Must Read

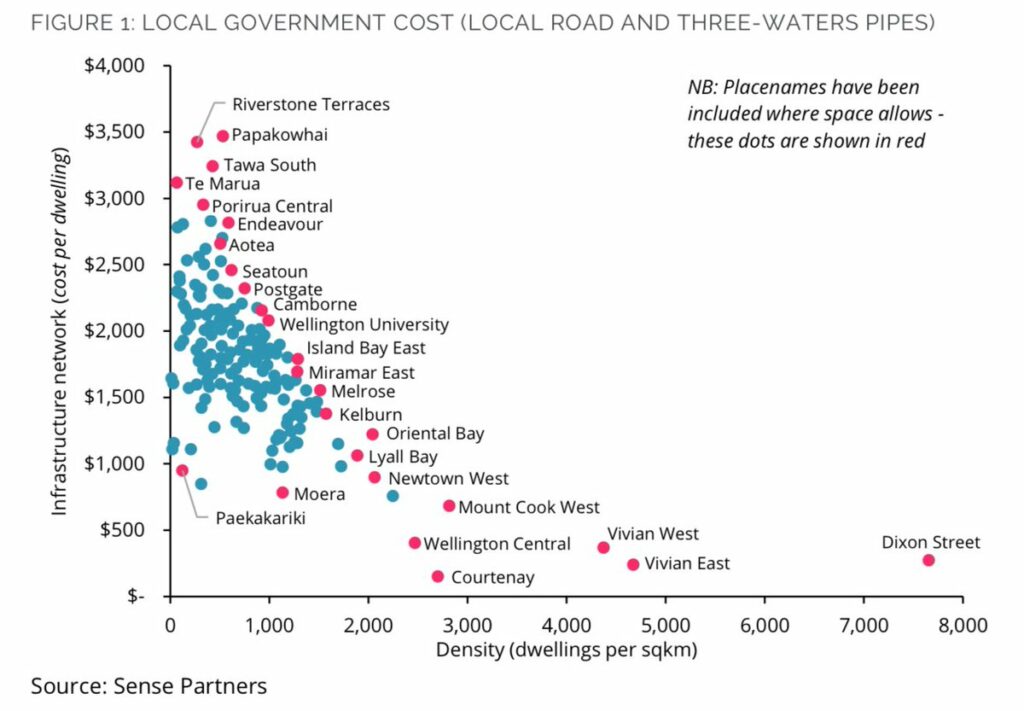

Denser cities = Less expensive infrastructure. A new study from New Zealand confirms one of the fundamental intuitions about cities: Places with higher levels of residential density have lower per capita and per dwelling costs of providing physical infrastructure. This study looked at the cost of providing roads, water lines and sewers to different neighborhoods in Wellington, and found a strong negative correlation between density and infrastructure cost: The denser the neighborhood the lower the cost of providing roads, sewers and water.

Local officials pointed out that its far more fiscally prudent to focus growth in more central locations:

The further out we go, the further we have to pave roads and lay pipes, and the greater the cost to local councils, the government, ratepayers and taxpayers both now and especially in the future. . . . We can achieve greater value for money for our infrastructure investment by prioritising public transport spending that supports compact, high-amenity urban growth . . .]

Cities are a more efficient and affordable way of providing places for people to live. If we want to reduce the cost of living–and the cost of public services–we should be promoting greater density, not sprawl.

The slow death of outdoor dining? One of the most dramatic (and rapid) changes induced by the pandemic was the conversion of street space to meeting- and eating places. Cities around the country allowed restaurants to convert a portion of the street in front of their businesses into covered service areas. Overnight, we simply chose to shift the use of public space from storing private automobiles to encouraging public interaction. It was a flowering of “third places.” But now that’s being unwound. In New York, the city has begun imposing rules that make it expensive or impossible for businesses to maintain street eateries. Streetsblog New York reports that only about two dozen businesses appear to be moving forward to get the necessary permits to maintain their street dining options:

New York City is likely to see a steep drop in restaurants offering outdoor dining in roadways after its permanent al fresco program phases out the pandemic-era structures next month — with less than two dozen restaurants, cafes or bars currently lined up to get roadside “streeteries” approved by the Department of Transportation.

The Covid Pandemic taught us that many of the habits and conventions of the past could be quickly changed, often for the better. It would be a shame if we un-learned the insights about how we could make better use of our streets.

A profound failure to under-estimate “full employment.” Adam Ozimek has a commentary (on X-twitter) pointing out that the economics profession, as a whole, substantially under-estimated what constituted “full employment.” In the wake of the Great Recession, economists adopted a view that the overall US economy couldn’t grow very much or very fast due to permanent changes in the labor market. This “soft bigotry of low expectations” led them to under-estimate how much we could grow, with the result that millions were left unemployed or underemployed, as we failed to grow the economy as much as we might. The practical experience of the fiscal stimulus in the wake of the Covid pandemic showed that the standard economist’s view of growth potential was understated, that that we could employ many more people–and pay them higher wages. As Ozimek writes: