What City Observatory did this week

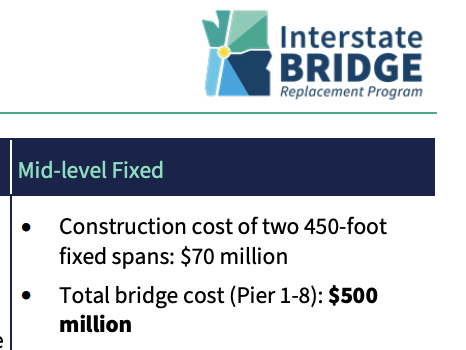

Why does a $500 million bridge replacement cost $7.5 billion? For the past several years, the Oregon and Washington highway departments have been pushing for construction of something they call the “Interstate Bridge Replacement” project, which is a warmed-over version of the failed Columbia River Crossing. The project’s budget has ballooned to as much as $7.5 billion. New documents have come to light that show that the “bridge replacement” part of the Interstate Bridge Replacement only costs $500 million, according to new project documents. So why is the overall project budget $7.5 billion?

We dig into the limited information provided by the state DOTs. There are two big answers to the question as to why a $500 million bridge ends up costing $7.5 billion. The shortest and simplest answer is that it is really a massive freeway-widening project, spanning five miles and seven intersections, not a “bridge replacement.” A longer (and taller) answer is that the cost of the river crossing is inflated because of the need to raise the roadway to clear a 116-foot navigation channel. This fixed span requires half-mile long elevated viaducts on both sides of the river, and the need to have interchanges raised high into the air make the project vastly more complex and expensive. As then-Congressman Peter DeFazio observed of the project some years ago, ““I kept on telling the project to keep the costs down, don’t build a gold-plated project . . . They let the engineers loose, . . . it wasn’t overseen: they said solve all the problems in this twelve-mile corridor and they did it in a big engineering way, and not in an appropriate way.”

Must Read

USDOT and TXDOT “settle” Houston I-45 civil rights complaint. It’s well established that freeway construction has been an engine of segregation in US cities. Belatedly, the US Department of Transportation is acknowledging this fact, and has spent the last two years investigating the whether the Texas Department of Transportation’s plan to widen I-45 through Houston complies with civil rights laws. USDOT has entered into an agreement with TXDOT, which includes allocating $30 million to building affordable housing, building trails and greenspaces, monitoring pollution and (surprise!) holding more meetings. The housing money and amenities are no doubt welcome, but that hardly undoes the damage done by this freeway and its pending expansion. Houston Public Media quoted Tiffany Valle, an organizer with Stop TxDOT I-45:

“The agreement that TxDOT and the FHWA have voluntarily agreed upon, it’s really just more of the same,” Valle said. “They are continuing to allow the destruction of Black and brown communities, something that has been done for decades.”

Opponents of the project won’t be mollified by these superficial steps. They will fight on, as they should.

America Walks grades the USDOT’s “Reconnecting Communities” Grants. https://americawalks.org/reconnecting-communities-grant-awardees/. America Walks calls out some of the positive steps–like grants to advance freeway removal efforts in Buffalo, Long Beach and Kalamazoo. But at the same time, USDOT failed to provide funds to some other efforts that could clearly benefit from these resources, like the Claiborne Avenue Alliance in New Orleans. And some of the project are simply providing state highway departments with a generous dose of greenwash for clearly egregious highway widening projects, as in Austin. Too much of the money, in fact, simply went to state highway agencies, who historically caused most of the problems this program aims to solve, and who in many cases are half-hearted or duplicitous in their support for really rethinking the effects of urban highways. Too seldom has USDOT taken the opportunity to empower local groups to fundamentally challenge the highway orthodoxy. They write:

Only three of the 39 winning planning grant applications have a community-based organization as their lead applicant. If USDOT is serious about developing reconnecting communities solutions tailored to local needs, it should aim to fund more community-based organizations so they can bring information and professional expertise from outside the normal channels of infrastructure development that in the past haven’t served residents.

Pity the poor airports–victims of climate change. Our friends at the Brookings Institution have a new report detailing the costs airports will have to bear to cope with the effects of climate change. Many airports are built on or near floodplains, and are vulnerable to severe weather and flooding, which are likely to become more common with climate change. It’s likely that they’re under-prepared, and more spending is needed to harden airports against these effects. The Brookings Report makes a good case, but largely ignores one salient detail: Airports themselves are some of the most carbon-intensive activities in any metropolitan area.

The business model of every airport hinges primarily on sources of revenue tied directly to greenhouse gas emissions: jet aircraft and parking garages. We ought to have a national program that reflects the costs of climate adaptation back on big greenhouse gas emitters. Air travel fees should not only pay for hardening airport infrastructure, but offsetting the damage from air travel related emissions on the rest of the economy as well. Maybe if air travel paid these costs, other alternatives, like rail, would look more economically feasible.

New Knowledge

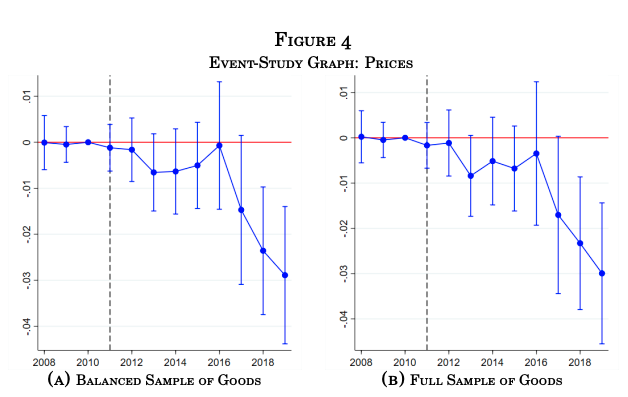

New housing helps drive down local food prices and improve product variety. Over the past few years there’s been of spate of research confirming what economists have long held: building new housing in urban areas tends to hold down rents. A new study from Montevideo looks at a related issue: the effect of new housing on prices of goods in local stores.

Its long been a trope of the gentrification debate that new development leads to the demise of long-established and perhaps prosaic local stores and their displacement by twee boutiques and overpriced shops. But focusing on prices actually charged in local markets, and counting the variety of goods available to local shoppers, this study from Fernando Borraz and his colleagues shows just the opposite: the construction of new housing tends to lower the price and increase the variety of products on offer in local stores.

The Borraz, et al, paper is an extension of a line of research from Jesse Handbury, who observed that residents of larger cities actually face lower prices for a market basket of goods and services, because cities provide a better fit between what consumers want and what’s actually available. It’s also more proof for Ed Glaeser’s thesis about the “consumer city—that the competitive advantage of cities stems not simply from greater productive efficiency, but because they offer residents a more diverse (and less expensive) array of goods, services and experiences.

What this paper means in practice is that the new neighbors who live in the apartments that get built in your neighborhood provide the customer base to attract more merchants, and increased numbers lead stores to compete harder for their trade.

Fernando Borraz, Felipe Carozzi, Nicolás González-Pampillón and Leandro Zipitría, Local retail prices, product varieties and neighborhood change, Centre for Economic Performance, Discussion Paper No.1822 January 2022 ISSN 2042-2695