What City Observatory Did this Week

Is it time to address the problem of “Missing Massive” housing? This past week marked the latest convening of YIMBYTown, this year, held in Austin, Texas. One of the perennial topics was state strategies to promote “missing middle” housing—as evidenced by multiple initiatives to allow duplexes, triplexes and four-plexes in what have been exclusively single family zones. There’s real merit to missing middle reform, but the housing supply and affordability problem likely requires a much larger scale solution. Alex Armlovich coined the term “Missing Massive” to highlight the need to build taller and denser in those transit-served, amenity-rich, opportunity-proximate places where demand supports more housing. As we’ve pointed out at City Observatory, by definition, taller, higher density buildings require that less land be redeveloped to produce any given number of new housing units.

“Missing middle” is a good place to start, and is a great way to add some density, and improve the range of housing choices in many neighborhoods. But it we’re really going to tackle the housing affordability problem at scale, it will likely require some discontinuous leaps forward in key locations. Housing policy should fill the voids for both missing middle and missing massive housing.

Must Read

“Safe systems” is being sabotaged. This is a must, must read. Kea Wilson, writing at Streetsblog, steps back from day-to-day reporting to offer a powerful perspective on ways in which the “safe systems” approach to road safety is being diluted and distorted by the dominant paradigm of car-centric planning. In principle, safe systems is a well-ordered set of priorities for changing how we approach the construction and management of roads. In practice, most state transportation departments and their local partners mouth the words, but haven’t changed their policies or investments.

And, as Wilson points out, the rhetoric of safe streets is being appropriated and bastardized. Just as the term “multi-modal” is glibly used by highway departments to greenwash a multi-billion dollar highway widening project that includes a token pedestrian path, the term “shared responsibility” is used to evade responsibility.

The trouble with “shared responsibility,” of course, is that it says nothing about our respective ability to save lives — or how that “responsibility” should be shared relative to our respective power and influence.

Highway agencies still overwhelmingly treat safety as an “education” or “awareness” challenge, to be treated with feeble and often insulting, victim-blaming advertising and slogans. And meanwhile, the real resources flow to making cars move faster, not making roads safer. As Wilson argues:

It’s great — if painfully overdue — that America has finally realized that traffic violence is a systemic problem with systemic solutions. If we can’t advance the conversation beyond that astonishingly low bar, though, the Safe Systems approach will become just another way for powerful people to keep passing the buck to the “safe road users” piece of the puzzle — and the powerless will keep unsuccessfully shouldering the weight of a “responsibility” that they never had any hope of carrying in the first place.

If you want to move the safety conversation forward, please read Kea Wilson’s excellent essay.

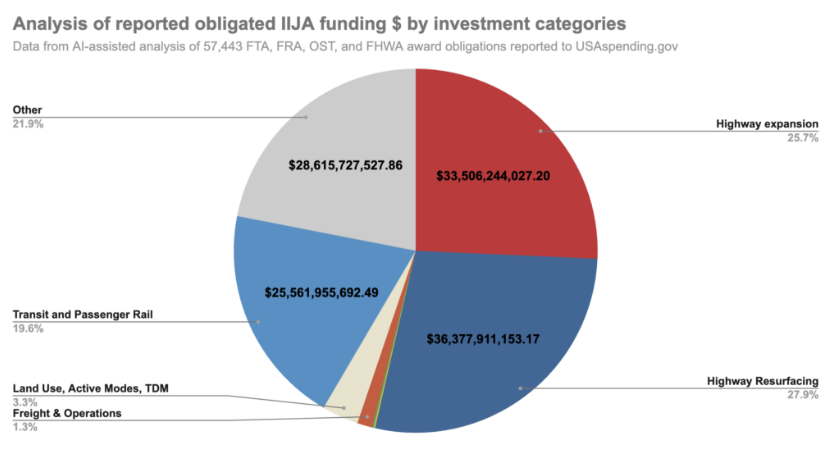

How the infrastructure bill is aggravating climate change. The Infrastructure Investment and Jobs Act (aka the Bipartisan Infrastructure Law) represented a major federal commitment to boost the nation’s capital spending. The law talked about opportunities to use these funds to help deal with pressing problems like climate change, but have left actual decisions about where to spend the money largely up to the states. A new analysis from Transportation for America shows that a huge share of these funds have been plowed into subsidizing highway expansion projects.

Transportation for America reports:

Instead of using the historic funding levels to give people alternatives to congestion, pollution, and car dependency, our analysis finds that states have designated over $33 billion in federal dollars (over 25 percent of analyzed funds) toward projects that expand road capacity, doubling down on a strategy that has failed time and time again.

This problem is compounded by a relatively slow roll out of spending for transit, compared to a very aggressive rate of spending on road projects: about 64 percent of highway formula funds have already been allocated by states, while only 20 percent of transit funds have gone out. Vesting discretion on how to spend infrastructure funds with agencies that are either in denial about climate change, or unwilling to even measure and report their carbon footprint, has produced predictable results: more subsidies to driving that will only lead to more traffic, more congestion, and more greenhouse gas emissions.

State land use reform as a critical climate strategy. Climate change strategies lean heavily on the “technical fix”—the idea that new technologies will eliminate the need for any of us to live our lives any differently. A new report from the Rocky Mountain Institute argues that changing state land use policies can contribute both to achieving greenhouse gas reductions, and addressing fundamental issues of housing affordability and equity.

RMI analysis shows enacting state-level land use reform to encourage compact development can reduce annual US pollution by 70 million tons of carbon dioxide equivalent in 2033. This projection, based on 2023 data, underscores the potential for significant impact within a decade. It would deliver more climate impact than half the country adopting California’s ambitious commitment to 100% zero-emission passenger vehicle sales by 2035.

The key policies that would support compact development hinge on more housing in places where it is easier to live without a car. RMI calls for ending exclusionary zoning; deregulating and pricing parking; eliminating minimum lot sizes, unit sizes, and setback requirements; legalizing accessory dwelling units (ADUs); and building permitting reform. Housing in dense neighborhoods addresses the affordability problem in two ways: it tends to drive down rents, and also lowers the amount residents have to spend on cars and gasoline to meet basic transport needs. As RMI says, reforming land use to encourage more compact development is a win-win for affordability and climate.

Anti-trust law and local food access. The Federal Trade Commission has come out in opposition to the proposed merger of two of the nation’s largest grocers, Kroger and Albertsons. As NPR reports, the FTC is concerned the merger would be bad for consumers and workers, increasing the market power of the combined company to set prices and limit wage growth. But there’s another wrinkle as well: the two chains have overlapping stores—some across the street from one another—in many metro areas. The merged company plans to achieve “efficiencies” by consolidating stores in these markets, which means less choice and less accessibility to consumers.

In all, Kroger and Albertson’s have said they will sell off 650 stores to other chains, but its far from clear how viable those spun-off stores will be in the long term. After an earlier merger with Safeway, Albertsons sold off a bunch of stores to competitors who weren’t economically viable, and ended up buying many of them back. Anything that reduces the total number of grocery stores, and lessens competition in this sector, is likely to affect consumers, who will have to travel further, and have fewer choices.