What City Observatory did this week

What does equity mean when we have a caste-based transportation system? Transportation and planning debates around the country increasingly ponder how we rectify long-standing inequities in transportation access that have disadvantaged the poor and people of color. In Oregon, the Department of Transportation has an elaborate “equitable mobility” effort as part of its analysis of tolling. And Portland’s Metro similarly is reviewing transportation trends to see how they differentially affect historically disempowered groups.

This discussion is fine, and long overdue, but for the most part ignores the equity elephant in the room: America’s two-caste transportation system. We have one transportation system for those wealthy and able enough to own and drive a car, and another, entirely inferior transportation system for those too young, too old, too infirm or too poor to be able to either own or drive a private vehicle. There are other manifest inequities in the transportation system, but most of them stem from, or are amplified by this two-caste system.

Those in the lower-caste face dramatically longer travel times, less accessibility to jobs, parks, schools, and amenities, and face dramatically greater risk in traveling than those in the privileged caste. In a policy memorandum to Portland’s Metro regional government, we’ve highlighted the role of the caste system, and pointed out that its virtually impossible to meaningfully improve equity without addressing this divide.

Must read

The look of gentrification. One of the chief criticisms of gentrification is aesthetic: Supposedly new buildings or new businesses both symbolize and cause gentrification. A fancy coffee shop, a new apartment block. But Darrell Owen challenges the notion that these symbols tell us much about the causes, and even less about the cures, for gentrification.

As Owens argues, the cause of gentrification is the increased demand for housing in what were formerly disinvested neighborhoods, coupled with the tendency of new arrivals to insist on “status quo-ism”–trying to keep things from changing. It’s tempting to paint particular people or buildings as victims, but this misses the underlying causes:

Caricatures like skinny white bike bros or some scooter make convenient distractions away from the longstanding unaffordability that the original gentrifiers often created. Many of the first wave gentrifiers had consumed existing housing back when it was cheap, then made it impossible to add more housing to mitigate additional residents like themselves, thus increasing displacement onto incumbents. Bernal, the Haight, South Berkeley, North Oakland—all these neighborhoods experienced this. “I’m the good one,” the first-wave gentrifier insists. “The neighborhood gentrified only after I got here.” No, the neighborhood gentrified because you got here.

To Owens, the gentrification occurs because of the limits imposed on the construction of new housing: It isn’t the new buildings that cause gentrification, it’s the ban on new buildings that has the effect of driving up prices and displacing long-time residents.

Those who fought attempts to grow the housing capacity of our old neighborhood got what they wanted: all the same old houses, parks and stores. But at the expense of the people who had lived there in the first place by trading them for new arrivals. Population growth does not require displacement when you prioritize making space rather than the aesthetic of buildings.

A rural reality check on remote work. The increasingly wide adoption of remote work in the wake of the Covid pandemic has given rise to renewed prognostications that rural economies will be buoyed by an influx of talented workers from cities. Writing at Cardinal News, Dwayne Yancey offers a reality check and some cautions. A first important bit of context is acknowledging that the population decline in rural America is deep-seated and long-lived: rural counties are older, deaths outnumber births, and much of this is baked in the demographic cake. While migration is benefiting some rural areas, it tends to be those places with high levels of amenities, and formerly rural counties that have become de facto exurbs by virtue of proximity to strong metro areas. Also working against a general rural rebound is the continuing decline in the number of Americans who move each year–a trend which continued during the pandemic. Finally, there’s the issue of “The Big Sort”–Bill Bishop’s term for the increasing tendency of migrants to choose to move to communities where people share their interests. Migrants from predominately blue cities will tend to gravitate to those communities that echo their values, a finding highlighted in a recent Redfin survey. As Yancey concludes:

This Redfin report raises the question of whether left-leaning office workers are going to want to pick up their computers and move to conservative areas. If not, then that greatly reduces the opportunities for those conservative rural areas to benefit from any migration of remote workers. Maybe only the conservatives will relocate and maybe that will be enough, maybe more than enough, to make a difference demographically.

New Knowledge

Racial discrimination in renting. It’s long been the case that Black and Brown Americans have faced discrimination in rental housing markets. A new study measures discrimination in large metro areas.

The study tests for discrimination by sending landlords inquiries about potential rental apartments using fictional applicant names that are highly correlated with White, African-American or Hispanic identities. For example, the survey sent out inquiries identified as being from Shanice Thomas, Pedro Sanchez, and Erica Cox among others. The study randomly sent more than 25,000 inquiries to property managers, and tallied the rate of responses by racial/ethnic identification in 50 metro areas across the country.

Overall, the study found that those with potential renters with identifiably African-American or Hispanic names were less likely to receive a response from a property manager than those with identifiably White names. African-American names were about 5.6 percent less likely to receive a response; Hispanic names were about 2.7 percent less likely to receive a response.

The study stratified its findings by city, so its possible to compare the degree of discrimination by region and metropolitan area. Overall, the study found that discrimination was more widespread in the Northeast and Midwest, and tended to be lower in the West. It also found that there was a correlation between racial/ethnic segregation and discrimination: Metros with higher levels of segregation tended to have higher levels of measured rental discrimination against Black and Brown applicants.

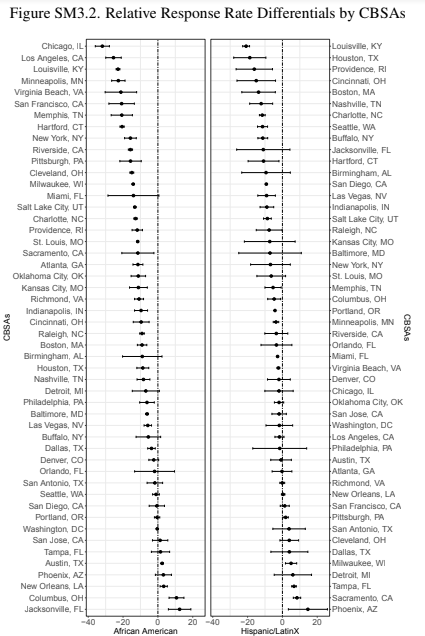

The study ranks metropolitan areas by discrimination (as measured by differential response rates). The following chart shows the response rate differential for African-Americans (left column) and Hispanics (right column), ranked from highest (most discrimination) to lowest. The horizontal lines on the chart are the 90 percent confidence interval of the estimated differential for each metro area; lines intersecting the zero vertical line are not significantly different from zero.

Chicago, Los Angeles and Louisville have the highest levels of disparity for Black respondents; New Orleans, Columbus and Jacksonville have the lowest. Louisville, Houston, and Providence have the most discrimination against Hispanics; Phoenix, Sacramento and Tampa have the least. Interestingly, the authors report that there is very little correlation between discrimination against Black as opposed to Hispanic applicants at the Metro level. This suggests that local market factors may be at work.

Chicago, Los Angeles and Louisville have the highest levels of disparity for Black respondents; New Orleans, Columbus and Jacksonville have the lowest. Louisville, Houston, and Providence have the most discrimination against Hispanics; Phoenix, Sacramento and Tampa have the least. Interestingly, the authors report that there is very little correlation between discrimination against Black as opposed to Hispanic applicants at the Metro level. This suggests that local market factors may be at work.

Peter Christensen, Ignacio Sarmiento-Barbieri & Christopher Timmins, Racial Discrimination and Housing Outcomes in the United States Rental Market, NBER WORKING PAPER 29516. DOI 10.3386/w29516