What City Observatory did this week

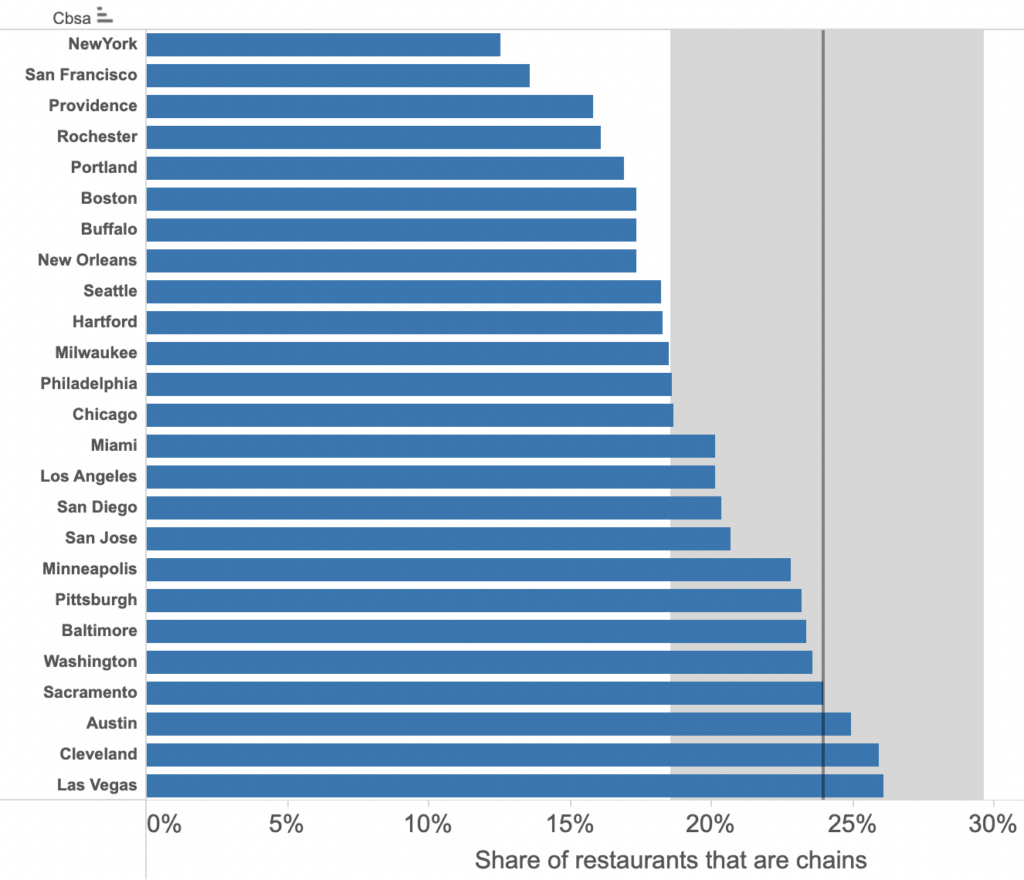

Eating local: Why independent, local restaurants are a key indicator of city vitality. Jane Jacobs noted decades ago that“The greatest asset a city can have is something that is different from every other place.” While much of our food scene is dominated by national chains, some cities have many, many more locally owned independent restaurants than the the norm. And independent restaurants get overwhelmingly higher ratings than chains. We’ve used Yelp data to estimate the share of independent, local restaurants in large US metro areas, and come up with this ranking.

Unsurprisingly, New York and San Francisco have the highest fraction of local independent businesses. You can scan this list to see which cities have a strong local food scene, and which are mostly driven by the national chains.

Must Read

Are we against traffic congestion or more traffic? There’s a provocative essay on substack that questions some basic assumptions about transportation advocacy. The author argues that while its tempting for transit and activte transportation advocates to make common cause with other road users over the supposed scourge of traffic congestion, its ultimately self-defeating.

For those who are concerned about reducing impacts on climate and improving public health in the US, we need to understand that more traffic is bad and congestion is not our problem, and is really our ally. This is sensible only if we distinguish traffic from traffic congestion. If we care about climate and public health, we need to reduce traffic. Traffic congestion might frustrate drivers enough to consider other options.

The underlying problem is our old friend induced travel: steps we take to reduce congestion and improve car travel times inevitably lead to more and longer car trips. And it’s the volume of traffic, not its sometimes slow speed, that is the source of the real negative externalities, including crashes and pollution.

States siphoned millions of dollars in climate money into road building projects. One of the headline features of the Bipartisan Infrastructure Law was a modest allocation of transportation funds to reduce greenhouse gases and mitigate effects of climate change. But the Washington Post reports that thanks to the “flexibility” in federal funding, state highways departments have reallocated millions of this money to other projects, including highway expansions and road-building.

A legal provision predating the infrastructure law allows states to shift up to half of their federal transportation funds among several programs — a provision that also applies to transportation money from the new law. Kevin DeGood, director of the infrastructure program at the left-leaning Center for American Progress, said Congress clearly intended for money to be allocated to projects that would reduce emissions or protect against extreme weather.

“It’s an absolute failure that this is allowed to happen,” he said.

researchers have also found that unclogging roads tends to induce people to drive more, spurring more emissions. Alex Bigazzi, a civil engineering professor at the University of British Columbia who has studied the effects of congestion-reducing technology, said it’s not the most efficient way to cut emissions.

“It’s a stretch to say this is a carbon-reduction strategy,” he said. “Traffic volumes are really the major driver of emissions from transportation systems.”

The reallocation of these funds is part two of an “Empire Strikes Back” effort by the highway lobby. Part one was getting the Federal Highway Administration to roll back administrative guidance directing states to fix existing highways before building new ones.

New Knowledge

Working remotely lowers productivity. The Covid pandemic produced a sea-change in the adoption of work-from-home, and workers, businesses (and housing and office markets) are still digesting the implications. One of the big and largely unsettled questions is whether people working at home are as productive as those working in office settings.

As a practical matter, its difficult to accurately measure worker productivity, and there are many confounding factors that are likely to reach reliable conclusions. One key issue is selection bias: it may be that those who are more productive working at home tend to self-select for these opportunities, so while some workers are as productive, or more productive remotely, that isn’t necessarily true on average, for for everyone.

A new study from India uses a sophisticated random assignment design to overcome this selection bias issue. It studied workers handling a series of easily measured, routine functions which are done similarly in office and remote work settings.

The key finding: On average, those working remotely were 18 percent less productive than their in-office peers. About two-thirds of this difference in productivity manifested itself from the outset of assignment; the remaining increase in productivity was attributed to better/faster learning of skills in an office environment.

While overall in-office workers were more productive, the study noted that selection effects tended to worsen the home/office productivity gap: workers who prefer to work at home, as opposed to those who preferred office locations tended to be less productive at home.

David Atkin, Antoinette Schoar & Sumit Shinde, Working from Home, Worker Sorting and Development, NBER WORKING PAPER 31515, July 2023, DOI 10.3386/w31515

In the news

City Observatory Director Joe Cortright was named one of Planetizen’s 100 most influential contemporary urbanists, clocking in at #56!