What City Observatory did this week

What if we regulated new car ownership the same way we do new housing? Getting a building permit for a new house is difficult, expensive, and in some places, simply impossible. In contrast, everywhere in the US, you can get a vehicle registration automatically, just for paying a prescribed fee. We make it really hard to build more homes, but very easy to buy more cars. Little wonder we have a housing shortage and massive unaffordability, and percieve chronic traffic congestion and parking shortages.

But it doesn’t have to be that way: A recent story about Singapore caught our eye: In Singapore, you can’t even buy a car without a government issued “certificate”—and the number of certificates is fixed city wide. The government auctions a fixed number of certificates each year, and the price has risen to more than $100,000. This means that a Toyota Camry, which costs about $30,000 in the US, would cost a Singapore buyer about six times as much (including all taxes and fees). Our housing and transportation problems are ones largely of our own making, reflecting the usually unexamined choices we’ve made about how we tax and regulate both.

Must Read

CalTrans whistleblower reveals highway widening bias. On the surface, California has bold policies that emphasize reducing vehicle miles traveled. But underneath the hood, the state’s DOT, CalTrans, is still a highway building and highway widening agency. Jeanie Ward-Waller, the agency’s deputy director for planning has been effectively fired, in retaliation, she argues, for calling out two deceptive and likely illegal steps the agency took to advance freeway widening projects that violate state and federal policies. Ward-Waller charges that CalTrans took money for “pavement restoration” and used it to pay for widening a stretch of Interstate 80, and also broke the project up into a series of smaller projects to avoid a close environmental review. These are tactics that other states have used as well, including Oregon. This is a particularly important case because it calls out the profound disparity between headline policies (we care about climate, and we’re going to reduce VMT), and actual bureaucratic performance (out of the limelight, we’ll divert funds and avoid environmental review, and keep widening highways the way we always have). Kudos to Ward -Waller for having the courage, at great personal expense, to call out this outrage.

California is spending precious little of its transportation budget on projects that reduce climate pollution. Hot on the heels of this whistleblower charge is a new report from the National Resources Defense Council taking a close look at how California spends its transportation dollars. Again, despite high-minded policy declarations about climate priorities, NRDC finds that less than 20 percent of state transportation spending goes to climate-friendly investments.

Our analysis finds that California state agencies have only allocated 18.6% of available funds towards projects and programs that are helping curb Californians’ reliance on private automobiles by investing in projects and programs like bike lanes, sidewalks, electric buses, mass transit, regional rail systems and affordable housing.

The remaining 81.4% is allocated respectively towards maintaining (71.7%) and expanding (9.7%) the current system of roads and highways that contribute not only to climate pollution, but also unhealthy air, urban sprawl and endemic traffic fatalities. NRDC’s number one recommendation, reads like the Hippocratic Oath: First, do no harm:

- Discontinue funding for projects that increase highway capacity and thus increase VMT and greenhouse gas emissions. Projects should be rescoped to achieve project goals in ways that align with the State’s climate goals.

New Knowledge

Single young adults fuel population growth in DC. The DC Policy Center has an interesting new report charting key population changes in Washington. In contrast the the simple (and largely wrong) “doom loop” narratives, about cities, this study shows that dense, amenity-rich urban locations are still a powerful attraction for well-educated young adults.

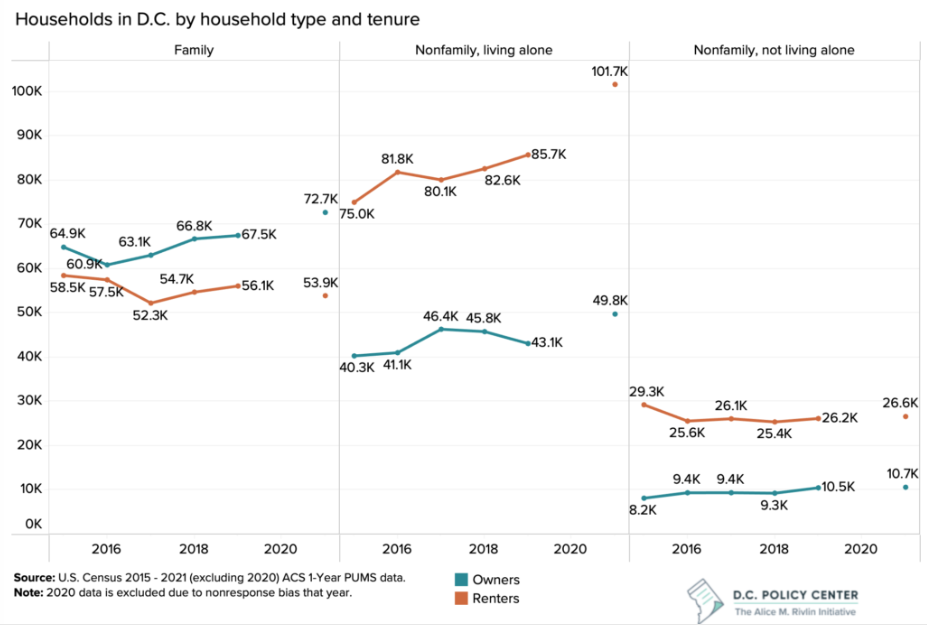

The top-line census numbers for the District of Columbia appear to support the urban-doom loop scenario: Between 2019 and 2022, DC’s population declined by 3,500 persons. But while overall population totals declined slightly, there was an increase in the number of households,

. . . the number of households increased by 9.6 percent (27,994). Despite the uptick in households, during this period, the District has lost population: the city’s estimated population for 2021 was 668,791, a 5 percent decline from 2019.

The growth in the number of housheholds was fueled by individuals living alone. These single-person households tended to be young, and renters compared to the overall population. As the report points out, while the number of multi-person households in the district was flat to slightly declining; there was a significant increase in the number of single person households. The most notable change was among nonfamily renters living alone; their number increased from about 75,000 in 2015 to more than 100,000 households in 2021.

What the report shows is the very nuanced picture of population change and housing markets in the District of Columbia. Dense, urban living is obviously very attractive to many well-educated, single young adults. This demographic can use their buying power to bid for apartments (indicated by the 25,000 household increase in renters living alone). In effect, DC residents are consuming more housing, per person, than they did just five years ago. This likely reflects a combination of rising incomes (among these residents), a growing demand for residential space (post-pandemic), and the continuing attraction of urban living.

The growing demand for urban living among younger, single person households also signals the challenge to housing markets. The number of households is increasing faster than the population. As a result, a city has to grow its housing stock just to make sure that its population doesn’t decline. As we noted a few weeks ago, careful studies of New York City show that the city lost tens of thousands of housing units due to the consolidation of smaller apartments into larger ones. In the face of growing demand for urban living, cities have to move even faster to expand housing if they want to avoid population loss, displacement and declining affordability.

Bailey McConnel and Yesim Sayin, D.C.’s household growth is predominantly driven by singles aged 25 to 34, DC Policy Center, October 3, 2023