What City Observatory did this week

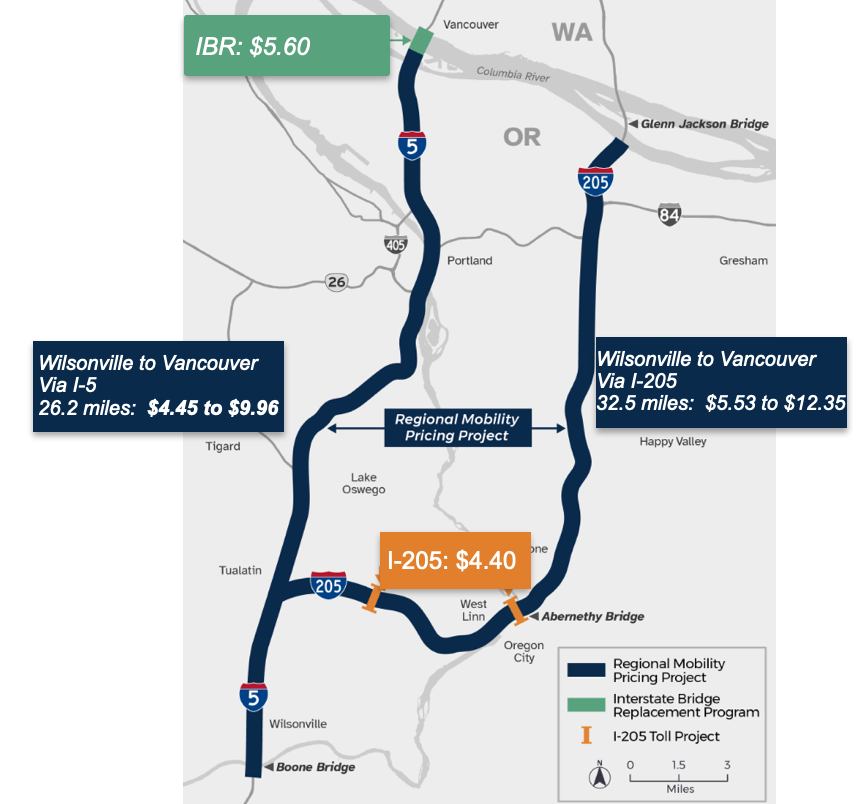

Driving between Vancouver and Wilsonville at 5PM? ODOT plans to charge you $15. Under ODOT’s toll plans, A driving from Wilsonville to Vancouver will cost you as much as $15, each-way, at the peak hour. Drive from Vancouver to a job in Wilsonville? Get ready to shell out as much as $30 per day.

Tolls don’t need to be nearly this high to better manage traffic flow and assure faster travel times. The higher tolls are necessitated by the need to finance ODOT’s multi-billion dollar highway spending spree. ODOT is telling everyone to get ready for tolls, but they’re being close-mouthed about how much tolls will be. Here’s what they’re planning, according to documents obtained by City Observatory.

- Tolls on the I-205 Abernethy and Tualatin River Bridges will be $2.20 each at the peak hour. (Orange)

- Tolls on the I-5 Interstate Bridge will be up to $5.69 (Green)

- In addition to these tolls, drivers on I-5 and I-205 will pay tolls of 17 cents to 38 cents per mile during peak hours. Twenty miles of driving on I-5 or I-205 will cost you between $3.40 and $7.60. (Blue)

Road pricing could be an effective means to reduce congestion. But the toll levels ODOT is proposing are really designed to maximize revenue, not to manage congestion. Tolls could be vastly lower if set just high enough to allow a free flow of traffic. And there’s no need to do congestion pricing during off-peak hours when there’s plenty of under-used roadway space. But ODOT isn’t interested in managing traffic, it just wants more money to build things.

Must Read

Time to sue the bleeping engineers for malpractice. Jeff Speck has had enough. The author of Walkable City, has (through years of work, public speaking and two editions of his book) exposed the profound biases in the dominant transportation planning paradigm. While there’s considerable blame for increasingly large and dangerous sport utility vehicles and our sprawling, auto-dependent development patterns, the way we design our roads is major contributor to America’s high (and rising) traffic fatality rate.

Put simply, the roadway design standards enshrined by our nation’s professional civil engineers are unnecessarily deadly to the point of criminal negligence. It’s time to place blame and demand change. . . . Engineers routinely design streets to support (and therefore invite) speeds well above the posted speed limit. Then, when speeding is observed on these streets, the manual published by the Federal Highway Administration requires that the speed limit be raised.

Highway design emphasizes speed and throughput over safety, particularly for those walking and biking. While there’s plenty of specific policies that can be changed, Speck argues its time to assign legal liability to highway engineers for their dangerous designs. Perversely, they’re now frequently fearful to make changes that might improve safety (like unique paint designs for crosswalks) because such innovations are approved in the auto-centric highway design manuals. It’s a deeply flawed system, desperately in need of radical change.

Right on cue, the Oregon Department of Transportation has decided the best way to improve pedestrian safety is to . . . close lots of crosswalks. Faced with a growing epidemic of traffic violence, OregonDOT has hit on a new strategy. As Bike Portland reports, it plans to close crosswalks on more than 180 Portland area roadways that it controls. Most egregious, the agency plans to close xx crosswalks on dangerous Powell Boulevard, a roadway the claimed the life of Portland chef Sarah Pilner just a few months ago.

Of course, closing the crosswalks doesn’t make the roadway any safer, it just effectively eliminates the criminal penalties (and bureaucratic responsibility) when motorists end up hitting pedestrians. And it’s a clever way for the agency to avoid making the crossing actually safer (or comply with the Americans with Disabilities Act). If it’s not a crosswalk, ODOT doesn’t have to fix it, or bring it up to ADA standards.

The ironic insult added to injury of this policy, of course, is that all of the crosswalk closures will substantially lengthen the distances that pedestrians have to walk to legally cross these roadways. Many closures will add several minutes to the amount of time needed to reach an otherwise nearby destination: and OregonDOT would never, ever tolerate a safety measure that forced a motorist to experience a similar level of delay. As Jeff Speck observed, these policies make it clear that highway departments value to motorists’ time above pedestrians lives and limbs.

In the News

The Oregonian quoted City Observatory’s analysis of planned tolls on Portland area roadways in its article: “Tolls are coming to Portland-area freeways, and even tolling fans worry they’ll stack up.”

Willamette Week quoted City Observatory’s Joe Cortright on the Interstate Bridge Project’s plans to dramatically redesign a proposed Columbia River Bridge, an implicit admission that critics have been right all along.