What City Observatory did this week

5 million miles wide of the mark.Portland’s regional government Metro, has proposed a regional transportation plan (RTP) that purports to achieve state and regional policies to reduce greenhouse gas emissions. But there’s a 5 million mile problem: The climate analysis of the Metro RTP assumes that the region will hold driving at about its current level through 2045—about 20 million miles per day. But the region’s transportation modeling and performance measures–which drive project selection and budget decisions, have a very different future in mind, planning for a 20 percent increase in driving to 25 million miles per day. The plan can’t reconcile the 5 million mile a day discrepancy.

Metro’s Regional Transportation Plan (RTP) claims it will meet state and regional climate objectives by slashing vehicle travel more than 30 percent per person between now and 2045.

Meanwhile, its transportation plan actually calls for a decrease in average travel of less than 1 percent per person. Because population is expected to increase, so too will driving.

Rather than reducing driving, and associated greenhouse gas emissions, Metro’s RTP calls for accommodating more than 5 million additional miles of driving a day—a 20 percent increase from current levels.

The RTP climate strategy asserts the Portland area will drive 20 million miles a day and meet our greenhouse gas reduction goals. But Metro’s transportation modeling shows the RTP is planning for a system that will lead to 25 million miles per day of driving.

This disconnect between Metro’s climate modeling, and the modeling it’s using to size the transportation system, and make investments violates state climate rules.

Must Read

The devil is in the detail for congestion pricing. It looks increasingly likely that New York will actually implement congestion pricing next year. Still, there are majny details to be worked out, and as Nicole Gelinas points out, the devil is very much in these policy details. Still to be decided are how to deal with a raft of requests for exemptions from pricing. According to the MTA, there have been requests for 122 categories of exemptions. As Gelinas points out, the easiest way to deal with this is to give no exemptions, especially for privately owned vehicles.

The most straightforward way to keep the base price low is for the MTA to approve zero exemptions for anyone driving private automobiles, which constitute 35 percent of core Manhattan traffic.

Gelinas argues that buses ought to be exempt (after all, they are getting cars off the city streets and providing a low cost alternative to car travel). The problem with exemptions is likely to be a persistent and gnarly one: The de facto exemption that police and many public employees have wrung from parking regulations doesn’t spawn a lot of hope in this regard.

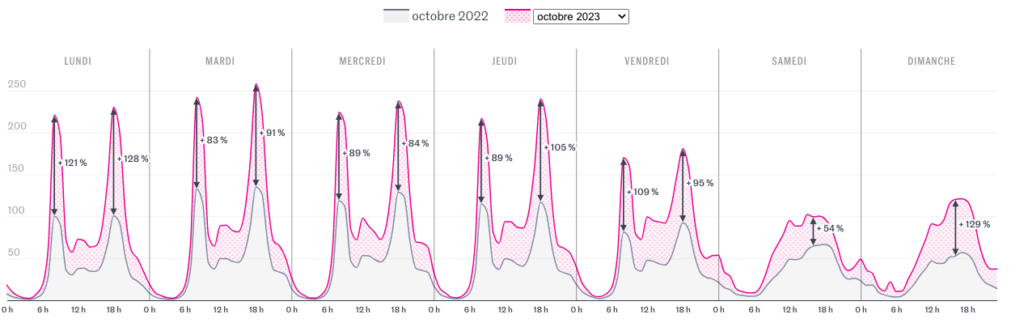

Cycling in Paris is up 50 percent in the past year. There’s a biking revolution happening in the City of Light. Mayor Ann Hidalgo has led an aggressive campaign to add bike lanes to the city’s streets, and Parisians are responding in dramatic fashion. It’s now the case the on many major arterials, the volume of traffic carried in bike lanes exceeds that carried in lanes open to car traffic. The following chart shows the change in bike traffic in Paris over the past 12 months (October 2022 to October 2023). There are notable increases, especially on weekdays and during peak hours: clearly cycling is carrying a significant and growing part of the urban transport load, especially at peak hours.

Call it a virtuous example of induced demand: if we build capacity for bike travel, people will bike. The fact that cycling continues to grow at this prodigious rate is a signal that a large scale commitment to redesigning urban transportation systems can quickly produce big changes in travel behavior.

The Rhode Island Attorney General challenges highway spending on climate grounds. Like many state highway departments, the Rhode Island DOT sees the latest round of federal largesse in the Bipartisan Infrastructure Law as a way to further pad its budget for widening highways. But wider roads simply trigger more car traffic, and increased pollution and recurring congestion. Rhode Island Attorney General Peter Neronha has formally challenged the state DOT’s plan to spend funds earmarked for fighting climate change on widening freeways. Like several state’s Rhode Island has a legal commitment to reduce greenhouse gases, and federal law requires agencies like RIDOT to show how they’ll make such reductions, but according to xxxx the RIDOT plan is wildly inadequate:

. . . a majority of the funding is earmarked for congestion management projects which, in RIDOT’s own words, “will not substantially ‘move the needle’ when it comes to carbon reduction.”4 That is, the Carbon Reduction Strategy identifies its carbonreducing expenditures as efforts mainly to make it easier for cars to travel—not the transformative changes necessary to remake a carbon-heavy sector to achieve Rhode Island’s reduction mandates. With just six years left before the first interim Act on Climate mandate, the State cannot afford to keep up the status quo and fail to identify needed actions to address the largest sector of emissions.

Would that other state Attorneys General would take up this cause.

Freeway fighter conclave gets national attention. Last month, Cincinnati hosted the first national convening of grass-roots freeway fighters from around the nation. Megan Kimble has profile of the conference and some of its attendees at Bloomberg. Kimble featured a number of local activists from around the country, including Portland’s Adah Crandall, leader of a group called “Youth vs. ODOT”

. . . there was a strong sense of solidarity among the attendees, who shared both their frustrations and hopes during a two-minute rant session at the end of the first day. Several younger organizers, such as Crandall, spoke about the intense urgency they feel to act in the face of the climate crisis. “Let’s cause some chaos and make state DOTs really afraid,” Crandall said.

New Knowledge

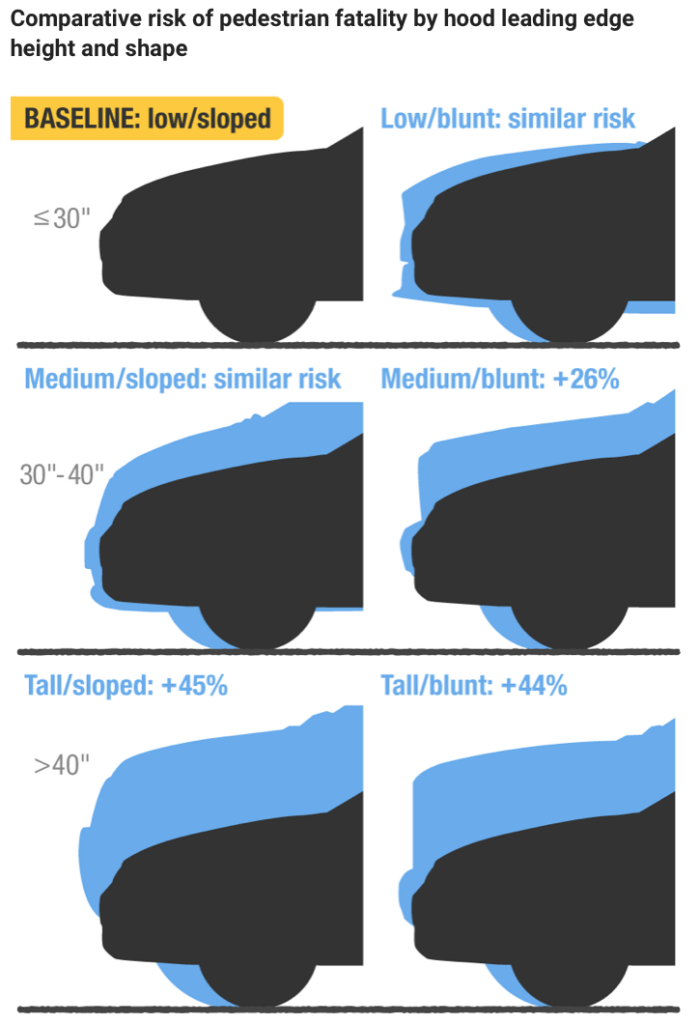

It’s official: taller, blunter vehicles are more deadly. For a long time, traffic safety advocates have pointed to the increasingly aggressive profile of the nation’s pick-up trucks. Grills and vehicle front-ends are taller and more massive, and as a result, more likely to deliver a deadly blow to the head, neck and torso of people walking or biking, and push them under a vehicles wheels, rather than striking someone’s legs and pushing them over the hood of a vehicle.

A new study from the Insurance Information Institute provides a grim confirmation of these fears. The IIHS study finds that towering newer pickup trucks and SUVs are 45 percent more likely to cause death or serious injury than today’s passenger vehicles. Here is the study’s key finding:

In general, vehicles taller than 35 inches were more dangerous to pedestrians than the shorter ones, mainly because they tended to cause more severe head injuries. Among vehicles taller than 35 inches, those with vertical front ends were more dangerous than those with sloped front ends. Torso and hip injuries from these vehicles were more frequent and severe.

There’s little question that the growth of monster trucks is correlated with the increase in pedestrian fatalities in the past decade or so. Hopefully the IIHS study will provide additional impetus for the National Highway Transportation Safety Agency (NHTSA) which regulates vehicles safety, to acknowledge this crisis, and take action. They can start, of course, by expanding vehicle safety ratings to include the safety of non-occupants; but that’s just a start. It’s long past time to regulate these deadly vehicles to protect people outside the monster truck

Hu, Wen, Monfort, Samuel S.,Cicchino, Jessica B., The association between passenger-vehicle front-end profiles and pedestrian injury severity in motor vehicle crashes,Insurance Institute for Highway Safety

November 2023, https://www.iihs.org/topics/bibliography/ref/2294