What City Observatory did this week

Pricing is a better, cheaper fix for congestion at the I-5 Rose Quarter. The Oregon Department of Transportation is proposing to squander $1.45 billion to widen about a mile and a half of I-5 in Portland—that’s right about $1 billion per mile. But a new analysis prepared by ODOT shows that pricing I-5 would do a better job of reducing congestion and improving traffic flow than widening the freeway—and would save more than a billion dollars.

ODOT has steadfastly (and falsely) maintained that pricing is “unforeseeable” and has excluded any analysis of the impact of pricing from the project’s Environmental Assessment (EA). But an ODOT technical memorandum shows that pricing I-5 would significantly reduce traffic congestion and speed traffic flow, without widening the I-5 roadway. The analysis also flatly contradicts EA claims that widening the highway won’t induce more traffic and also disproves claims made that the project will improve safety.

Must Read

Time for New York to stop giving away valuable street space for free. Don Shoup, described as the O.G. of parking policy, has pointed advice for the City of New York. The problem, Shoup notes, is that the city is awash in cars because it literally gives parking away for free. Most cars sit parked most of the day, or for days on end, and much of the traffic on city streets is cars searching for the elusive open parking space. All that could end if the city simply charged those who park on city streets for the privilege. Shoup has worked out that a fee that would keep about 15 percent of parking spaces open at any time would work wonders for the city’s transportation mess: less traffic, easier parking for those who pay, and plenty of revenue to improve local streets and subsidize mass transit. He writes:

Demand-based prices for curb parking resemble urban acupuncture: a simple touch at a critical point — in this case, the curb lane — can benefit the whole city. In another medical metaphor, streets resemble a city’s blood vessels, and overcrowded free curb parking resembles plaque on the vessel walls, leading to a stroke. Market prices for curb parking prevent urban plaque.

In New York, a minority of residents own cars, and they tend to have higher incomes than those who don’t own vehicles. Giving away parking hurts a majority of NYC residents, especially those of limited means. As Shoup says, it’s time to turn parked cars from freeloaders into paying guests.

False Equivalence: Bike- and bus-lanes are not the neighborhood destroyers that freeways were. Los Angeles Metro’s Chief Innovation Officer Selena Reynolds maintained in a recent interview that failing to get enough local assent for bike lanes or bus priority on urban streets was functionally a repetition of the arrogant destruction of neighborhoods by highway builders in the 1950s and 1960s (and in many places to this very day). Aaron Gordon of Vice strong disagrees.

While Reynolds frets that we are repeating the arrogant, top down approach of the past; Gordon points out that the public involvement process has been subverted, and really represents the interests of older, wealthier car-owning households, creating obstacles to more just forms of transportation.

While humility is a fine trait for a public official to have, it too often crosses over into policy nihilism, which is precisely the wrong lesson to take from the mistakes from the past. The result of this is well-intentioned, dedicated public officials comparing building bike lanes to urban highways. Not all bike or bus lane projects are perfect at their initial conception, but it is, in fact, possible to know if something is good or bad without hearing everyone’s opinion on it.

As Gordon points out, more than a million people were displaced by urban highway construction; there’s no evidence that anyone was displaced by a bike lane or bus lane. It wasn’t simply the process that was flawed, it was that highway were infinitely more destructive of the urban fabric. It’s useful to get public input to improve projects, but that shouldn’t dissuade public officials from acknowledging some modes are inherently more just and accessible than others.

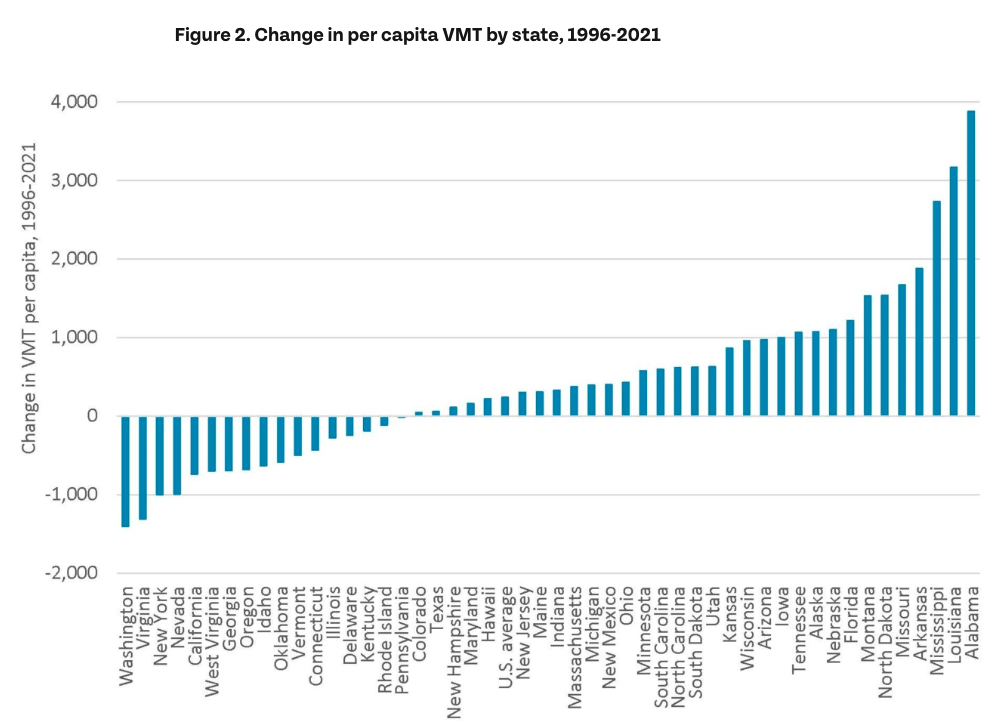

Driving less is possible. The Frontier Group’s Elizabeth Ridlington has a great data analysis looking at state-level trends in vehicle miles traveled per person. Transportation models (and much public discourse) seems to assume that daily travel is a fixed, irreducible quantity, but in reality, how far we travel (and by what means) can and does change over time. Critically, it reflects the way we build our communities and how much we subsidize car travel.

The policy takeaway here is that trends in vehicle miles traveled are not unchanging forces of nature. They are in fact, amenable to policy changes. Places that encourage more urbanization, and provide more options, tend to have much lower growth in VMT than sprawling, auto-dependent states.

New Knowledge

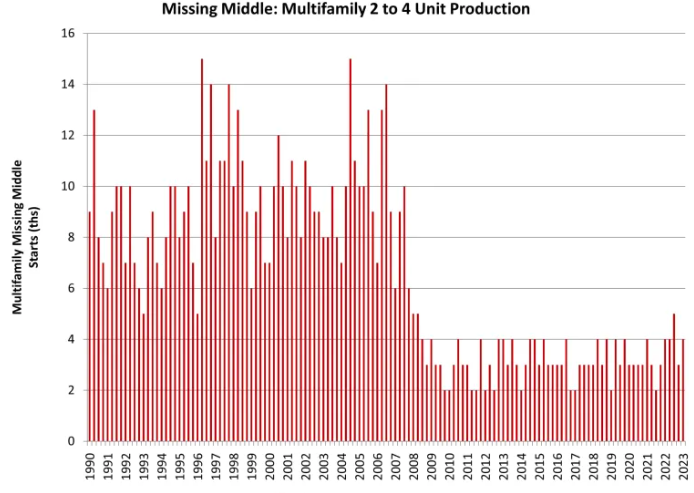

Missing Middle: Still MIA. One of the heartening developments in the housing debate has been increasing support for local and state policies that encourage so-called “Missing Middle” housing: duplexes, triplexes, four-plexes and other small scale, multi-family housing that fall between the traditional singe-family home and larger apartment buildings.

While there is definite progress on the policy front (Minneapolis, Oregon, Washington, and now California—have greatly liberalized the kinds of housing that can be built in many urban single family zones—the needle doesn’t appear to be moving much in terms of national housing supply.

Nationally, builders have been producing starting between about 2,00 and 4,000 new two- to four-unit structures each quarter since 2010. These levels of production are well below the average for the previous two decades.

Missing middle housing policies are a promising, and positive step in the right direction, but ultimately, the problem of housing production is one of scale, and so far, the missing middle policies have been too small to have much impact.

Robert Dietz, “Multifamily Missing Middle Flat at Start of 2023,” National Association of Home Builders: Eye on Housing, May 24, 2023.

H/t to: Luca Gattoni-Celli (@TheGattoniCelli)

In the News

Joe Cortright’s analysis of the ODOT was cited in by the Sisters Nugget: Issuing debt for major highway expansions could jeopardize re-opening Cascade pass highways each Spring.