What City Observatory Did This Week

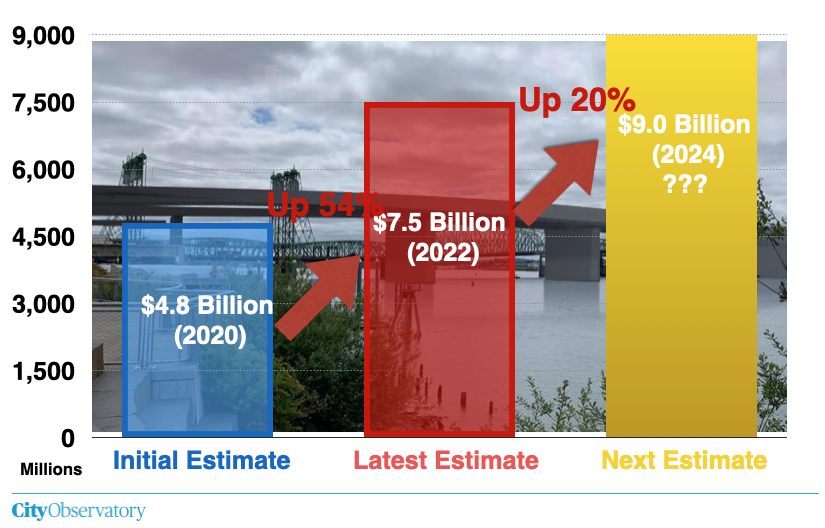

The cost of the Interstate Bridge Replacement (IBR) is going up: But we won’t tell you how much . . . And we’re not going to tell you until a year from now, after the 2025 Legislature adjourns

In January, 2024, IBR official publicly acknowledged that their 13 month-old cost estimate of up to $7.5 billion was wrong, and promised a new estimate “later this summer.”

It’s now summer, and IBR officials are now saying their new estimate won’t be done for another year— “about this time next year” (meaning June 2025).

IBR officials are keeping secret the new higher cost until after the Oregon and Washington Legislatures meet. ODOT has specifically excluded any mention of additional funding for the IBR project from its presentations to legislative committees contemplating a new finance plan for ODOT for the 2025 session.

ODOT is touting a newly announced $1.5 billion federal grant for the project. But the project’s price tag is rising faster than it is finding money to pay for the bridge. And Oregon and Washington will be holding the bag for any cost increases or toll revenues shortfalls.

Must Read

Harris on transportation and climate. As California Attorney General, Kamala Harris sued San Diego’s regional planning agency over the climate effects of its highway-oriented regional transportation plan. California’s state level environmental disclosure law—CEQA—requires an analysis of the environmental impacts of major public policies, including San Diego’s long range transportation plan. In 2012, Harris pushed for greater emphasis on reducing pollution and promoting transit, rather than widening highways. Her office reported that

The lawsuit contends that the Environmental Impact Report (EIR) prepared for the plan does not adequately address air pollution and climate concerns and prioritizes expanding freeways while delaying public transit projects.

Then-Attorney General Harris is quoted as saying:

“The 3.2 million residents of the San Diego region already suffer from the seventh worst ozone pollution in the country. Spending our transit dollars in the right way today will improve the economy, create sustainable jobs and ensure that future generations do not continue to suffer from heavily polluted air.”

Oregon spends its climate dollars subsidizing car travel. Bike Portland has a keen analysis of a $197 million federal climate grant awarded to Oregon. All of the $66 million devoted to reducing transportation emissions goes to subsidizing cars and none of it goes to promoting biking, walking or transit or reducing vehicle miles traveled. As Bike Portland notes:

I was surprised to see that all the funds awarded to Oregon will be spent on cars. Regardless of how they are powered, state subsidies for cars will increase vehicle miles traveled (VMT), lock more Oregonians into lopsided financial relationships with banks and major corporations who benefit from people who use the most expensive transportation option available, cause more deaths and injuries on our roads, create more traffic bottlenecks, clog neighborhoods with parked cars, and perpetuate highway building and expansions.

Just last year, the Oregon Department of Transportation issued a report saying the state should make it easier for people to buy e-bikes; but then given a sizable federal grant it spent exactly nothing on this climate strategy.

The high cost of inclusionary housing requirements. Sightline’s Dan Bertholet identifies five fatal flaws that could make inclusionary housing mandates for transit-oriented development a net detriment to housing affordability. Washington State has been considering legislation to allow more housing to be built in transit-served areas, but politically it has been paired with an inclusionary housing requirement that subverts the purpose of the law:

The inherent problem with unfunded IZ is that its cost impedes the production of housing. It’s a preventative tax on housing when what we need for affordability is far more housing. Sometimes, when market conditions are just right, that tradeoff can be worth it—if it yields some affordable homes and doesn’t reduce the overall supply by much. But in many cases, IZ backfires entirely, thwarting the construction of both market-rate homes and income-restricted homes.

And even seemingly modest inclusionary requirements have profoundly negative effects on housing production and affordability. Bertholet points to a study of Los Angeles which shows

For every below-market rate home gained through IZ, 4.5 market-rate homes are lost. In other words, creating 1 affordable home through IZ makes the housing shortage 4.5 homes worse than it would have been without IZ.

The political case for inclusionary zoning rests on the idea that one can tax or punish developers and somehow extract funds from them to pay for affordable housing. By design, nearly all “inclusionary” requirements are un-funded, and even when partially funded, encumber housing development with additional burdens that reduce housing supply and drive up rental prices.

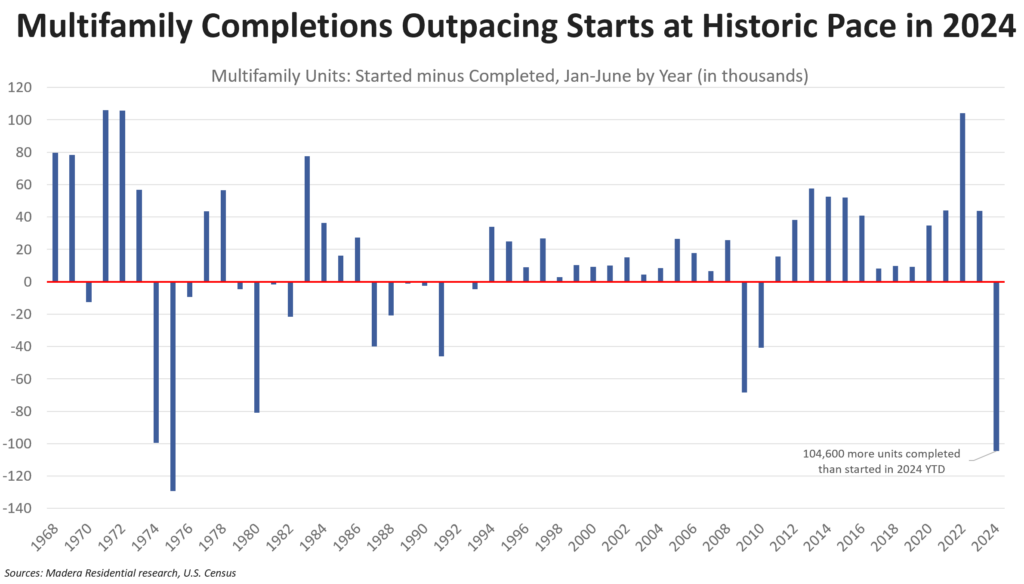

The scary decline of the apartment pipeline. The good news for housing affordability for the past year or so has been a strong growth in the number of new apartments coming on to the market, blunting rent increases and leading to actual declines in many markets, such as Austin. But real estate markets operate with a significant lag: it takes usually a couple of years (and much longer in some cities) between the time a developer seeks permission to build and the time new apartments are leased. And as Jay Parsons points out, thats what makes a look down the pipeline rather ominous.

The excess of of apartment completions over new starts reached more than 100,000 in the first half of 2024, the highest gap in half a century. This almost certainly foretells a big slowdown in apartment growth in the years ahead, and that constrained supply is likely to lead to rental increases in the years ahead.

In the News

StreetsblogUSA quoted Joe Cortright’s comment “Let them drive Tesla’s is not a climate policy” as advice to Vice-President Kamala Harris.