Increasing road capacity to reduce greenhouse gas emissions will backfire

Widening roads to reduce idling simply induces more travel and more pollution

Cities with faster travel have higher greenhouse gas emissions

Time for another episode of City Observatory’s Urban Myth Busters, which itself is an homage to the venerable Discovery Channel series “Mythbusters” that featured co-hosts Adam Savage and Jamie Hyneman using something called “science” to test whether commonly believed tropes were really true. In each episode, they would construct elaborate (often explosive) experiments to test whether something you see on television or in the movies could actually happen in real life. (Sadly, you can’t make a bullet curve no matter how fast you flick your arm.)

In our first installment, we took on the oft-repeated claim that somehow building more housing for middle and upper income people made housing less affordable for lower income households. (It doesn’t).

Today’s claim comes from the world of transportation. As we all know, transportation is now the single largest source of greenhouse gas emissions. Here, when confronted with the need to do something to address climate change, the highway lobby likes to point out that cars emit carbon, and when they’re idling or driving in stop and go traffic, they may emit more carbon per mile than when they travel at a nice steady speed. And of course, they have a solution for that: spend more money expanding capacity so cars don’t have to slow down so much. That’ll be great for the environment, or so the argument goes.

This claim has been invoked by highway advocates everywhere. Most recently, its been raised by officials speaking in favor of spending upwards of a billion dollars on three freeway widening projects in the Portland area. State Senator Lee Beyer argued that truck idling due to congestion was contributing to global warming. Here’s what Beyer told Oregon Public Broadcasting’s Think Out Loud program on April 18, 2017:

To the extent that we have congestion, in Portland for example, or anywhere else, but there particularly, if you look at the amount of exhaust those trucks are spewing into the air during that 52 hours while they sit in traffic, that may have more of a negative impact on the environment and more carbon release than we would gain solely through the low carbon fuels piece as its currently structured.

His argument was echoed by City Commissioner Amanda Fritz:

It seems likely the emissions from vehicles crawling in this section are worse than those at normal speed.

When he was appointed Director of the Oregon Department of Transportation in 2019, Kris Strickler trotted out the same tired claim:

…. it’s clear about 40% of the greenhouse gas emissions are from the transportation sector, so it’s an important aspect of the work we do. I believe that there is no silver bullet, there is no single answer to address GHG emissions overnight. And its something on our task list and our to-do list as a priority for us as we go forward and we need to attack it in multiple avenues. One is, clearly, through design decisions that we can help to free up and move congested areas, because we know that cars sitting in traffic, frankly, emitting the emissions is not necessarily the best way to manage greenhouse gas reductions.

So is there any truth to the idea that reducing traffic congestion will lower vehicle emissions?

In place of the now retired duo of Adam and Jamie, we’ll turn this question over to Alex and Miguel–Alex Bigazzi and Miguel Figliozzi, two transportation researchers at Portland State University. Their research shows that savings in emissions from idling can be more than offset by increased driving prompted by lower levels of congestion. The underlying problem is our old friend, induced demand: when you reduce congestion, people drive more, and the “more driving” more than cancels out any savings from reduced idling. As they conclude:

Induced or suppressed travel demand . . . are critical considerations when assessing the emissions effects of capacity-based congestion mitigation strategies. Capacity expansions that reduce marginal emissions rates by increasing travel speeds are likely to increase total emissions in the long run through induced demand.

In a companion paper, they look at a variety of data, including variations among metropolitan areas, changes over time in congestion and emissions, and corridor level estimates of traffic and emissions. In each case, they find that carbon emissions are strongly correlated with the length of travel and weakly correlated (or uncorrelated) with levels of congestion.

Specifically, metropolitan areas with high levels of congestion do not have higher levels of CO2 emissions per capita than ones with low congestion. They conclude there is “no relation.” But vehicle miles traveled is a strong correlate. Here’s a chart showing daily peak period hours of vehicle travel per peak period travel (on the horizontal axis) and CO2 emissions per peak period traveler per day. More driving is correlated with more carbon emissions.

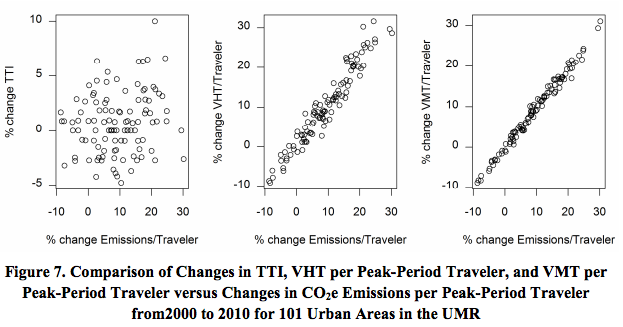

Similarly, metro areas that had an increase in congestion (as measured by the Texas Transportation Institute’s Travel Time Index), didn’t see proportionate increases in CO2 emissions. The following panel shows how the change in emissions per traveler between 2000 and 2010 for an array of 101 metropolitan areas related to changes in congestion (left hand chart), changes in hours traveled per person (center chart) and vehicle miles traveled (right hand chart). There’s essentially no relation between increases in congestion and per traveler emissions; but more hours of travel and greater distances traveled translate very directly into more carbon emissions.

There’s also another kicker to the speed/emissions relationship that you’ll never hear highway advocates mention. While its true that cars emit more carbon per mile while idling and in stop and go traffic than they do when cruising at 30 to 45 miles per hour, traveling at higher speeds is actually less fuel efficient and produces more CO2 per mile driven. Hence one of the strategies that we ought to employ is imposing stricter speed limits (say 55 miles per hour). This also means that the more we build roads that let people drive at higher speeds (60 to 70 miles per hour) the more we’re increasing global warming.

This myth is busted: adding more capacity might reduce idling a bit, but it will actually induce more driving, which will lead to higher, not lower carbon emissions.

And, a technological post-script: Automakers are now increasingly equipping their vehicles with stop-start technology, which automatically turns the engine off when the car stops moving, and then re-starts the engine when the driver takes her foot of the brake. This virtually eliminates idling emissions, not just in traffic, but at red lights too. Some 15 million European cars already have stop-start, a majority of cars sold in North America are predicted to have in the next few years. In addition, electric vehicles don’t idle when they’re stopped. So in the long run, if we want to reduce emissions from idling, a technical fix is in the works–no need to widen roads to address this source of pollution.

This commentary was originally published by City Observatory in 2017. Sadly, six years later, people are still claiming that we can fight climate change by widening roads to reduce the amount of time people spend idling.