What City Observatory did this week

More induced travel denial. Highway advocates deny or minimize the science of induced travel. We offer our rebuttal to a reason column posted at Planetizen, attempting to minimize the importance of induced demand for highways.

Induced travel is a well established scientific fact: any increase in roadway capacity in a metropolitan area is likely to produce a proportional increase in vehicle miles traveled. Highway advocates like to pretend that more capacity improves mobility, but at best this is a short lived illusion. More mobility generates more travel, sprawl and costs. In theory, highway planners could accurately model induced travel; but the fact is they ignore, deny or systematically under-estimate induced travel effects. Models are wielded as proprietary and technocratic weapons to sell highway expansions.

Must Read

Consultants gone wild. There’s little dispute that the US has some of the highest urban rail construction costs on the planet. The big question surrounding this unfortunate American exceptionalism is, “Why?” Writing at Slate, Henry Grabar summarizes a recent study that poses a provocative answer: It’s our excessive reliance on consultants. The study comes from Eric Goldwyn, Alon Levy, Elif Ensari, and Marco Chitti of New York University’s Transit Costs Project, who’ve taken a close look at construction projects in the US and around the world.

Not only are the consultants themselves more expensive than permanent staff, there are two related problems: incentives and capacity. Consultants don’t get paid for building subways–they get paid for studying things and offering advice. That gives them strong financial incentives to prescribe further study and more advice. The related problem is capacity: the agencies commissioning all this consultant work have to have the capacity to read, digest and act on the expertise, and the reductions in staff, and the diminished expertise in the public sector mean that they may not have the ability to do so–or critically, to ask hard questions. And for the record, the problem of excessive consultant costs isn’t limited to transit projects: The Oregon and Washington highway departments spent nearly $200 million on planning and engineering for the never-built Columbia River Crossing a decade ago, and are on track to spend more than $200 million for planning and engineering of its star-crossed successor, the Interstate Bridge Replacement–with most of this money going to years upon years of consulting contracts.

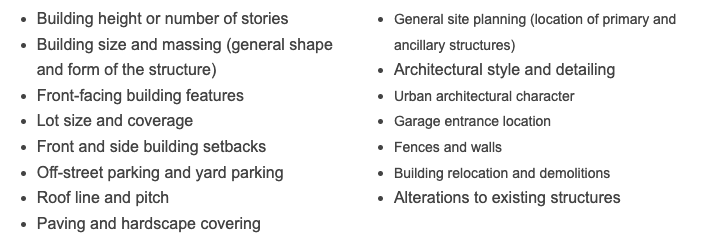

They dare not call it zoning. Houston’s au courant NIMBYs want to authorize conservation districts. It sounds innocent enough, the City of Houston wants to authorize neighborhoods to form “conservation districts” to allow a majority of existing landowners in a particular area to impose restrictions on new development, including minimum lot sizes, building setbacks, roof pitches and the like. A conservation district could limit any of these features:

Ostensibly, the purpose of the conservation districts is to protect neighborhoods from untoward change. Advocates point to the city’s famous Fourth Ward, which lost most of its historic housing, and has seen a recent wave of redevelopment, which many residents consider “out-of-character” with its history. If this all sounds familiar, it’s because it’s awfully similar to traditional exclusionary zoning measures. Recall that zoning was originally designed to protect established neighborhoods from scourges like slaughterhouses, tanneries, and, of course, apartments. In some cities, historic designations have become the more fashionable way to cloak exclusion with the color of law. And Houston, which purportedly has no zoning–at least not by that name–would never implement it, except that these conservation districts could easily be applied almost anywhere. It’s an open invitation for NIMBY’s to craft their own bespoke zoning. There’s apparently no limit to the number of such districts that can be created, or their size; so long as 51 percent of property owners agree, and the City Council approves, you can have your very own district. Because wealthier neighborhoods likely have the political capital and wherewithal to navigate the process, its probable that, just like single family zoning, this will become a tool of exclusion.

Downtown Chicago gains population, despite the pandemic. The received wisdom about the pandemic is how bad it was for city centers, especially due to a decline in office occupancy because of increasing work at home. But a new survey from downtown Chicago underscores the changing economic role of city centers as prime residential locations, especially for well-educated young adults. As reported in Bloomberg CityLab, downtown Chicago’s population grew by xx,xxx since before the pandemic. The study looked at population in Chicago’s Loop (the area bordered by the elevated train that circulates around down town.

Most of the Loop’s population is 25 to 34 years old, with more than 80% living alone or with one person. Almost half don’t own a car and the majority cite the ability to walk to places, the central location and proximity to work as top reasons for living downtown. The future of the Loop will also be more residential. Another 5,000 housing units are expected to be added by 2028, bringing the district’s total population to 54,000, according to the report

New Knowledge

A hidden climate time bomb in US home values. A new study published in Nature estimates that home values in flood prone areas across the US are significantly over-priced because markets are ignoring likely damage from climate change.

When buyers pay for homes, they may not be aware of the likely damage from climate change, especially due to the increased risk of flooding. To some extent, buyers already recognize that homes located in flood prone areas may be less valuable than otherwise similar homes in drier places. Overall, homes in the 100-year flood plane sell at about a 3 percent discount to otherwise similar homes elsewhere. But there are systematic patterns in how well markets accurately reflect flood risk. The author’s conclude:

. . . residential properties exposed to flood risk are overvalued by US$121–US$237 billion, depending on the discount rate. In general, highly overvalued properties are concentrated in counties along the coast with no flood risk disclosure laws and where there is less concern about climate change.

This study uses home value data and new data on increasing flood risks to identify the discrepancy between current market values, and values that would reflect a more realistic appraisal of likely climate risk.

There are distinctly regional patterns to climate risk. The greatest concentration of losses (relative to the total fair market value of properties) is along the Gulf Coast, and in Appalachia and in the Pacific Northwest.

Property overvaluation as a proportion of the total fair market value of all properties.

Property overvaluation as a proportion of the total fair market value of all properties.

A big policy question going forward is how we incentivize people to avoid building in high-risk areas and allocate the costs of climate related damages. Historically, the National Flood Insurance Program has paid out much more in benefits than it has collected in premiums, and still fails to fully account for growing climate risk. Over time, higher premiums will shift some of these climate costs to property owners in risky areas, but Congress has capped premium increases, which slows the adjustment. In theory, mortgage lenders should be less willing to lend for housing in risky areas, but as the authors point out, many use federal loan securitization to disproportionately shift the riskiest properties into the portfolios of federally guaranteed home lending programs.

Jesse D. Gourevitch, Carolyn Kousky, Yanjun (Penny) Liao, Christoph Nolte, Adam B. Pollack, Jeremy R. Porter & Joakim A. Weill

Unpriced climate risk and the potential consequences of overvaluation in US housing markets,” Nature Climate Change (2023).

https://www.nature.com/articles/s41558-023-01594-8

In the News

The Urbanist and Investor Minute republished our commentary on the Oregon Department of Transportation’s plans for tolls of as much as $15 to travel between Wilsonville and Vancouver under the title “How to finance a highway spending spree”

Thanks to Streetsblog for their shout out on our commentary about induced demand; as they put it: “How is it that, despite all evidence to the contrary, anyone still believes widening roads will reduce congestion?”