What City Observatory did this week

Thirty seconds over Portland: Spending $7.5 billion on a freeway widening project will save the typical affected commuter about 30 seconds a day, according to the Interstate Bridge Replacement Project’s yet-to-be-released Environmental Impact Statement. IBR officials have said they fear leaks of the EIS could create a negative perception of the project, and this is one of several likely reasons for their fear.

Oregon and Washington DOTs claim that a massively widening I-5 bridge and approaches is needed to fight congestion between Portland and Vancouver—but their own traffic modeling shows the project will make almost no difference in average commute times. The EIS claims that average traffic speeds in the project area will increase from 33.0 miles per hour in the “No-Build” scenario, to 33.4 miles per hour in the build scenario. For a typical commute of 7.1 miles, that works out to a daily savings of 30 seconds per day. Is that worth $7.5 billion?

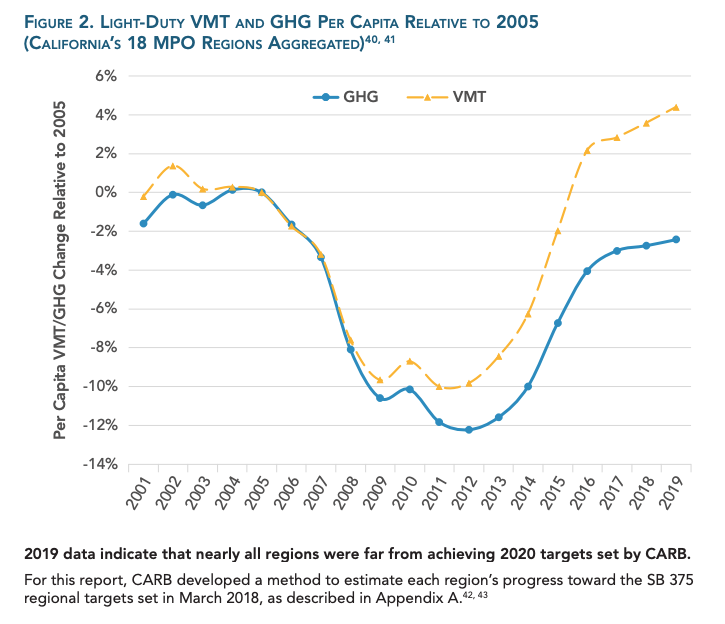

The importance of honest accounting for transportation greenhouse gases. You can’t tell if you’re winning or losing if you don’t keep score, especially when it comes to transportation greenhouse gas emissions.

But a close look at the data shows we’re not making much progress, and not making it fast enough, primarily because we’re driving more. Your state highway department is likely to be in denial about these facts, and doing its best to hide them from the public. California is ahead of most states in thinking hard about how to tackle climate change. Its report reveals that the state made good progress for a decade, but since then has backslid, principally because of an increase in driving after oil prices collapsed in 2014.

Bloviating about tactics, and simply repeating future goals, is no substitute for frank reporting of current GHG levels: Is your state accurately reporting current transportation greenhouse gas emissions?

Must Read

The routine and regular deaths of thousands on the nation’s streets and roads are evidence of deep dysfunction in the traffic engineering profession. As illustrated by the recent and prompt responses to airline safety concerns and a ship-hitting-the-span in Baltimore, some disasters provoke a quick and effective reaction. Meanwhile, the far more common, and by any measure much more grievous daily slaughter on our roads is acknowledged, but then largely accepted, if not ignored. Isabella Chu has a powerful indictment of this malaise in her guest commentary at Streetsblog.

The thing that causes death and injuries on American roads is cars. The way to reduce deaths and injuries is to reduce the dose of the hazard: cars. That means slower, smaller, and fewer cars. It means investing in meaningful alternatives to driving and making it possible to walk and take transit places without dealing with continual delay, noise, exhaust, and risk of blunt force trauma from cars. It means affording people outside of cars full personhood and treating their mobility and lives as more important than the convenience and property of motorists.

Where’s the fire? How fire departments are undermining affordable, safe, livable cities. Brad Hargreaves has a far reaching, well-researched and compelling analysis of how the myopia of the firefighting profession is colliding with efforts to promote road safety, increase affordable housing, and ease walkability. He argues:

For all the good they do, fire departments have increasingly emerged as a primary force preventing cities from embracing walkability, safer streets, transit, and affordable housing.

Historically, fire was one of the chief threats to life in cities, and indeed fires wiped out vast swaths of cities (as in the Great Chicago Fire and the San Francisco Earthquake and Fire). Fire departments are deeply entrenched institutions with a particular worldview. But actual fire-fighting is a vanishingly small part of what they do. Fires represent about 4 percent of fire dispatches, car crashes make up almost half-again as many dispatches. And crashes kill ten times a many Americans as structure fires.

But those shifting challenges have done little to change the worldview of firefighters, who cling to a narrow notion that promoting safety requires cities to be engineered to get big firetrucks quickly to structure fires. Consequently, fire departments oppose many traffic calming measures, like roundabouts and road diets, which are proven to save lives by lowering speeds and lessening the probability and severity of crashes. And fire departments play a key role in housing policies, frequently oppose key measures, like liberalizing “single stair” construction in 3-to-6 story multi-family housing—which would make housing much more affordable. As Hargreaves points out:

. . . only 12% of all fire deaths—470 in 2022—occurred in apartments. When apartments do catch on fire, their occupants are more likely to survive than those in single family homes, as apartments are more likely to have interventions like sprinklers, non-combustible materials, and working fire alarms.

Fire departments have broadened their mandate to “emergency services,” but despite a long tradition of thinking about prevention as part of their responsibility when it comes to structure fires, they haven’t applied this same thinking to what is now the largest threat to life and limb in most American cities: the car dominated landscape and transportation system.

NIMBY’s for rent control. If you thought that historic preservation was the latest clever subterfuge for maintaining exclusionary zoning, time for an update. Californians may vote on a ballot measure that would give cities wide authority to mandate rent controls. While ostensibly a measure designed to help renters, at least one exclusionary suburb, Huntington Beach, has recognized that requiring strict rent controls on new multi-family housing would be an effective way to ban apartment construction—and evade state laws designed to expand housing supply. The city’s Republican Councilman Tony Strickland explained the strategy, as reported by Politico:

“Statewide rent control is a ludicrous idea, but the measure’s language goes further, . . It gives local governments ironclad protections from the state’s housing policy and therefore overreaching enforcement.”

Strickland said Weinstein’s rent control measure would block “the state’s ability to sue our city” because Huntington Beach could slap steep affordability requirements on new, multi-unit apartment projects that are now exempt from rent control.

In practice, the Jacobin rallying cry that all housing should be affordable housing simply means that no housing gets built at all, which is exactly what exclusionary suburbs want. It’s a classic instance of horseshoe politics: where NIMBYs of the left (seeking draconian rent control) and NIMBYs of the right, who simply want to exclude apartments, make common cause for a policy that restricts housing supply and aggravates affordability problems.