workers have, on average, shorter commutes to work.

Looking at wage differences between Black and White workers, the author’s don’t find any significant effect due to spatial mismatch:

Our findings suggest that geographic proximity to jobs – or to “good” jobs as measured by their AKM pay premiums – is not a major source of racial wage gaps in large cities in the U.S. today. At the most basic level, we find no evidence that Black workers are systematically under‐represented at workplaces with above‐average pay premiums. Paralleling results that have been obtained in many earlier studies, we also find that Black workers live, if anything, closer to places where existing jobs are located. Importantly, this relative proximity for Black workers extends to “good jobs.”

David Card, Jesse Rothstein, & Moises Yi, Re-Assessing the Spatial Mismatch Hypothesis. March 2024. NBER Working Paper 32252 http://www.nber.org/papers/w32252