What City Observatory did this week

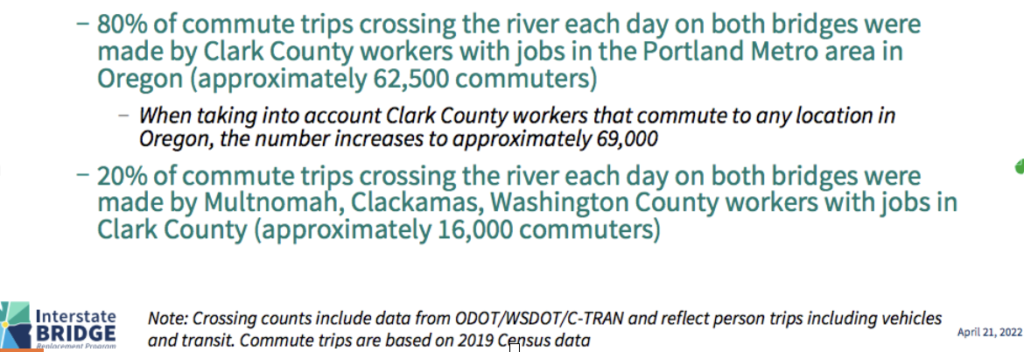

Why should Oregonians subsidize suburban commuters from another state? Oregon is being asked to pay for half of the cost of widening the I-5 Interstate Bridge. Eighty percent of daily commuters, and two-thirds of all traffic on the bridge are Washington residents. On average, these commuters earn more than Portland residents.

The 80/20 rule: When it comes to the I-5 bridge replacement, users will pay for only 20 percent of the cost of the project through tolls. Meanwhile, for the I-205 project in Clackamas County, users—overwhelmingly Oregonians—will pay 80 percent (or more of the cost in tolls). Meanwhile, state legislators are looking—for the first time—to raid the state’s General Fund (which is used to pay for schools, health care, and housing) to pay for roads by subsidizing the Interstate Bridge Replacement Project to the tune of $1 billion. The proposal for Oregon to fund half of the cost of the Interstate Bridge Replacement is a huge subsidy to Washington State commuters and suburban sprawl.

A blank check for the highway lobby. The HB 2098 “-2” amendments are perhaps the most fiscally irresponsible legislation ever to be considered by the Oregon Legislature. They constitute an open-ended promise by the Oregon Legislature to pay however much money it costs to build the $7.5 billion Interstate Bridge Replacement and $1.45 billion Rose Quarter freeway widenings—projects that have experienced multi-billion dollar cost overruns in the past few years, before even a single shovel of dirt has been turned. HB 2098-2 amendments would:

- Raid the Oregon General Fund of $1 billion for road projects

- Give ODOT a blank check for billions of dollars of road spending

- Allow unfettered ODOT borrowing to preclude future Legislatures from changing these projects and forcing their funding

- Eliminate protective sideboards enacted by the Legislature a decade ago

- Enact a meaningless and unenforceable cap on project expenses.

Must Read

Tokyo as an anti-car paradise. In a shortened chapter lifted from his forthcoming book Carmageddon, Economist writer Daniel Knowles digs deep into the reasons why Tokyo excels as a metropolis with high density, affordable rents, great public transit, walkable neighborhoods and relatively few cars. It’s more or less the inverse of the United States: driving and parking are expensive, while density is lightly regulated. Before you can legally register a car in Japan, you have to show that you have an off-street parking space in which to store it, and–shock!–overnight on-street parking is largely illegal. Meanwhile, single family zoning is virtually unknown, and land owners are free to build to pretty much whatever density they’d like in residential areas, which is exactly what the nation’s mostly privately owned railroads have done, building dense housing around new or expanded transit stations. And when it came to building expressways, Japan relied heavily on the free market, letting private companies build and operate tollways, and the tolls, like the limits on parking, make driving an unattractive and expensive alternative. And as Knowles stresses, all this reinforces the rich, and fine grained walkable urbanism of Tokyo neighborhoods. By insisting that cars pay their way, rather than pampering them, people take precedence.

Another freeway widening fail: Just south of San Francisco, authorities have spent half a billion dollars adding more capacity to Highway 101, with predictably disappointing results. Roger Rudick, writing for Streetsblog San Francisco relates the all too common tale of a freeway widening project that hasn’t done anything to reduce congestion. After spending $600 million to widen 14 miles of freeway, one of the project’s private engineering consultants conceded:

“California in general has that problem: that as soon as we start to build something we’re immediately over capacity by the time we finish building it, so it’s almost impossible for us to keep up with the amount of demand,” admitted Monique Fuhrman, Deputy Policy Program Manager with HNTB, which worked on the project, when questioned by Swire at the CAC meeting. She added that traffic levels are already “getting back to the way we were before.”

Local transportation advocate Mike Swire pushed back against the consultants self-congratulatory talking points, challenging Fuhrman to explain why freeway expansion wasn’t simply a never-ending cycle of expansion, induced demand and recurreing congestion. Swire asked:

“At what point do we stop doing something we know isn’t working?”

To which Fuhrman replied:

“That’s like an existential question. I do not know.”

Which is where, for the moment, we leave the absurd situation, though we can be sure there will be another engineer, another widening project, and another sense of existential bafflement (and indifference) when it too, doesn’t relieve congestion.

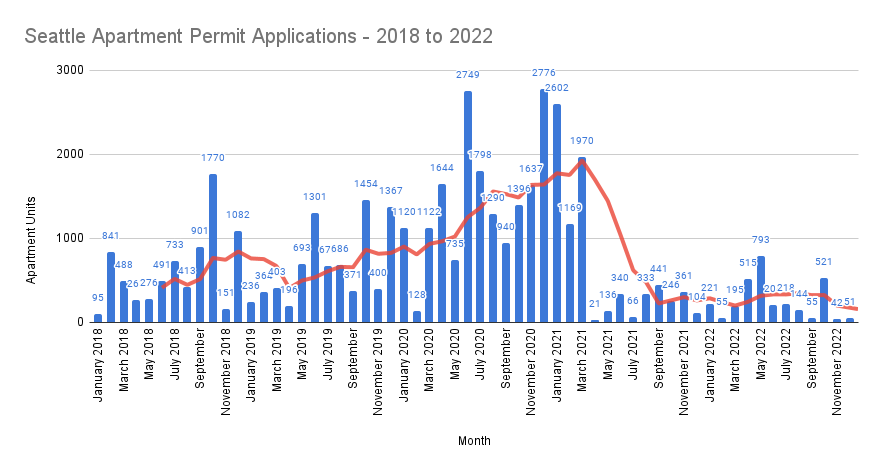

New apartment construction in Seattle is flat-lining: Is mandatory affordable housing to blame? Seattle has been one of the epicenters of rapid urban growth over the past few decades, and growing demand for city living has pushed up housing prices–and apartment rents. A couple of years ago, the city implemented its “Mandatory Housing Affordability” (MHA) program, requiring apartment developers to either set-aside units for low or moderate income households, or make payments into a city housing affordability fund. In effect, these requirements act like a tax on new multi-family housing, and not surprisingly, may discourage development. New statistics published by the Urbanist show a worrying collapse of apartment permits in Seattle:

Since March 2021, shortly after the MHA program was mostly phased in, permit applications dropped sharply from an average of more than 1,500 per month to fewer than 500 per month. We think the city should be watching this closely. If fewer apartments are built now, that’s likely to leader to a tighter housing market in the years ahead, with likely further rent increases.

Since March 2021, shortly after the MHA program was mostly phased in, permit applications dropped sharply from an average of more than 1,500 per month to fewer than 500 per month. We think the city should be watching this closely. If fewer apartments are built now, that’s likely to leader to a tighter housing market in the years ahead, with likely further rent increases.

The State of Play: How highway agencies co-opt and debase progressive policies

In last week’s Week Observed, we highlighted a provocative article from Chuck Marohn of Strong Towns, illustrating how a highway project in Maryland had effectively co-opted the “Complete Streets” moniker for a project that remained a dangerous (even deadly) car-dominated “stroad.” Chuck made the very good point that engineers and highway departments will deftly borrow and trade on progressive sounding terminology. That part of Marohn’s critique is valid. But Marohn—and by dint of repetition—City Observatory may have conveyed the impression that the originators of the complete streets concept are somehow to blame. As our friends, Stephen Davis and Beth Osbourne of Smart Growth America have offered a spirited defense of the efforts of the National Complete Streets Coalition. They point out that the Coalition doesn’t merely promote the concept, but also evaluates the effectiveness of adopted policies, develops champions, highlights best practices and generates constant national attention through reports like Dangerous by Design. Ultimately, Davis and Osborne agree with Marohn that there’s an entrenched status quo that’s adept at appropriating and diluting progressive concepts. They argue that means the diverse advocates for change need to make common cause against this co-opting,

Going forward, we all need to keep our attention squarely focused on the transportation agencies and engineers who prioritize speed above all else and call it safety, who do the same old thing and call it something new, who build dangerous streets and call them complete.

That’s going to be a never-ending task: There’s no shortage of consultants, public relations, marketing and branding types that will–for a generous fee–help legacy highway agencies re-brand their work as green, equitable, safety-conscious and net zero carbon. Its vastly easier to feign those values in awards and press releases than it is to accomplish meaningful change in the real world. Ultimately, we have to insist on measurable results—fewer people killed and injured, less greenhouse gases emitted, more people living in walkable, bikeable communities, with a full range of transportation choices.