What City Observatory did this week

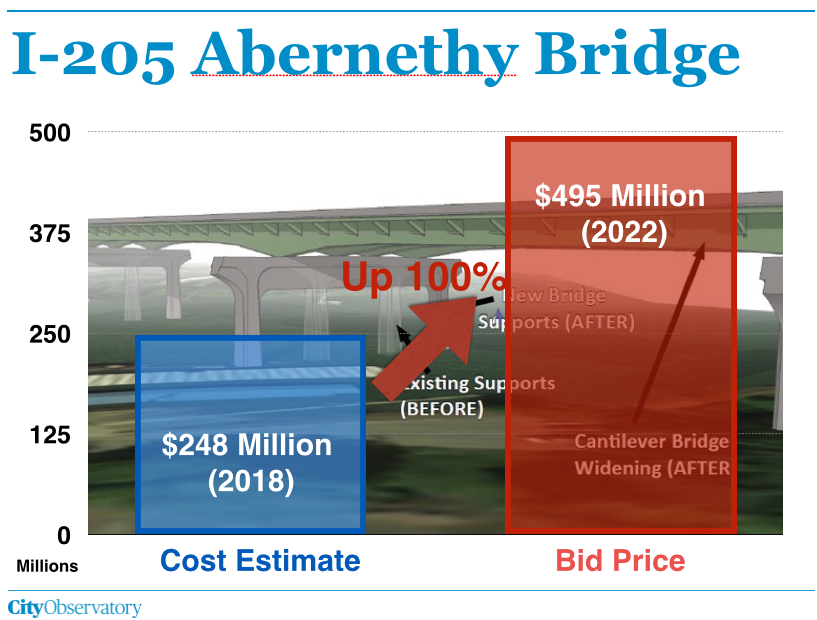

Oregon DOT’s “reign of error”—chronic cost overruns on highway projects. The Oregon Department of Transportation is moving forward with a multi-billion dollar freeway expansion plan in Portland. That poses a huge risk to state finances because the agency has a demonstrated track record of cost overruns. We show that virtually all of ODOT’s biggest projects have experienced cost overruns of more than 100 percent.

ODOT is compounding the financial risk by proposing to issue toll-backed bonds to pay for these projects, and the agency has no current experience in planning, financing or operating tolled facilities. The agency has also failed to acknowledge its record of huge cost-overruns; even a management audit by McKinsey and company designed to address the problem had a 3x cost overrun, and conspicuously excluded ODOT’s most expensive project (and biggest cost overrun) from its analysis.

Must read

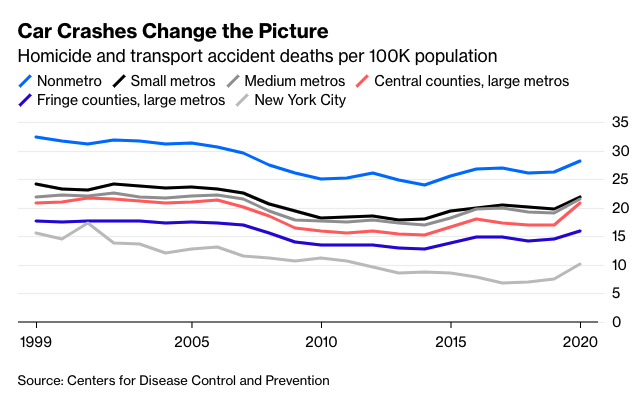

The safest place to live is . . . a big city. Bloomberg’s Justin Fox tackles head on the popular myth that life in big cities is somehow more dangerous that in suburbs or smaller towns. Regardless of what you see or hear in the media, big cities are safer than one or two decades ago; New York City has a very low murder rate. And when you include statistics on automobile crash deaths, cities look even safer. Here’s Fox’s data showing death rates per 100,000 for different places.

The key finding here is that overall death rates from murders and car crashes are no higher in the central counties of large metro areas (the red line) than they are in non-metro, small metro and medium metro areas. And strikingly, the death rate in New York City (the gray line at the bottom of the chart) is markedly lower than anywhere else, a trend that persists even in Covid pandemic. The data suggest it’s time to reconsider the common belief that big cities are somehow more dangerous: they aren’t.

Bringing back single room occupancy buildings. Through much of our history, a boarding houses and rented rooms were a major part of the housing stock, especially for single persons of modest means. But for decades cities have been restricting, prohibiting or even demolishing single room occupancy (SRO) dwellings, partly out of concern for often unpleasant or unhealthy living conditions, but perhaps just as much as yet another form of exclusionary zoning (eliminating or keeping way poor persons by prohibiting housing they can afford. Jake Blumgart writes at Governing about Philadelphia’s effort to re-legalize SRO housing in more places throughout the city. It’s actually a modest proposal, just legalizing SRO’s in multi-family and commercial zones, not the city’s single-family districts. But even that has prompted resistance, with Councilors in some Philadelphia wards seeking to continue to ban SRO’s in their neighborhoods:

District councilmembers represent specific swathes of the city and tend to be most responsive to neighborhood associations and homeowner groups. In a city like Philadelphia, owning a home and car doesn’t mean you are rich by any means, but you have more than many of your neighbors, you are more likely to vote, and more likely to have your voice heard. That voice is likely to express a desire for other single-family neighbors, not rooming houses. Multiple council sources have told Governing that three district councilmembers planned to introduce amendments to Green’s bill that would carve their neighborhoods out of his legislation.

Decent, if modest, housing is clearly preferable to living on the streets, but as with so much of our housing crisis, our wounds are self-inflicted, and amplified by our catering to NIMBY tendencies.

Stop requiring parking everywhere. New York Times columnist Farhad Manjoo channels his inner Don Shoup in this column, making the case that parking requirements are inimical to building the kind of affordable, livable and sustainable urban neighborhoods we most desire. It’s an oft-told story, but Manjoo makes it clear:

. . . by requiring parking spaces at every house, office and shopping mall — while not also requiring new bike lanes or bus routes or train stations near every major development — urban-planning rules give drivers an advantage in cost and convenience over every other way of getting around town. . . . There are other ways parking wrecks the urban fabric. It creates its own sprawl— the more endless, often empty parking lots between businesses, the less walkable and more car-dependent the city becomes. And requiring parking worsens inequality. Because people whose income is less tend to drive less and use transit more, they’re essentially being forced to pay for infrastructure they don’t need — while wealthier car drivers get a break on the true costs of their car habit.

New Knowledge

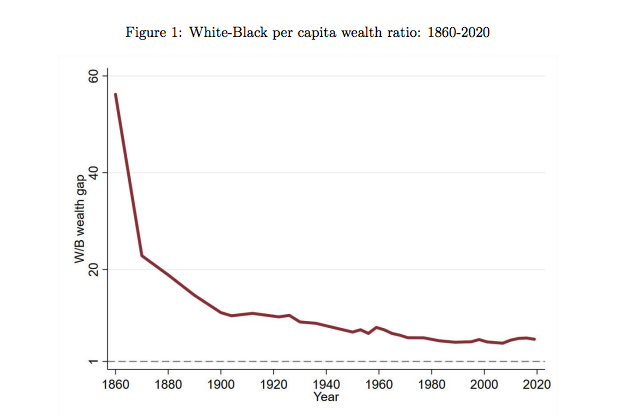

The persistent of the racial wealth gap. Few economic facts are as stark and enduring than the gap in wealth between Black and white US households. A new study published by the National Bureau of Economic Research provides a detailed historical record of wealth trends that illustrates how wide–and intractable–the wealth gap has become.

The end of slavery, thanks to the Emancipation Proclamation eliminated the single biggest obstacle to Black wealth, and had immediate an important effects. Black wealth, which was negligible in relation to typical white household wealth gained substantially in the first few decades after Emancipation. But the pace of those gains slowed dramatically. Between 1860 and 1900, the gap between Black and white wealth fell from a factor of 50 to about a factor of ten. Since then the pace of improvement has been muted. Black wealth has converged on white wealth, but only slowly and since 1980, there’s been little change in the disparity.

The paper’s analysis shows that differential wealth holdings and capital gains play an important role in maintaining the racial wealth gap. White households, as a group, own more equities, and enjoy higher average returns, meaning that the wealth gap declines slowly if at all.

. . . as the racial wealth gap decreases, convergence slows and differences in returns on wealth and savings begin to matter more for the shape of convergence. Given existing differences in the wealth-accumulating conditions for white and Black individuals, our analysis suggests that full wealth convergence is still an extremely distant or even unattainable scenario. Furthermore, rising asset prices have become an important driver of racial wealth inequality in recent decades. The average white household holds a significant share of their wealth in equity and has therefore benefited from booming stock prices while the average Black household, for whom housing continues to be the most important asset, has been largely left out of these gains.

Given the overall increase in inequality in US wealth in the past few decades, the author’s predict that there is likely to be little improvement in the racial wealth gap. Absent some significant changes in public policy (regarding either the tax treatment of capital gains, or reparations), the Black-white wealth gap is likely to diverge in the future.

Ellora Derenoncourt, Chi Hyun Kim, Moritz Kuhn & Moritz Schularick, Wealth of Two Nations: The U.S. Racial Wealth Gap, 1860-2020, NBER Working Paper 30101, June 2022.