For most of the 20th century, cities and their accoutrements were associated with immigrants, people of color, and relative economic deprivation. The very phrase “inner city” became a synonym of “poor,” and in certain contexts “urban” itself became a word that referred to people of color, especially black people.

The “great inversion” has challenged that narrative in recent years, as increasing numbers of disproportionately white, upwardly mobile college graduates have moved to downtowns and inner cities around the country. In fact, in analyzing recent Census data, Jed Kolko found evidence that white college graduates were among the only demographics becoming more urban in their living arrangements.

This is all very valuable research—and captures a real phenomenon that has both promise and peril for American cities and suburbs. But there’s a danger in overcorrecting here. (For example, Matt Yglesias’ headline at Vox—“America’s urban renaissance is only for the rich”—sort of skirts that line.) Specifically, while the direction of change is that cities are becoming relatively wealthier and whiter, the actual levels of these populations mean that in most cities, residents are still disproportionately lower-income, foreign-born, and black or brown.

The danger in overcorrecting the conventional wisdom is that we discount the ways in which cities offer important lifelines to people with fewer resources or who are historically disadvantaged. A good example is public transit, and the vastly lower transportation costs that people who live in places with viable transit systems (and the ability to walk or bike for many trips) can enjoy, freeing up household budgets for other necessities. If we imagine that the typical transit rider is a white creative class worker in Brooklyn or the North Side of Chicago, we might discount that redistributive, progressive effect of transit service, and decline to pursue it as a policy goal.

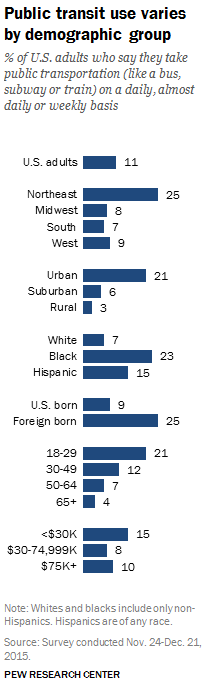

But a recent Pew survey hits home just how far we have to go before the prototypically urban experience of riding the bus or subway becomes a disproportionately white, upper-income phenomenon. Pew asked respondents how often they used public transportation, and published the results with various demographic breakdowns.

The results clearly show that public transit use in America remains disproportionately not the province of whites or upper-income people. Just seven percent of whites—compared to 23 percent of black people and 15 percent of Hispanics—reported using transit at least once a week. A quarter of immigrants took public transit weekly, as opposed to just nine percent of native-born Americans. And those with incomes under $30,000 a year were by far the most likely to be regular riders (15 percent), compared with those making between $30,000 and $75,000 (eight percent) or more (10 percent).

While change makes headlines, actual levels matter too. Cities are, in fact, becoming wealthier and whiter; suburbs are becoming more economically and ethnically diverse. But at least so far, the effect has been to diversify both, rather than lead to a total demographic flip. Cities and “urban lifestyles,” including the use of public transit, are very far from actually being disproportionately wealthy and white, despite the impression you might get in parts of New York or San Francisco.