What City Observatory did this week

There’s plenty of time to fix the Interstate Bridge Project. Contrary to claims made by OregonDOT and WSDOT officials, the federal government allows considerable flexibility in funding and re-designing, especially shrinking costly and damaging highway widening projects

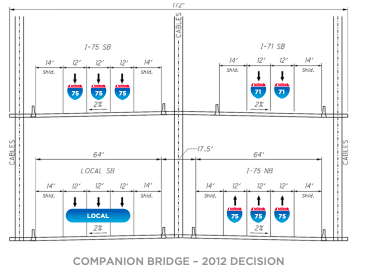

In Cincinnati, the $3.6 billion Brent Spence Bridge Project

- Was downsized 40 percent without causing delays due to environmental reviews

- Got $1.6 billion in Federal grants, without only about $250 in state funding plus vague promises to pay more

- Is still actively looking to re-design ramps and approaches to free up 30 acres of downtown land

Within the past year, the Ohio and Kentucky transportation departments pared the size of the bridge by almost half, without prolonging the environmental review process or sacrificing federal funds.

For years, the managers of the Interstate Bridge Project have been telling local officials that if they so much as changed a single bit of the proposed IBR project, that it would jeopardize funding and produce impossible delays. Asked whether it’s possible to change the design, and they frown, and gravely intone that “our federal partners” would be displeased, and would not allow even the most minor change. It’s a calculated conversation stopper—and it’s just not true.

Must Read

The Playground City? The persistence of work-at-home and the surge in office vacancies in downtowns has people worried about the future of cities. One of the nation’s leading urban economists, Ed Glaeser, penned an op ed in the New York Times with his MIT colleague Carlo Ratti, foreseeing a predicting the emergence of the “playground city.” They argue that New York’s economy is shifting from office work to entertainment:

New York is undergoing a metamorphosis from a city dedicated to productivity to one built around pleasure. . . The economic future of the city that never sleeps depends on embracing this shift from vocation to recreation and ensuring that New Yorkers with a wide range of talents want to spend their nights downtown, even if they are spending their days on Zoom. We are witnessing the dawn of a new kind of urban area: the Playground City.

Glaeser makes the point that, throughout history, cities like New York have successively re-invented themselves in the face of economic and technological changes. New York’s economy was once fueled by trade and manufacturing, but in recent decades has been propelled by financial and professional services. They suggest that the city can, and will, reinvent itself again.

Oddly, the column makes no reference to Glaeser’s own seminal article “The consumer city” published two decades ago. And the term “playground city” is an echo of Terry Nichols Clark’s 2003 book “The City as an Entertainment Machine.” These works—and our own City Advantage (2007)— make the case that people don’t live in cities simply to be close to jobs, but that cities offer compelling advantages as places to live, interact with others, and access a diverse array of goods, services and experiences. In cities, more different and varied goods, services and people are close at hand, and it’s easier to discover and explore new things.

Cities aren’t merely playgrounds: they’re places we can grow and lead richer and fuller lives. That’s why urban centers will persist and flourish, even if office employment never returns to its pre-pandemic peak.

Want better transit? Stop squandering money widening freeways. Too often, transportation policy is co-opted by “all of the above” multi-modalism: we can only improve transit if we have a “balanced” program that includes more money to move cars faster. The Transit Center pushes back against this bankrupt thinking, calling New York State leaders to cancel two big (and counterproductive) freeway widening projects, and instead spending the money on improving transit. Under the new federal infrastructure law, states and localities have a choice, and there is a trade-off: most federal formula funds can be “flexed” from highways to transit, if state and local leaders agree.

These phony “balanced” investments inevitably encourage more car traffic, more sprawling development, and undercut the effectiveness and raise the cost of operating transit. In the face of a climate and road safety crisis, we have to set priorities.

Must Listen. San Diego Public Radio (KPBS) has a new program: “Freeway Exit,’ exploring the intimate connection between freeways and the nation’s cities. The program is hosted by KPBS metro reporter Andrew Bowen, “Freeway Exit” relates the forgotten history of San Diego’s urban freeway network, and how freeways divided communities and created inequities that still exist today. The series also shows how freeway culture has contributed to the climate catastrophe we’re now facing, and how reimagining our freeways could be a key part of the solution. Episode two features some vintage audio from the 1950s that captures the sense of unquestioned progress that enveloped cars and freeway building–before the social and environmental costs of car dominance became evident.

In the News

The Portland Mercury quotes City Observatory’s Joe Cortright, in an article entitled: “Build It and They Will Pay: ODOT’s Plans for Tolling Generate Broad Backlash.”