What City Observatory did this week

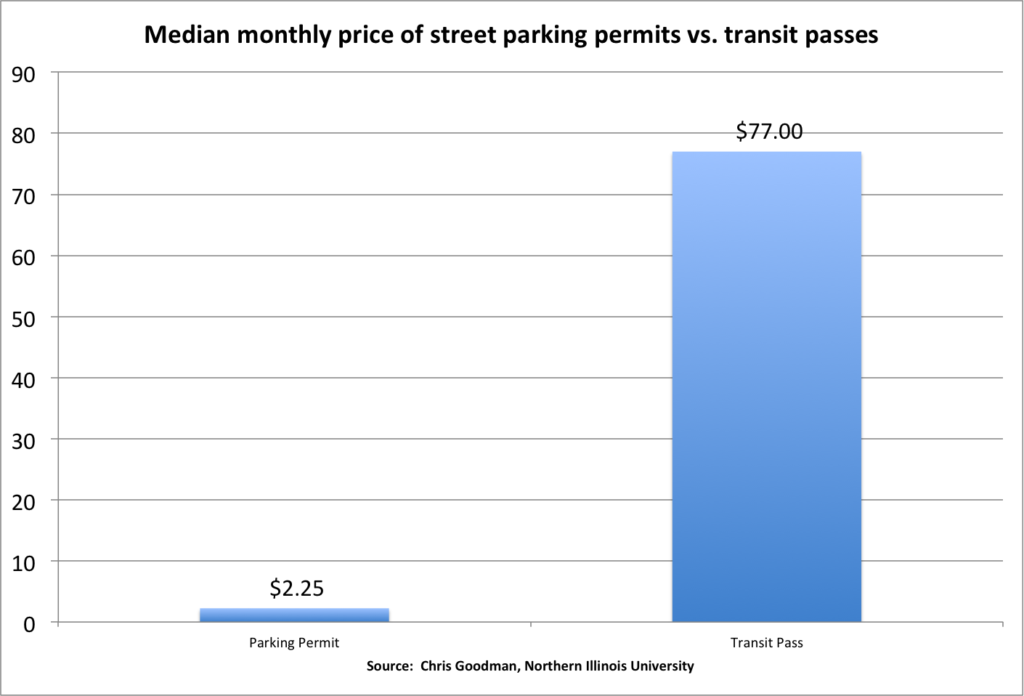

1. Why free parking is one of the most inequitable aspect of our transportation system. There’s a lot of well-founded anger over the inequitable aspects of transportation: the burdens of policing, fare enforcement, and road crashes all fall disproportionately on low income households and communities of color. But a little recognized and pervasive inequity in transportation is the fact that we charge people vastly more for using transit than we do for parking. Data compiled by Northern Illinois University’s Chris Goodman show that most cities charge their residents 20 or 30 times a much for a monthly transit pass as they do for a monthly street parking permit (when they charge anything at all). That makes no sense from an efficiency or equity standpoint. Those who own cars have higher incomes than those who use (and who depend on transit). Private car storage in the public right of way is the conversion of common wealth to private use without compensation, and those who park on-street deprive other users of the potential ouse of that space. In contrast, public transit systems provide significant social benefits (less pollution and congestion), and usually have excess capacity. It makes no sense to charge little or nothing for parking, and too much for transit.

2. How to make gentrification worse. Banning new construction is a great way to push up home values and accelerate gentrification. Cities are conflicted and confused about how to protect affordability. “Stop the world – I want to get off” was the title of Anthony Newley’s 1961 musical, but it seems like the core policy vision of a growing number of urban leaders faced with gentrification. An article earlier this month in the Washington Post portrayed building moratoriums put in place in Atlanta and Chicago in order to fend off gentrification. These efforts are certain to backfire. Blocking new development in the face of growing demand for urban space ironically plays into the hands of speculators and flippers by driving up the value of existing housing. In the face of a shortage of great urban spaces, cities need to look for ways to accomodate more people, of all income groups, not simply to block change.

Must read

This week’s must read articles are a reminder of the important political dynamics that surround land use decision-making and the challenges of balancing local interests with broad public concerns like job creation and housing affordability.

1. Why state action is essential to reform local land use laws. Sightline Institute’s Michael Andersen reflects on some of the key policy (and political) lessons from Oregon’s legalization of multi-plex housing in the state’s single family zones. A first key point is that state action helped get the ball rolling: It’s always difficult in a single neighborhood or city to agree to additional development (see below); up-zoning is the classic prisoner’s dilemma. Having a state step in and require every city to allow a range of housing types overcomes this problem. The second point Andersen makes is a subtle, and seldom recognized one: creating a bias for action. The biggest obstacle to reform, Andersen notes is the inertia of the status quo. Once the state sets a deadline for change it shifts the discussion from whether to do things differently, to a more productive question about what change makes the most sense.

2. NIMBY’s triumphant in NYC. The New York Times reports that a major redevelopment project in Brooklyn’s Industry City is dead, thanks to local opposition, based on concerns about, among other things, gentrification. The Industry City proposal involved redeveloping part of Brooklyn’s waterfront for, among other things, as many as 20,000 new jobs.

3. Ending member privilege. Brandon Fuller ties the demise of the Industry City proposal to a widely shared feature of many local land use processes: “aldermanic privilege.” In cities that elect council members by single member districts, there’s frequently a formal or informal practice of granting individual councilors veto power over land use approvals in “their” districts. A series of studies has shown that cities which have such single member districts systematically allow less housing, and in particular fewer apartments, than cities that don’t have this system. Single member districts escalate the political significance of parochial concerns, and City Councilor’s are often under tremendous pressure to protect “their” neighborhood from adverse effects. Multiplied across a city, that’s a recipe for NIMBYism.

In the News

City Observatory Director Joe Cortright is quoted in The Oregonian’s insightful article on following up on a predicted carmaggedon in Portland. Half of a major interstate bridge was closed for a week, and despite predictions of gridlock, things were actually fine.

Streetsblog republished our commentary on equity and subsidized private car storage in the public right of way as “It Shouldn’t Cost 31x More To Take Transit Than Park.”