What City Observatory did this week

Failing to learn from the failure of the Columbia River Crossing. Last week, Portland’s Metro Council voted 6-1 to wave on the Oregon Department of Transportation’s plan for a multi-billion dollar freeway widening project branded as a bridge replacement. In doing so, the Council is ignoring the lessons of the project’s decade-old doppelganger, the failed Columbia River Crossing.

In this commentary, then-Metro President David Bragdon explains how the Oregon and Washington highway departments systematically lied to and misled regional officials to advance the project, something they’re repeating chapter and verse again to sell the “Interstate Bridge Replacement Project.” Those who don’t learn from the mistakes of of history are condemned to repeat them.

Must read

Killing the Smart City. Was there any idea more overwrought than the Google-backed Sidewalk Labs plan to turn Quayside—part of Toronto’s waterfront—into a tech-laden “Smart City?” After years of hype, millions spent on plans of questionable merit on the turgid and non-sensical promise of “building a city from the Internet up,” the project collapsed of its own weight in 2020. It predictably blamed the pandemic, but that’s not the real story. Writing at the Technology Review, Karrie Jacobs diagnoses our fascination with—and the flaws of—these sweeping top-down visions of how urban areas are transformed. Sidewalk Labs smart city plans had the conceit that it was new and better technology that was the key to cities improving, rather than building a better place for people.

The real problem is that with their emphasis on the optimization of everything, smart cities seem designed to eradicate the very thing that makes cities wonderful. New York and Rome and Cairo (and Toronto) are not great cities because they’re efficient: people are attracted to the messiness, to the compelling and serendipitous interactions within a wildly diverse mix of people living in close proximity. But proponents of the smart city embraced instead the idea of the city as something to be quantified and controlled.

We’ve made this mistake before: The story of twentieth century urbanism was conforming cities to the latest technology—the private automobile. That tech-led approach to development has ravaged cities and damaged the planet; Toronto, and the rest of us were lucky that Sidewalk Labs effort failed.

External costs. Climate change is, without doubt, the most global crisis humanity has ever confronted. Our standard way of thinking about the costs and benefits, which focuses on individuals, neighborhoods, communities, and occasionally nations, misses the fact that the environmental consequences of our decisions are profoundly global, and not local. Climate change is real to us when we see the effects locally, as when last summer, temperatures in Portland hit 117 degrees. What that insular perspective misses is that the cumulative effects of climate change are larger and more widespread than any of us individually experience. A new study puts some numbers to this idea. It estimates that the global cost of US carbon emissions is $1.9 trillion over the past quarter century.

Rising renter incomes and higher rents. There’s no question that our constrained housing supply (especially in cities) plays a key role in causing housing affordability problems. But housing prices and rents are driven by both supply and demand. One of the key elements of demand is household incomes, and in the past couple of years, rising incomes have helped push up rents. While housing discourse focuses on low and moderate income renters who are cost burdened, its the case that incomes have risen substantially for households renting market rate housing. And if your income goes up, you are able, and might be willing to bid more for housing. A new study from RealPage suggests that’s exactly what is happening:

Between 2016 and 2019, market-rate apartment renter incomes climbed around 4.5% annually up to a high of $66,250 in 2019. Incomes among lease signers then dropped 1.9% in 2020 due to the pandemic before surging up 7.7% in 2021 and another 7.1% so far in 2022 up to a new high of $75,000.

RealPage’s study aligns with previously published research from Harvard’s Joint Center for Housing Studies, which showed the majority of net new renter households over the last decade had incomes above $75,000.

What makes the pandemic-era results al the more remarkable is the sheer volume of renters coming in with higher incomes. Roughly 1 million net new households entered the professionally managed, market-rate apartment sector since the start of 2020 – the biggest wave of demand in RealPage’s three decades of tracking apartments. Those numbers are even more impressive given that they occurred at the same time demand flowed heavily into for-sale homes and single-family rentals, as well.

These data don’t mean that housing affordability isn’t a problem, in fact, just the opposite: the fact that well off households have more income, and more such households are bidding for apartments means that those with lower incomes face even greater competition (and therefore, higher rents) in the marketplace. Ultimately, the policy solution has a lot to do with supply, and importantly, more supply at every tier of the marketplace, because if the demand of higher income households isn’t met by new construction, they’re likely to further bid up prices of existing housing.

New Knowledge

Estimating the size of our housing production deficit. Up for Growth has an ambitious new report attempting to comprehensively measure the nation’s shortage of housing, suggest policy solutions for increasing housing supply and estimating economic, social and environmental benefits of doing so.

The report estimates that nationally, we’ve “underproduced” about 3.8 million housing units. And the report offers a reasonable set of estimates of how big a housing gap there is in each state and large metropolitan area. That’s a valuable insight, but as the report makes clear, this isn’t just simply about producing more housing units in the aggregate: we need more housing in the high opportunity locations that would enable people to advance economically and live more sustainably.

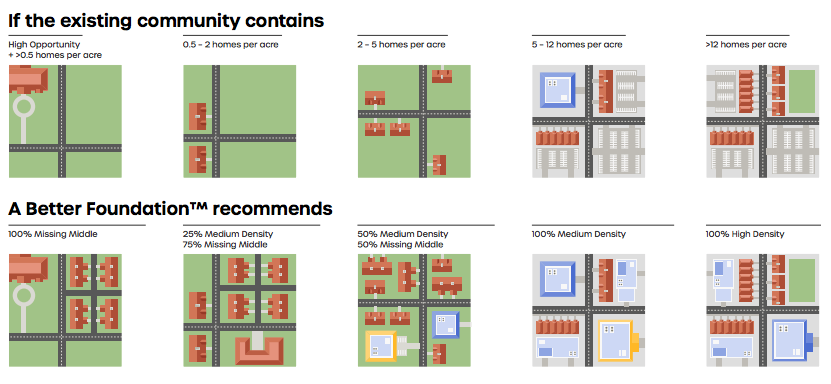

The report sketches out a “new foundation” for growth that targets a graduated series of infill development strategies for different communities and neighborhoods. It recommends that new housing development be focused in neighborhoods with high levels of economic opportunity, that are job-rich and housing poor, and that have adequate infrastructure (indicated in part by high levels of walkability). The report identifies census tracts that meet these criteria. It recommends density increases based on the current development pattern of an area: “missing middle” housing in low density single family areas; low- or mid-rise apartments in somewhat denser areas, and high rises in the densest neighborhoods.

The Housing Underproduction Report also makes key connections to equity, social justice and sustainability and housing supply: many of our worst social problems (racial wealth disparities and limited intergenerational economic mobility) stem, at least in part, from constraints on housing supply. Overcoming housing underproduction is a key strategy for rectifying these disparities.

More of the same housing policy drives poor climate outcomes. We intentionally designed A Better Foundation to realize tangible climate benefits while increasing housing availability and affordability. Key to this framework is locating new housing in areas with high concentrations of jobs and community assets, and in walkable neighborhoods with generous pedestrian or transit infrastructure. This method increases land efficiency, lowers vehicle miles traveled, and decreases the social cost of carbon.

And the “better foundation” pattern of economic growth pays economic and fiscal dividends as well. More intensive infill development reduces the need for expensive infrastructure investment, and lowers housing and transportation costs (more supply can be expected to reduce housing costs; more concentrated development will reduce vehicle miles traveled).