What City Observatory did this week

The case against Metro’s $5 billion transportation bond. Portland’s regional government, Metro, is asking voters to approve a $5 billion package of transportation improvements, to be funded by borrowing against an increase in payroll taxes. We take a close look at the proposal, and conclude that its a bad deal on a number of grounds: It emphasizes investments in corridors, mostly highway corridors, rather than on bolstering the dense, walkable centers the region’s transportation plan has emphasized for years.

By the agency’s own estimates, it does virtually nothing to reduce greenhouse gas emissions, even though increased driving is the single biggest source of carbon pollution in Portland. By paying for road improvements with a payroll tax, rather than a user fee, like the gas tax, it implicitly subsidizes driving, with the result that the proposal both insulates drivers from facing the costs of their decisions, and leads to more driving, pollution and crashes. We estimate that the subsidy to driving offsets by a factor of 50 the gains Metro claims from lower carbon emissions from its $5 billion investment package.

Must read

1. Jerry Seinfeld explains why New York (and other cities) aren’t “over.” A New York comedy club owner has picked up and moved to Florida, but not before leaving a trash-talking note for his former city. Jerry Seinfeld takes offense, and explains why leaving the city says more about the club owner than the city. New York, and other cities will thrive, Seinfeld argues, for the same reasons they always have. We won’t all be decamping to the suburbs or rural America and “zooming it in.”

There’s some other stupid thing in the article about “bandwidth” and how New York is over because everybody will “remote everything.” Guess what: Everyone hates to do this. Everyone. Hates.

You know why? There’s no energy.

Energy, attitude and personality cannot be “remoted” through even the best fiber optic lines. That’s the whole reason many of us moved to New York in the first place.

You ever wonder why Silicon Valley even exists? I have always wondered, why do these people all live and work in that location? They have all this insane technology; why don’t they all just spread out wherever they want to be and connect with their devices? Because it doesn’t work, that’s why.

Real, live, inspiring human energy exists when we coagulate together in crazy places like New York City.

It’s an entertaining but well informed argument about why cities matter, and why they’ll persist even in a post-Covid world.

2. How biased traffic models enshrine highway expansion. Vice’s Aaron Gordon has a detailed article illustrating how state highway departments have used biased transportation modeling to justify ever wider roads and freeways. Drawing on examples like Louisville’s massively overbuilt Ohio River Bridges project, Gordon shows that state highway agencies developed multiple, conflicting forecasts, exaggerated ones to justify building the project, more accurate ones to sell bonds.

As Gordon explains, the problems with the “four-step” models have been well-documented for decades, but they continue to be used because they’re structured in a way that can be used to produce just the answers that State DOTs want: Build baby, build. As we’ve noted at City Observatory, these models routinely overestimate future traffic and overstate congestion in a “No-build” world, and that at best they become self-fulfilling prophecies, where building additional road capacity induces additional travel and congestion that wouldn’t have occurred if the project hadn’t been built.

As Transportation for America’s Beth Osborne trenchantly observes highway builders use the models conceal who’s making the decision:

“This is the fundamental problem with transportation modeling and the way it’s used. We think the model is giving us the answer. That’s irresponsible. Nothing gives us the answer. We give us the answer.”

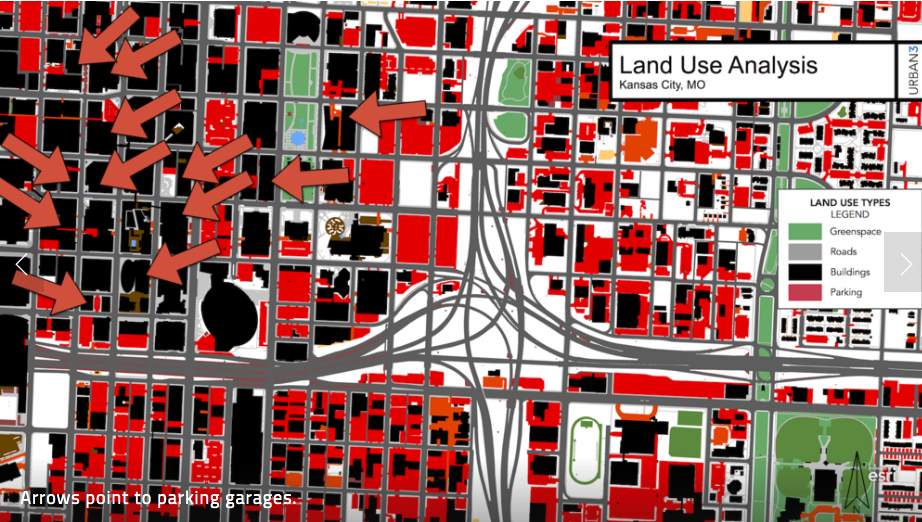

3. Parking’s dominance of Kansas City. When you look closely, its astonishing home much of the urban realm is dedicated to private car storage. Writing at StrongTowns, Daniel Herriges lays out the key findings from an Urban Three analysis of land use patterns in Kansas City. This map tells much of the story—everything in red is dedicated for parking; all the arrows point to parking structures.

Between parking and the roadway itself (with much of that right-of-way dedicated to parking as well), moving and storing cars is the city’s dominant land use. On a per capita basis the city devotes more land to parking than it does to buildings. How did Kansas City end up with so much parking, you ask? For the answer, you’ll want to read all five installments of Herriges’ series on Kansas City, which chronicles how abandoning streetcars and embracing freeways (and sprawl) led to today’s fiscally challenged “Asphalt City.”

New Knowledge

A carbon price tied to net zero emissions. Economists, ourselves included, love the idea of a pricing carbon. The reason we pollute so much is because everyone gets to treat the atmosphere as a free dumping ground for greenhouse gases. If we charged polluters for the damage their emissions do to the atmosphere, they’d switch to other less polluting or non-polluting activities. The trick is setting the right price for carbon emissions.

In a perfect theoretical world there’s an ideal price for carbon that equilibrates the amount charged to the exact value of a eliminating one more pound of carbon. But in reality, its devilishly hard to compute that price, inasmuch as it depends on complex (and largely insoluble) questions of long term interest rates, technology trends, and questions of inter-generational equity. Consequently, estimates of a fair and equitable “social cost of carbon” are all over the map.

Economists Noah Kaufman and his colleagues propose to cut through this Gordian knot of complexity and disagreement by working backwards from a desired level of carbon emissions, and estimating what price of carbon would be required to reach a specific goal; in their proposal net zero carbon emissions by 2050.

This is of course, a bit of a dodge, inasmuch as choosing a particular goal implies that that corresponds to a social optimum (and it implies values for all those hard to estimate factors that underly a social cost of carbon). But it is a way to truncate the debate and move quickly to action. Their modeling hinges on the accuracy of their technological forecasts and their estimates of the responsiveness of consumer demand, investment and innovation to particular carbon prices. But if they’re right, the solution to climate change would be within reach with 2030 carbon prices of $77 to $120 per ton.

Also, they’re not pricing deists: Prices can be accompanied by selected regulations and investments: Banning coal or fracking and paying compensation for affected workers and communities, and investing in low-carbon research and development would make sense. Pricing helps reinforce these policies.

Kaufman, N., Barron, A.R., Krawczyk, W. et al. A near-term to net zero alternative to the social cost of carbon for setting carbon prices. Nat. Clim. Chang. (2020). https://doi.org/10.1038/s41558-020-0880-3

In the News

City Observatory’s Joe Cortright is quoted extensively in Aaron Gordon’s Vice article on the biases in traffic forecasting models (see “Must Read,” above).

Planetizen offered a detailed summary of our ranking of the nation’s least and most segregated cities.