What City Observatory did this week

What computer renderings really show about the Interstate Bridge Replacement Project: It’s in trouble. The Interstate Bridge Project has released—after years of delay—computer graphic renderings showing possible designs for a new I-5 bridge between Vancouver and Portland. But what they show is a project in real trouble. And they also conceal significant flaws, including a likely violation of the National Environmental Policy Act. Here’s what they really show:

- IBR is on the verge of junking the “double-decker” design it’s pursued for years.

- It is reviving a single decker design that will be 100 feet wider than the “locally preferred alternative” it got approved a year ago.

- The single deck design is an admission that critics were right about the IBR design having excessively steep grades.

- The single deck design has significant environmental impacts that haven’t been addressed in the current review process; The two states ruled out a single deck design 15 years ago because it had greater impacts on the river and adjacent property.

- IBR’s renderings are carefully edited to conceal the true scale of the bridge, and hide impacts on downtown Vancouver and Hayden Island.

- IBR has blocked public access to the 3D models used to produce these renderings, and refused to produce the “CEVP” document that addressed the problems with the excessive grades due to the double-deck design.

- The fact the IBR is totally changing the bridge design shows there’s no obstacle to making major changes to this project at this point.

Must Read

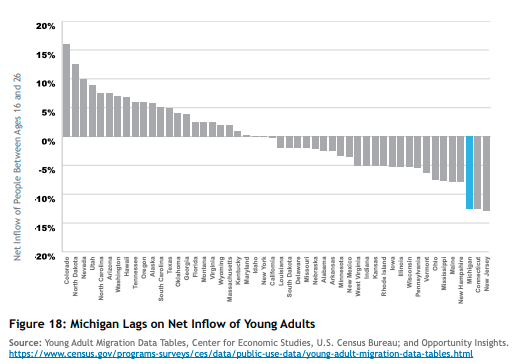

Economic development hinges on the ability to attract talent. Richard Florida and his colleagues have prepared a new economic analysis for the state of Michigan. It highlights many of the state’s strengths (it’s strong intellectual capacity and established manufacturing base in transportation), but importantly stresses the state’s long term economic success hinges on doing a better job of attracting talented workers. The report–Michigan’s Great Inflection–contains some insightful information of interest to all states.

In particular, the report highlights which states are–and aren’t–doing a good job of attracting talented young workers. And, although Michigan does a reasonably good job of hanging on to its own youth, it does very poorly in attracting young, well-educated workers from elsewhere.

The study acknowledges the importance of bolstering current industries and institutions, but emphasizes growing, retaining and attracting talent:

To ensure the long-run prosperity of its industries, communities, and people, Michigan must focus its economic development strategy on bolstering and aligning the capabilities of its leading corporations, universities, and startups in critical transformational technologies. As importantly, if not more so, the state must enhance its strategies for generating, retaining, and attracting the talent required to compete in this new economic environment.

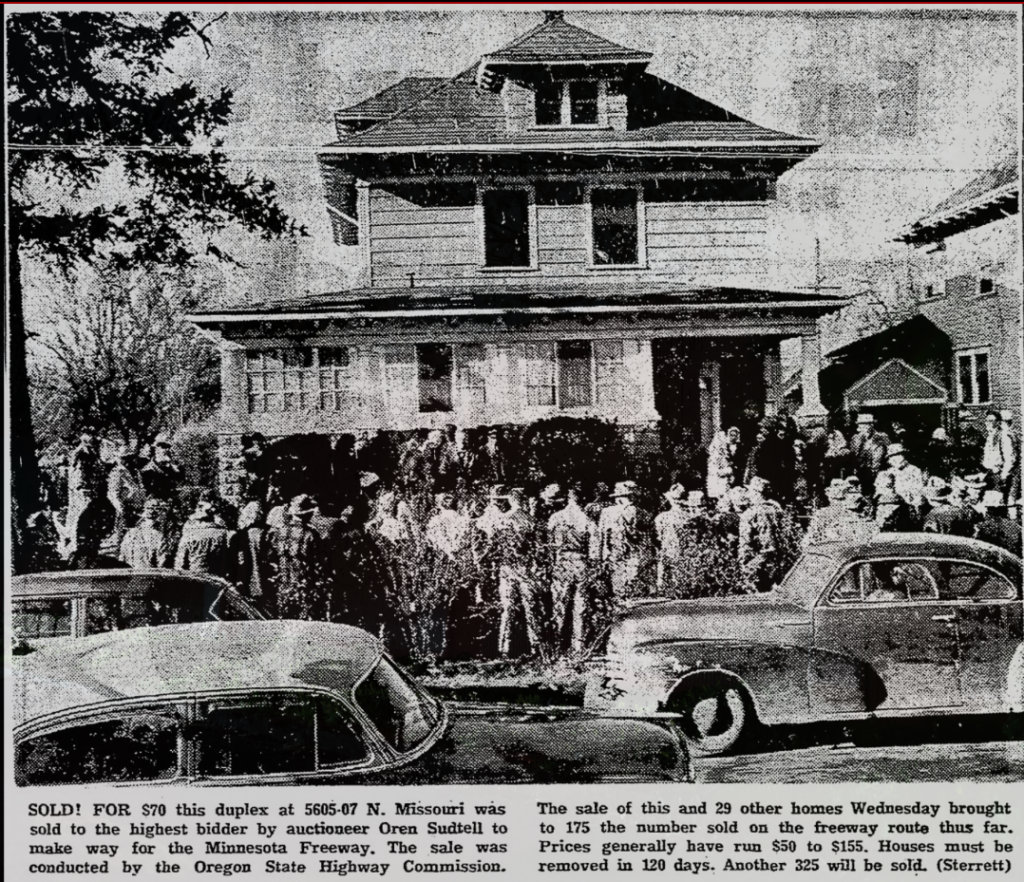

A newspaper’s mea culpa for supporting a racist freeway project. The Portland Oregonian has a fascinating and detailed retrospective on how its coverage of freeway construction and urban renewal in the 1950s and 1960s reinforced and amplified the destruction of the city’s segregated Black Albina neighborhood.

The narrative relates how the newspaper paid scant attention to the dislocation of families and businesses by the construction of Portland’s Memorial Coliseum, the expansion of Emmanuel Hospital, and three major state highway construction projects, which collectively led to the demolition of hundreds of homes, and prolonged population and economic decline in Albina.

The state highway department, now the Oregon Department of Transportation, purchased it and other homes along the route and then offered them at auction, allowing bidders to salvage sinks, furnaces and fixtures before tearing down the houses. The Oregonian covered one auction in 1961, noting that the state highway department sold 175 condemned homes for between $50 and $155 apiece. “Even the shrubbery is included,” The Oregonian wrote. Former residents’ identities were not.

Ironically, even as this coverage appears in the local newspaper, the Oregon Departmetn of Trnasportation is proposing to spend $1.45 billion to widen Interstate 5 through the Albina neighborhood, further increasing traffic and pollution. ODOT’s plan calls for widened overpasses it describes as freeway covers, but beyond building the overpasses, ODOT is proposing to spend nothing to restore the damage done to the neighborhood, much less replace the hundreds of houses it demolished.

New Knowledge

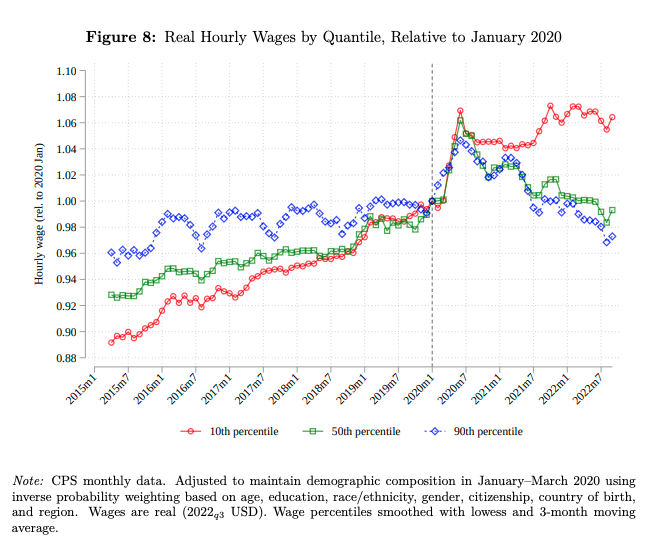

The big compression: Why a tight labor market is a powerful force for equity. The big economic lament for most of the past half century has been widening wage and income inequality. But a funny thing has happened in the past few years: The big gains in income have come at the low end of the labor market. Wage increases have been highest for those in the lowest wage jobs.

In a new paper fromDavid Autor, Arindrajit Dube and Annie McGrew, quantifies the sea change in labor markets.

Wages went up for all workers following the onset of the pandemic, but went up most, and stayed higher, for the lowest wage workers. Another key development in the market was increased job changing among lower wage workers. Low unemployment rates prompted firms to bid up wages and gave workers the opportunity to move to other better paying jobs. As the authors conclude:

Labor market tightness following the height of the Covid-19 pandemic led to an unexpected compression in the US wage distribution that reflects, in part, an increase in labor market competition. . . the pandemic increased the elasticity of labor supply to firms in the low-wage labor market, reducing employer market power and spurring rapid relative wage growth among young non-college workers who disproportionately moved from lower-paying to higher-paying and potentially more-productive jobs

The changes are large: what’s happened in the past few years has erased about a quarter of the increase in the college wage premium since 1980. Tight labor markets give employers strong incentives to hire and train workers, and improve their productivity. And they give workers the opportunity to go somewhere else if they’re not happy or feel they aren’t being adequately rewarded for their work. To be sure, we see lots of complaints from employers that they can’t find the worker’s they need, but this is actually an indication that the labor market is working better for workers, and that’s turned out to benefit low wage workers the most.

The Covid-19 pandemic was a tragedy, to be sure. But its economic aftermath: a very strong fiscal stimulus which produced tight labor markets, has generated substantial economic benefits for low wage workers, whose economic plight has been worsening for decades.

David Autor, Arindrajit Dube and Annie McGrew, The Unexpected Compression: Competition at work in the low wage labor market, Working Paper 31010, National Bureau of Economic Research, http://www.nber.org/papers/w31010