What City Observatory did this week

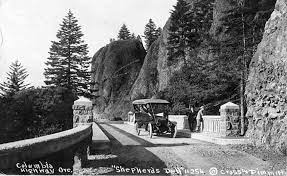

Oregon crosses the road-pricing Rubicon. Starting this spring, motorists will pay a $2 toll to drive Oregon’s historical Columbia River Gorge Highway. Instead of widening the road, ODOT will use pricing to limit demand. This shows Oregon can quickly implement road pricing on existing roads under current law without a cumbersome environmental review or equity analysis.

For more than a decade, the agency has been dragging its feet in implementing road pricing, complaining it didn’t have the authority, or had to undertake lengthy processes first. Tolling the old Columbia River Highway shows that instead of widening roads, the agency can use pricing to reduce congestion and make the transportation system work better. Perhaps this will be the breakthrough that will lead ODOT to deploy pricing elsewhere.

Must read

Cincinnati will have the best bridge that somebody else will pay for. For some years, Southern Ohio and Northern Kentucky residents have been complaining about traffic on the Brent Spence Bridge, which carries two interstate highways across the Ohio River. While many say they want a big new bridge that would almost triple the capacity of the existing structure, neither state has ever found the money.

Now, thanks to the IIJA, the two state’s are hoping that even though they don’t think it’s worth the expense that the federal government will foot the bill.The two states are hoping federal grants will allow them to build the multi-billion dollar bridge without having to charge tolls to the people who actually use it. As the Kevin DeGood of the Center for American Progress tweeted: “A bridge project that’s so important two states agreed it will only get built if Washington pays for it.”

The high price of electric vehicles. In yet another record-setting round of corporate subsidies, the state of Michigan is paying General Motors to set up electric vehicle manufacturing operations. The Guardian reports GM is slated to get $1 billion in state subsides. The company has promised some 4,000 jobs—which works out to a stupendous $310,000 per job, but that’s almost certainly an under-estimate of the true cost. Job creation counts have routinely been over-promised and under-delivered, and even when automakers have failed in the past to deliver promised jobs, they’ve largely gotten to keep all the subsidies. It’s ironic in a time of record high profits and record low unemployment that state’s are still easy prey for industrial location blackmail.

New Knowledge

Why going faster doesn’t save us any time. Central to the economic analysis of transportation projects is the “value of travel time”—an estimate of what potential travel time savings are worth to travelers. In theory—and thanks to the fundamental law of road congestion, it is way too often just a theory—road investment projects produce economic value because they reduce the amount of time people have to travel to make a particular trip. But the notion is that a roadway or other transportation system investment that enables us to move faster (more speed) allows us to complete any given trip in less time, and that we can count the value of that time savings as an economic benefit of the transportation project. (Which is what is commonly done in the benefit-cost studies done to justify roadway improvement projects).

The trouble is there’s no evidence that increased speed gives us additional time that we then devote to other non-transport purposes. Going faster doesn’t give us more time. It turns out that we don’t use increased travel speeds to get more time to do other things, we simply end up traveling further and not gaining any additional time for other valuable activities, whether work or leisure:

. . . studies on travel time spending find that the average time persons spend on travelling is rather constant despite widely differing transportation infrastructures, geographies, cultures, and per capita income levels. The invariance of travel time is observed from both cross-sectional data and panel data. It suggests that people will not adapt their time allocation when the speed of the transport system changes.

Instead, increased speed of transportation systems is associated with more decentralized land use patterns and longer trips, and all of the supposed “benefit” of increased speed is consumed, in iatrogenic fashion, by the transportation system. And, importantly, changes in speed trigger changes in land use patterns that can diminish proximity to key destinations:

The higher speed enticed residents of small settlements to shift for their daily shopping from the local shop to the more distant supermarket . . . As a consequence, local shops might not survive, forcing both car owners and others to travel to the city for shopping. The impact of the speed increase is in this case a concentration of shopping facilities, implying a decrease of proximity. The positive impact on accessibility is at least partly reversed by the negative impact on proximity, and the outcome for access is undefined. For those who did not use a car and did not benefit from the speed increase, the result was an unambiguous decrease of the access.

This study suggests that the principal supposed economic benefit of transportation investments–time savings–is an illusion. Coupled with growing evidence that higher speeds have significant social and environmental costs (lower safety, health effects, and environmental degradation) this suggests that a reappraisal of transport policies is needed.

Cornelis Dirk van Goeverden, “The value of travel speed” Transportation Research Interdisciplinary Perspectives, Volume 13, March 2022. https://www.sciencedirect.com/science/article/pii/S2590198221002359

Hat tip to SSTI for flagging this research.