What City Observatory did this week

Testifying on the Oregon Transportation Finance. City Observatory director Joe Cortright testified to the Oregon Legislature on HB 2098, a bill being proposed to fund bloated freeway widening projects in the Portland Metropolitan area. As we’ve previously reported at City Observatory, proposed amendments to this bill would give the Oregon Department of Transportation a virtual blank check towards the construction of the multi-billion dollar Interstate Bride Replacement Project and the I-5 Rose Quarter freeway widening. The draft amendments establish a vague and legally dubious statement of legislative “intent” to fund both projects, which on its face seems harmless. But the Oregon Transportation Commission could use those statements of intent, coupled with its broad discretion to borrow funds, to launch both of these multi-billion dollar boondoggles, and present subsequent Legislature’s with a fait accompli—a reprise of the classic Robert Moses strategy of “driving stakes and selling bonds” to lock in freeway construction.

The HB 2098 amendments also propose raiding the state general fund to the tune of $1 billion–breaking down a decades old fiscal firewall that separated road finance from other public expenditures, and is the backbone of the state’s “user pays” policy for transportation.

Links to written testimony submitted to the Joint Transportation Committee are here.

Must Read

Lessons from a century of transit decline. The heyday of American transit was nearly a century ago, and virtually every American city had a robust streetcar network. Bloomberg’s David Zipper interviews Nicholas Dagen Bloom, a professor author of the new book, The Great American Transit Disaster, that chronicles that decline. Bloom argues that the ascendancy of car wasn’t so much the result of conspiracies or some technological inevitability, but conscious (and, at the time, widely supported) policy choices. In the interview, Bloom offers some insights from history that might help us now. In particular, he emphasizes maintaining transit service, and making transit more competitive by catering less to cars.

. . . we should be thinking about maintaining the quality of service for what we now have. Current levels of service could be shredded and ridership shattered as the post-pandemic financial realities sink in. Given that, I don’t know that we should be building any new transit lines at this point.

. . . the compelling case for greater ridership is the aggravation of driving. For that reason, the most positive things might be rezonings, the multifamily boom, and the end of parking minimums. If we remove highways in certain areas, there’s an opportunity for transit to be competitive. But barring that, it’s very hard to know what an agency on its own can do because they’re now in survival mode.

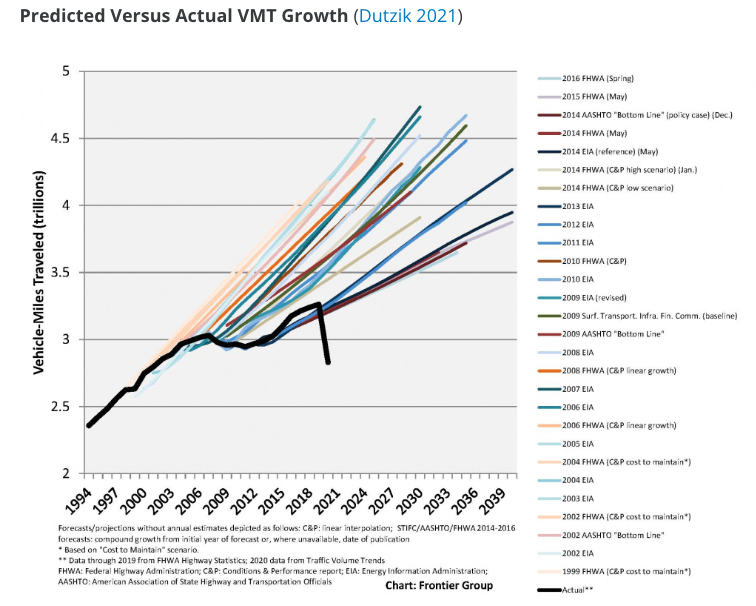

Bad Models, Bad Decisions. The irreplaceable Todd Litman takes a look at the scientific basis of traffic modeling and traffic impact statements, and finds them wanting, with devastating effects. Whether its assumptions about inexorable and unending traffic growth, or fixed (and exaggeratedly high) estimates of traffic generation from new development, planning and engineering decisions are dictated by some dubious statistics. Total vehicle miles traveled in the US have been routinely over-predicted leading to overbuilt highways.

Litman points to this chart from the Frontier Group showing how Department of Transportation and Department of Energy forecasts have consistently over-estimated the growth in driving in the US (forecasts are colored lines; actual is black). With this as their future worldview, it’s little wonder that planning gets biased in favor of accommodating an assumed surge in automobile travel. As Litman writes:

Litman points to this chart from the Frontier Group showing how Department of Transportation and Department of Energy forecasts have consistently over-estimated the growth in driving in the US (forecasts are colored lines; actual is black). With this as their future worldview, it’s little wonder that planning gets biased in favor of accommodating an assumed surge in automobile travel. As Litman writes:

. . . practitioners use demonstrably inaccurate models that often result in inefficient, unfair, and environmentally harmful decisions. In the past, practitioners hid behind their technical expertise, but they are starting to face legal challenges.

Why do transportation agencies spend so much more on automobile infrastructure than other modes, despite their lower total costs and greater benefits? It is partly the fault of practitioners who perpetuate biased planning practices. It is time for reform. Either we create more accurate, comprehensive and multimodal planning practices ourselves, or we will be forced to, by litigation.

Like Litman, we share the hope that policymakers (and courts) will insist on data, models and regulations that are scientifically based and free from implicit biases.

A worthwhile Canadian Initiative: Cancelling a highway tunnel, building a transit tunnel. For decades, Quebec has been contemplating a third highway crossing of of the St. Lawrence River. Though its long been a campaign promise of the incumbent provincial government, in a surprising turnaround, Premier Francois Legault’s government, after a careful scientific review, has ditched plans for the highway tunnel and is now proposing to move forward with a transit-only tunnel as the third crossing. The government’s review concluded, that in the wake of increased work-from-home in the wake of the Covid-21 pandemic traffic growth had attenuated, eliminating the need for the $6.5 billion highway tunnel. Bloated, polluting road projects have always done more to damage urban economies than to bolster them. We can only hope that leaders of US cities will similarly reconsider the wisdom of such projects.

New Knowledge

Has the Covid-21 effect run its course in urban neighborhoods? The Covid-19 pandemic produced some abrupt shifts in population migration patterns within and across US cities. The big question is whether these are short-lived changes that will be quickly reversed to underlying trends, or whether a post-pandemic world will be fundamentally different. Brookings Institution demographer Bill Frey has a readout of the overall county level population trends from the latest US Census data.

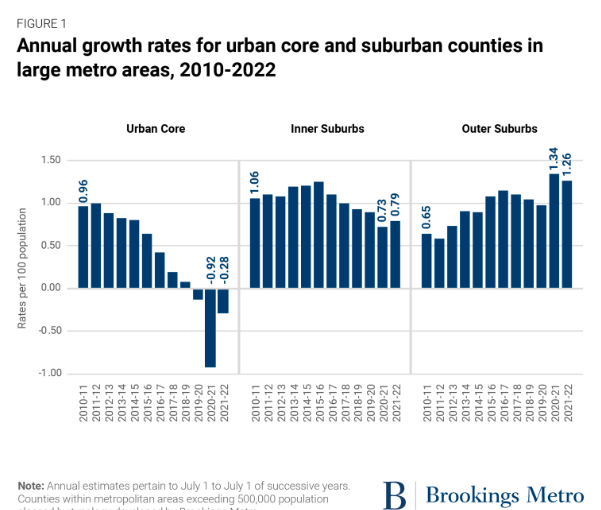

Frey’s work shows that at least some of the decline in the densest, most central US counties has abated or reversed in the latest data. (Brookings uses a typology that classifies metropolitan US counties as either “urban core” or “suburban.” It’s a useful, rough-and-ready way of contrasting urban-suburban trends, but due to the variability of county boundaries, as we’ve noted, its an imperfect way of characterizing what’s happening in city neighborhoods.

Frey’s key finding is that, aggregated across large metro areas, the decline in population in central counties has attenuated. Urban Core counties racked up impressive population gains early in the last decade, but their growth slowed, and was negative in the pandemic year of 2020. The Census data show that decline attenuated sharply in 2021-22.

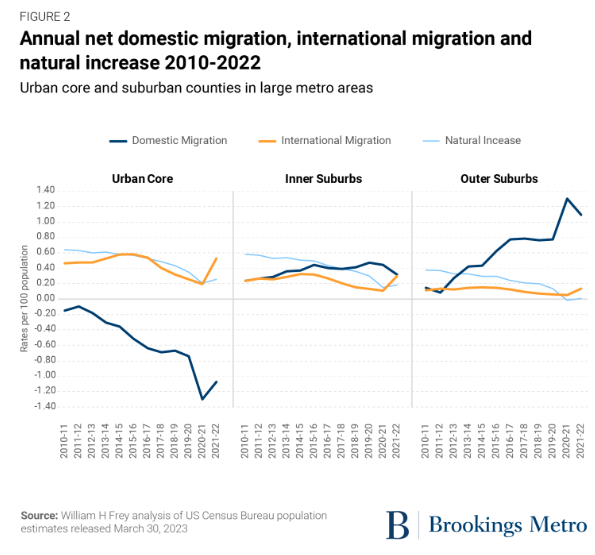

Frey’s work helpful digs into the components of population change across the different county types. Population changes for a variety of reasons: natural increase (the difference between births and deaths), migration to and from other locations in the US, and international immigration. While much of the narrative surrounding the pandemic was a supposed increased in out-migration from urban core areas, a bigger factor in many cases may have been the decline in international immigration (a trend very evident during the Trump years), which was particularly sharp during the pandemic. Urban core counties have traditionally been the biggest magnets for international immigrants, and so they were particularly affected by the decline in international immigration.

The data show that international immigration (the orange line) bounced back in 2022 in every county classification, but was most significant for urban core counties.

William H. Frey, “Pandemic-driven population declines in large urban areas are slowing or reversing, latest census data shows,”

Brookings Institution, April 19, 2023

In the News

BikePortland featured our analysis of proposed legislation in Oregon providing a virtual blank check for two huge freeway expansion projects.