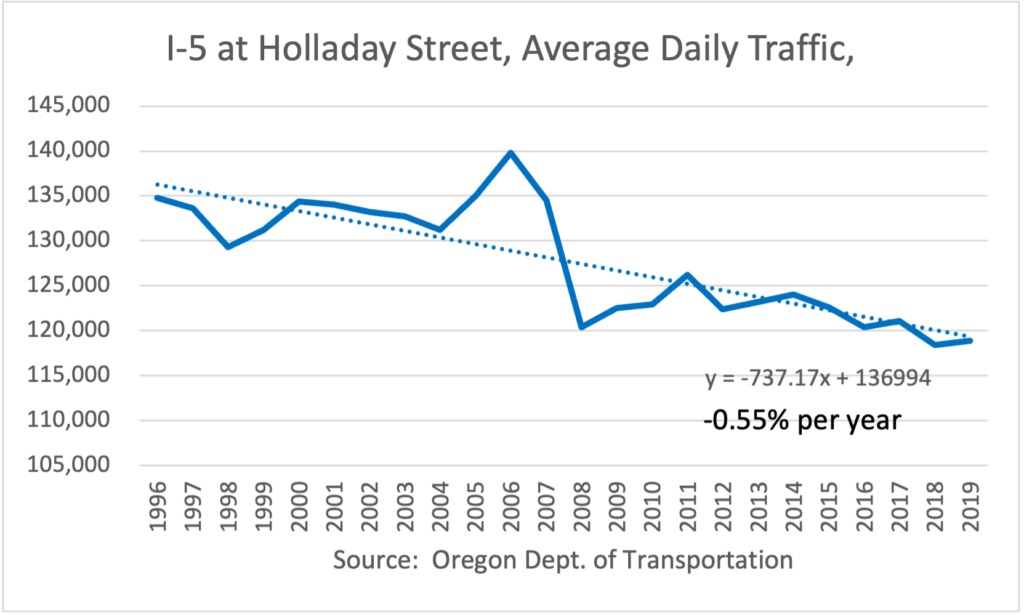

ODOT’s own traffic data shows that daily traffic (ADT) has been declining for 25 years, by -0.55 percent per year

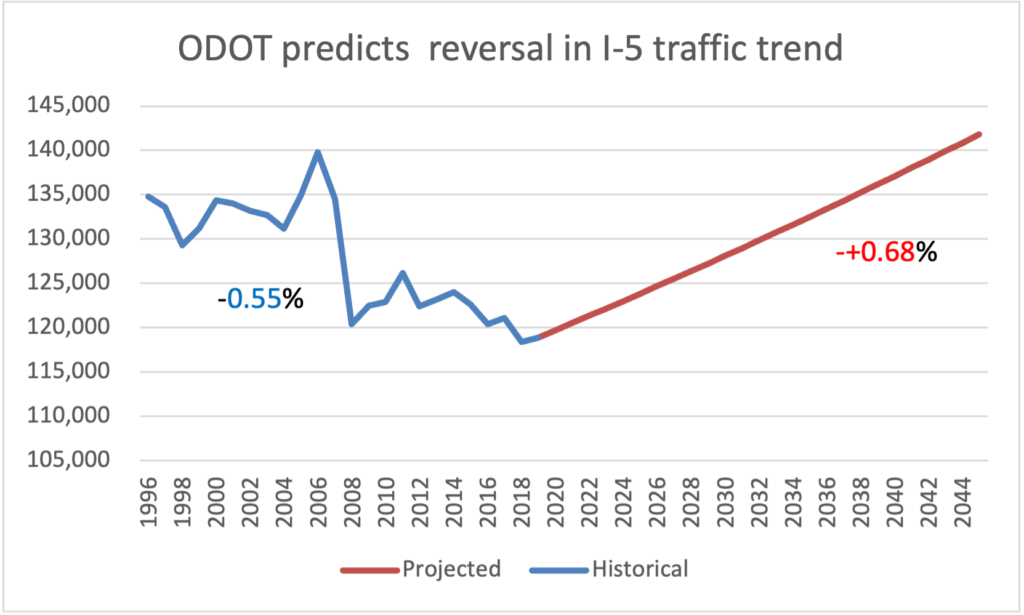

The ODOT modeling inexplicably predicts that traffic will suddenly start growing through 2045, growing by 0.68 percent per year

ODOT’s modeling falsely claims that traffic will be the same regardless of whether the I-5 freeway is expanded, contrary to the established science of induced travel.

These ADT statistics aren’t contained in the project’s traffic reports, but can be calculated from data contained in its safety analysis.

ODOT has violated its own standards for documenting traffic projections, and violated national standards for maintaining integrity of traffic projections.

As we’ve noted, the Oregon Department of Transportation claims it needs to widen the I-5 freeway to meet growing traffic demand. But the agency has been utterly opaque in either presenting its data or describing the methodology it used to reach that conclusion. Neither its draft or supplemental environmental analyses contain any presentation of “average daily traffic” presently or in the future; and ADT is the most basic and widely used measure of traffic. Asked about its methodology, the agency makes vague references to a 40-year old traffic forecasting handbook. This opaque approach to fundamental data both violates NEPA, and the agency’s only standards for professional and ethical practice.

At City Observatory, we’ve found ODOT data—material not included in the project’s Traffic Technical Report—which show that traffic levels on I-5 in the Rose Quarter have been declining for a quarter century, and that the project is assuming that the next twenty five years will suddenly produce a surge in traffic.

Traffic Trends in the Rose Quarter

ODOT maintains a traffic counting program that tracks the number of vehicles traveling on every major roadway in Oregon. We examined the on-line versions of ODOT’s Traffic Volume Tables for the years 1996 through 2019 (i.e. the last full year prior to the Covid-19 pandemic) to establish the historical trend in traffic. We looked at data for the section of I-5 at NE Holladay Street (in the middle of the proposed I-5 Rose Quarter freeway widening project. In 2019, the average daily traffic (ADT) in this section of the Roadway was 118,900 vehicles. That volume of traffic was lower than every year from 1996 through 2017. As the following graph makes clear, the long-term pattern in traffic on this portion of I-5 is downward.

From 1996 through 2019, the average annual change in traffic on this stretch of I-5 was -0.55 percent per year. That downward trend also holds for the last decade: from 2009 through 2019, the average annual change in traffic was -0.30 percent per year. Contrary to the claims of ODOT that this stretch of freeway is seeing more traffic, traffic has actually been decreasing. Nothing in the historic record provides any basis for a claim that traffic on this section of freeway will increase if its capacity is not expanded.

ODOT’s Hidden ADT forecast

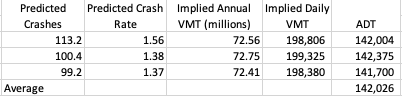

As we’ve noted multiple times at City Observatory, the traffic reports contained in ODOT’s Environmental Assessment (EA) and Supplemental Environmental Assessment (SEA) do not contain any references to Average Daily Traffic. The project’s safety report, however, does contain an indirect reference to average daily traffic. This report uses a safety handbook to compute the number of crashes that are likely to occur on this section of freeway. The handbook method relies on applying a crash rate of a certain number of crashes per million vehicle miles traveled on a stretch of roadway. While ODOT’s safety report doesn’t reveal the ADT figures used, we can use algebra to compute the ADT. ODOT reports the number of crashes and the crash rate per million miles traveled and also the total number of lane miles of freeway included in the analysis. From these three bits of information, we can work out that the average daily traffic for this section of the I-5 freeway is estimated to be 142,000 in 2045. Here are our calculations:

We estimate the implied annual vehicle miles traveled in millions by dividing the predicted crashes by the predicted crash rate. We then estimate daily vehicle miles traveled by dividing annual VMT by 365. Finally, we computed average daily traffic by dividing VMT by the number of miles in the subject roadway segment (1.4). This produces an estimate of approximately 142,000 ADT for this segment of I-5 in 2045.

This future traffic level forecast implies that traffic will increase by about 22,000 vehicles per day between 2019 and 2045. This works out to an annual growth rate of 0.68 percent. In essence, ODOT is predicting that even though traffic has declined by 0.55 percent per year for the past quarter century, it will over the next quarter century grow by 0.68 percent per year. How or why this is likely to happen is never explained or documented in the EA or Supplemental EA.

Also, as we’ve noted before, ODOT’s traffic forecast for the I-5 Rose Quarter, according to its safety analysis, is for the same level of traffic in 2045 in both the Build and the No-Build scenario. This claim flies in the face of what we know about the science of induced travel: the construction of additional lanes creates added capacity, which will induce more trips in the corridor—if the project is built, but not if it isn’t. The prediction of higher traffic levels for a build scenario may be plausible, but for a no-build scenario it is unlikely that there would be any traffic growth, especially given the established 25-year trend of declining traffic on this portion of I-5. By over-estimating travel in the No-Build scenario, the EA conceals the increased driving, pollution and likely crashes from widening the freeway.

In theory, the National Environmental Policy Act is all about disclosing facts. But in practice, that isn’t always how it works out. The structure and content of the environmental review is in the hands of the agency proposing the project, in this case the proposed $1.45 billion widening of the I-5 Rose Quarter freeway in Portland. The Oregon Department of Transportation and the Federal Highway Administration have already decided what they want to do: Now they’re writing a set of environmental documents that are designed to put it in the best possible light. And in doing so, they’re keeping the public in the dark about the most basic facts about the project. In the case of the I-5 project, they haven’t told us how many vehicles are going to use the new wider freeway they’re going to build.

No New Regional Modeling

The Traffic Technical Report of the Supplemental Environmental Assessment makes it clear that ODOT has done nothing to update the earlier regional scale traffic modeling it did for the 2019 Environmental Assessment. ODOT claims it used Metro’s Regional Travel Demand Model to generate its traffic forecasts for the i-5 freeway—but it has never published that models assumptions or results. And in the three years since the original report was published, it has done nothing to revisit that modeling. The traffic technical report says:

. . . the travel demand models used in the development of future traffic volumes incorporated into the 2019 Traffic Analysis Technical Report are still valid to be used for this analysis.

What ODOT has never done is “show its work”—i.e. demonstrate how its estimates and modeling turned a highway that was seeing declines of 0.55 percent per year for a quarter century into one where we should expect 0.68 percent increases in traffic ever year for the next quarter century. In its comments on the 2019 EA, a group of technical experts pointed out a series of problems with that modeling. Because ODOT made no effort to update or correct its regional modeling, all of those same problems pervade the modeling in the new traffic technical report.

Hiding results

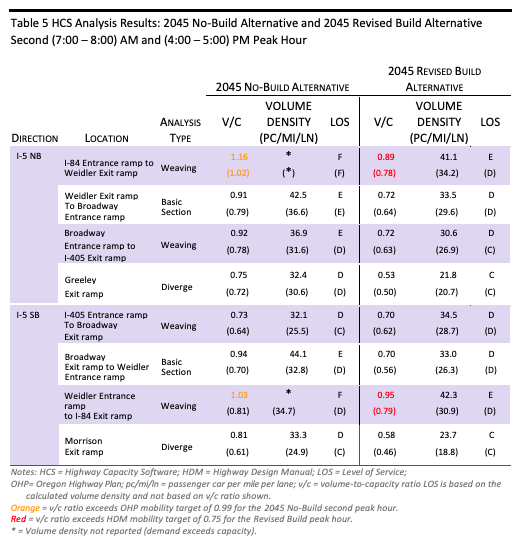

ODOT has gone to great lengths to conceal its actual estimates of future average daily traffic on I-5. Neither the 2019 Environmental Assessment, nor the 2022 Supplemental Environmental Assessment’s traffic reports contain any mention of average daily traffic. As illustrated above, ODOT also expunged the actual ADT statistics from the safety report as well (even though its calculations make it clear that it is assuming that this stretch of freeway will have 142,000 ADT. And when you look at what is presented, ODOT has purposefully excluded any indication of actual traffic levels. The supplemental traffic analysis presents its results in a way that appears designed to obscure, rather than reveal facts. Here is a principal table comparing the No-Build and Build designs.

Notice that the tables do not report actual traffic volumes, either daily (ADT) or hourly volumes. Instead, the table reports the “V/C” (volume to capacity) ratio. But because it reveals neither the volume, nor the capacity, readers are left completely in the dark as to how many vehicles travel through the area in the two scenarios. This is important because the widening of the freeway increases roadway capacity, but because ODOT reveals neither the volume nor the capacity, it’s impossible for an outside observer to discern how many more vehicles the project anticipates moving through the area. This, in turn, is essential to understanding the project’s traffic and environmental impacts. It seems likely that the model commits the common error of forecasting traffic volumes in excess of capacity (i.e. between I-84 and Weidler) in the No-Build. As documented by modeling expert Norm Marshall, predicted volumes in excess of capacity are symptomatic of modeling error.

ODOT is violating its own standards and professional standards by failing to document these basic facts

The material provided in the traffic technical report is so cryptic, truncated and incomplete that it is impossible to observe key outputs or determine how they were produced. This is not merely sloppy work. This is a clear violation of professional practice in modeling. ODOT’s own Analysis Procedures Manual (which spells out how ODOT will analyze traffic data to plan for highway projects like the Rose Quarter, states that the details need to be fully displayed:

6.2.3 DocumentationIt is critical that after every step in the DHV [design hour volume] process that all of the assumptions and factors are carefully documented, preferably on the graphical figures themselves. While the existing year volume development is relatively similar across types of studies, the future year volume development can go in a number of different directions with varying amounts of documentation needed. Growth factors, trip generation, land use changes are some of the items that need to be documented. If all is documented then anyone can easily review the work or pick up on it quickly without questioning what the assumptions were. The documentation figures will eventually end up in the final report or in the technical appendix.The volume documentation should include:• Figures/spreadsheets showing starting volumes (30 HV)• Figures/spreadsheets showing growth factors, cumulative analysis factors, or travel demand model post-processing.• Figures/spreadsheets showing unbalanced DHV• Figure(s) showing balanced future year DHV. See Exhibit 6-1• Notes on how future volumes were developed:o If historic trends were used, cite the source.o If the cumulative method was used, include a land use map, information that documents trip generation, distribution, assignment, in-process trips, and through movement (or background) growth.o If a travel demand model was used, post-processing methods should be specified, model scenario assumptions described, and the base and future year model runs should be attached

This is also essential to personal integrity in forecasting. The American Association of State Highway and Transportation Officials publishes a manual to guide its member agencies (including ODOT) in the preparation of highway forecasts. It has specific direction on personal integrity in forecasting. National Cooperative Highway Research Project Report, “Analytical Travel Forecasting Approaches for Project-Level Planning and Design,” NCHRP Report #765—which ODOT claims provides its methodology— states:

It is critical that the analyst maintain personal integrity. Integrity can be maintained by working closely with management and colleagues to provide a truthful forecast, including a frank discussion of the forecast’s limitations. Providing transparency in methods, computations, and results is essential. . . . The analyst should document the key assumptions that underlie a forecast and conduct validation tests, sensitivity tests, and scenario tests—making sure that the results of those tests are available to anyone who wants to know more about potential errors in the forecasts.

Appendix: Expert Panel Critique of Rose Quarter Modeling

[pdf-embedder url=”https://cityobservatory.org/wp-content/uploads/2022/11/RQ-Model-Critique.pdf” title=”RQ Model Critique”]

Updated December 2, 2023