What City Observatory did this week

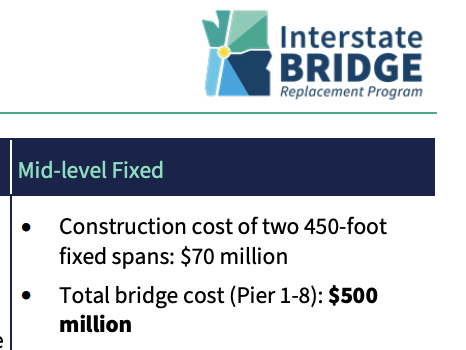

Why does a $500 million bridge cost $7.5 billion? For almost two decades the Oregon and Washington highway departments have been saying they want to replace the I-5 bridges over the Columbia River connecting Portland and Vancouver. Late last year, they announced that the total cost of the project could run as high as $7.5 billion. But the project’s detailed comparison of different bridge types shows that the actual structure crossing the river will cost only about $500 million. Here’s the detail from the project’s “river crossing” report:

The reason the project is so expensive is not because of the bridge, but because the two agencies plan to rebuild seven interchanges on either side of the river, widen the freeway to a dozen lanes, and build almost a mile of elevated viaducts to connect their high river crossing to the existing highway. As then Congressman Peter DeFazio observed a decade ago, the “problem was thrown out to engineers, it wasn’t overseen: they said solve all the problems in this twelve-mile corridor and they did it in a big engineering way, and not in an appropriate way.” If this project were simply about replacing the actual bridge, rather than widening the freeway, and rebuilding interchanges, it would be vastly cheaper.

Civil rights or repeated wrongs: Houston moves ahead with a $10 billion I-45 Freeway. We publish as a guest commentary an analysis prepared by the Center for American Progress infrastructure expert Kevin DeGood, who looks at the aftermath of a negotiated settlement between FHWA and TxDOT to a civil rights complaint against the giant freeway widening project.

As DeGood points out, the settlement offers mere procedural window dressing, largely just masking past damage, and setting the stage for another round of neighborhood destruction by freeway construction.

Must Read

More flat earth thinking from highway engineers. Who knew that building more roads was the key to reducing greenhouse gas emissions? IN a guest opinion for Greater Greater Washington, Bill Pugh takes a close look at the Washington DC region’s bold climate goals, contrasting them with its stated “build more highways” transportation strategy. Throughout the region, highways agencies routinely repeat the discredited claim that they’ll reduce greenhouse gas emissions by reducing the amount of time cars spending idling in traffic. As Pugh points out, the thousand miles or so of additional lane-miles of roadway the region’s jurisdiction’s plan to build will generate as many as 3 to 4 billion additional miles of auto travel every year–more that wiping out any gains from “less idling.”

Scapegoating (the wrong) greedy investors for housing unaffordability. The indispensable Jersusalem Demsas once again takes out the trash on a pet housing market theory: blaming hedge funds and investment bankers for housing unaffordability. Demsas digs deep into the statistics that people use to blame big finance for invading housing. Numbers focus on recent sales, rather than the entire housing stock, and more importantly, conflate “institutional investors” with all investors–which includes a lot of mom-and-pop homeowners who rent out a house or two. Institutional finance represents only a small share of new purchases, and has even peaked in some markets. Overall, Demsas concludes that the flow of institutional capital into single family home purchases is an effect, rather than a cause of unaffordability:

“Institutional Investors” are not why rents are so high or why homeownership is out of reach for so many. Investors are not driving the unaffordability; they are responding to it. Many different investors are all flocking into the housing market; what is most relevant is the fundamental reason they are all being drawn there. Housing is primarily unaffordable in this country because of persistent undersupply. In fact, institutional investors are entering the single-family-home market precisely because supply constraints have led to skyrocketing prices.

The imbalance of demand and supply is really what’s behind the unaffordability, and scapegoating institutional investment maybe politically popular, but misses the mark. And, as we’ve pointed out at City Observatory, institutitonal investors are pikers in the housing market: it is incumbent owners that racked up literally trillions of dollars in capital gains in the last few years due to growing housing unaffordability.

New Knowledge

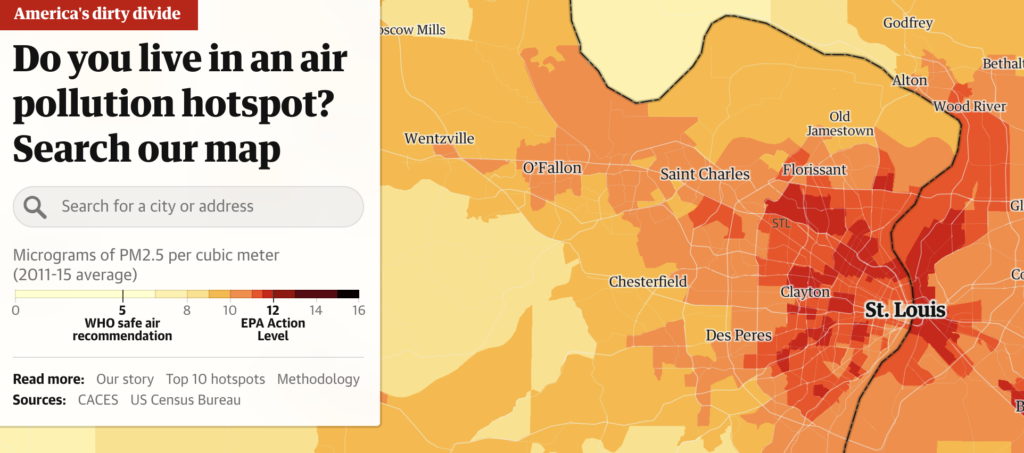

PM 2.5 pollution across the United States. There’s a growing awareness that fine particulates (pollution smaller than 2.5 microns) cause significant health effects. These tiny particles can be inhaled deeply into the respiratory system, and prolonger exposure leads to higher rates of asthma and other respiratory diseases.

A new mapping project published by The Guardian looks at the geographic variation in PM 2.5 (particulate matter smaller than 2.5 microns) across the US.

Maps are available for the entire nation and show the hot spots for the concentration of these dangerous small particles. Here, for example, is the map of the St. Louis region.

The Guardian has looked at the pattern of hot spots compared to the demographics of local neighborhoods, and–unsurprisingly–finds that there’s a strong correlation between race, ethnicity and exposure to fine particle pollution. People living in predominantly Black and brown neighborhoods tend to be exposed to much higher levels of PM 2.5.

. . . across the contiguous US, the neighborhoods burdened by the worst pollution are overwhelmingly the same places where Black and Hispanic populations live. Race is more of a predictor of air pollution exposure than income level, researchers have found.

The Guardian’s maps and findings are based on research from scientists at the University of Washington and other institutions that have developed a sophisticated model of the generation and transmission of these particles. Data are from the years 2011 to 2015.

Erin McCormick and Andrew Witherspoon, “America’s dirty divide:

US neighborhoods with more people of color suffer worse air pollution,” The Guardian, March 8, 2023

In the News

Todd Litman of the Victoria Transportation Policy Institute, cited our parable of how Louisville showed how to solve traffic congestion at Planetizen.