What City Observatory Did This Week

Unique Local Experiences: The Hidden Value in Urban Economies. An often-overlooked aspect of urban economics: the value of unique, local, and seasonal experiences. We take as an example the case of Hood strawberries in Oregon’s Willamette Valley, we explore how scarcity and locality can enhance economic and cultural value in cities.

- Localized products: Hood strawberries, available for only three weeks annually near Portland, exemplify how geography and seasonality create distinct local offerings.

- Quality over standardization: Unlike mass-produced varieties, Hood strawberries prioritize flavor and quality over shelf-stability, highlighting a consumer preference for authenticity.

- Economic differentiation: These unique products contribute to a city’s distinct identity, potentially boosting local economies through tourism and specialized markets.

- Consumer behavior: Economist Paul Krugman notes that scarcity can increase perceived value, challenging traditional economic models of consumer choice.

- Urban diversity: Jane Jacobs’ assertion that a city’s greatest asset is its uniqueness is supported by the enduring appeal of local specialties.

Other data shows consumers increasingly prefer local restaurants to national chains, suggesting a growing market for unique, place-based experiences. This trend could inform urban planning and economic development strategies, emphasizing the cultivation of distinct local offerings to enhance city competitiveness and resident satisfaction.

Must Read

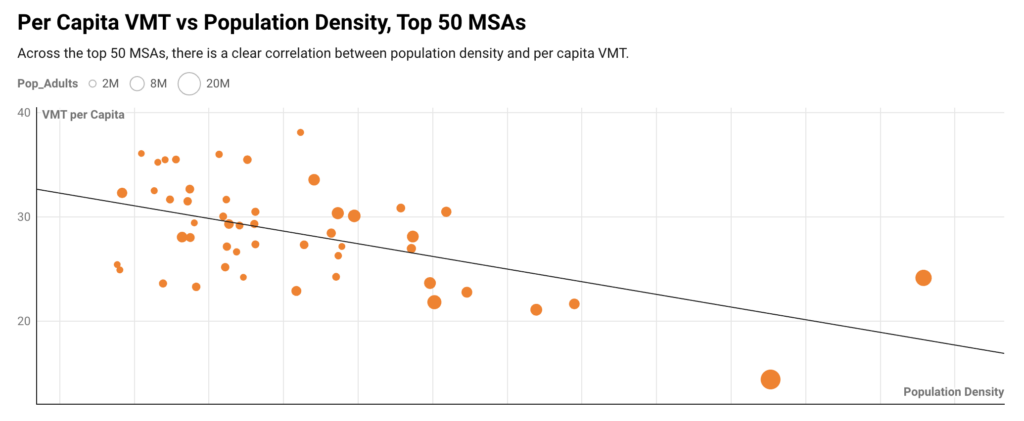

Where do people drive most? Replica, a firm that uses mobile phone location data to plot travel patterns, has produced estimates of the number of vehicle miles traveled by the average person each of the nation’s 50 largest metropolitan areas. The results show which places are most car-dependent (and who consequently spend the most of transportation, and produce the most pollution.

According to Replica, New York is far and away the least car dependent Metro area, with average daily VMT of fewer than 15 miles per day. At the other end of the spectrum, sprawling Raleigh, Birmingham, Jacksonville and Nashville drive more than twice as much, on average (over 35 miles daily).

A key factor in explaining which places drive the most is urban density. The least dense places have the greatest amount of driving; the most dense places have the least driving.

Kudos to Replica for providing this detailed data with which to compare metro areas on this key metric, and to better understand the factors, like urban density, which determine patterns of driving.

Crime is declining. Noah Smith has a review of a wide range of data that all point in the same direction: Despite political rhetoric to the contrary, crime in the US is declining. The numbers from FBI all point tin the same direction fro almost every kind of crime (motor vehicle theft being the sole exception.

As Smith points out, the FBI data is confirmed independently by several other sources.

So we have six data sources, using six different methodologies, all telling us the same story about crime: the FBI, AH Datalytics, the Council on Criminal Justice, the Major Cities Chiefs Association, the Gun Violence Association, and the Center for Disease Control. All of them agree that murder peaked in 2021, and those that report other types of violent crimes agree that they also peaked in 2021.

The are many theories behind the increase (and now decrease) in crime rates in the past few years. But the data clearly show that crime is now far lower than it was twenty or thirty years ago, and that despite an uptick in 2021, is clearly coing down.

Humans are poorly equipped to make good decisions about climate related issues. Research published in Nature Climate Change shows that most of us lack a good understanding of how different actions influence climate change. Climate change is complex, and we as humans tend to lack the detailed information to discern what is sustainable from what isn’t, and in addition we lack the cognitive skills to make sense of the problem. These information and thinking problems cause us to mis-estimate which actions will be effective, whether we’re taling about personal consumption, investments or public policy.

To economists, this is a key reason why carbon pricing is essential: consumers lack the time and inclination to deal with the cognitive burden of assessing which choice is greenest. They are very capable, adept and motivated to compare and react to prices. Even when they are well motivated, and well-intended most of us will never have the information or skill to optimize our carbon footprint. A set of prices that automatically and universally reflected back to everyone the consequences of their actions would lighted the load, and prompt much greater and more effective adaptation.