What City Observatory did this week

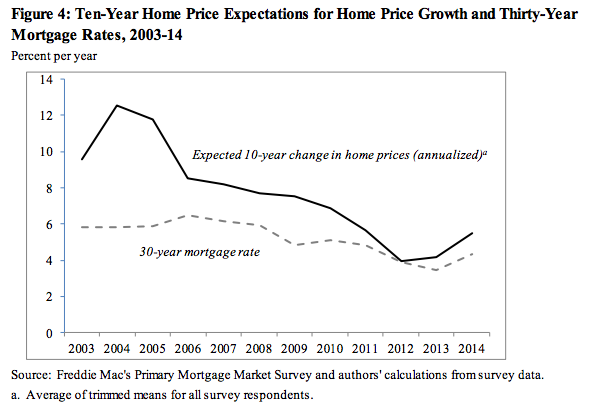

1. Bubble Logic. A major and persistent change in the housing market from a decade ago has been the decline in the number of “trade-up” home-buyers. While some fret that recent first-time homebuyers have become locked in to so-called starter homes, we point out that in many ways, trade-up demand was a product of the unsustainable housing bubble of the last decade. The lingering effects of the bubble’s collapse, and an enduring change in expectations about home price inflation strongly suggest we won’t see a resurgence of trade-up demand anytime soon.

2. Why a housing lottery won’t solve our affordability problems. Inclusionary zoning programs require developers to set aside some units in new developments for low and moderate income households. Because tens of thousands of households are potentially eligible for a few hundred units, cities face the practical problem of choosing who gets to buy or rent these cut-price homes. Sally French tells the story of how she entered, and won, San Francisco’s housing lottery, and was able to buy a new condo for about one-third the going rate. That’s great for her—and a relative handful of others—but is hardly a scalable solution to our housing affordability problems. Her experience shows that you also need a good deal of savvy and persistence to negotiate the lottery process.

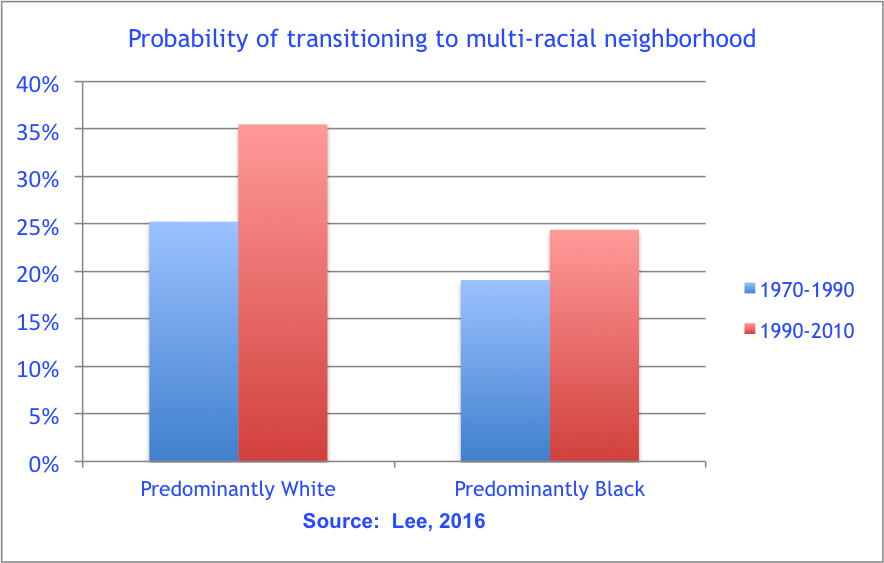

3. Are integrated neighborhoods stable? Its long been popular to think of the process of neighborhood change as being characterized by “tipping points.” Once the demographics of a neighborhood start changing, from say mostly white, to more mixed race, it tends to “tip” to being entirely a community of color, because many whites may not feel comfortable if they’re not a majority. New evidence of neighborhood change shows that once established, mixed race neighborhoods are in fact stable.

4. A memo for Stockholm. Next Monday, we’ll learn the name of the latest Nobel laureate in economics. We think a good case could be made that the award should go to Paul Romer, recently named as the new chief economist for the World Bank. Romer’s seminal contributions to New Growth Theory have long been recognized by his academic peers—and have important implications for urban economic policies. And in recent days, Romer has been making a strong case that the profession’s approach to macroeconomic policy has become profoundly unscientific and needs to be fundamentally re-thought. This is the kind of thoughtful and provocative speaking truth to power that the Nobel prize ought to recognize.

This week’s must reads

1. How we talk about pedestrian deaths. More than 4,000 pedestrians are killed in car crashes each year, and the way their deaths are reported in the media obscures the systemic nature of this problem. In an essay at Streetsblog, Angie Schmidt points out that press stories routinely call deaths “accidents,” tend to blame the victims, describe the car, rather than its driver as the cause of the crash, and fail treat design of streets as a factor in the deaths. We know that multi-lane arterials and streets that encourage high travel speeds are responsible for a disproportionate share of pedestrian deaths.

2. Thinking hard about infrastructure investment. The two major party Presidential candidates may agree in some general way about infrastructure, but urban economist Ed Glaeser does not. In an Interview with Vox, Glaeser points out we need to re-think the way we invest in infrastructure. Current approaches tend to systematically neglect maintenance in favor of shiny new projects, infrastructure investments are seldom subjected to serious cost-benefit analysis, and actual users rarely pay for the costs of projects they benefit from—which in some cases amplifies inequality. And in the case of roads, building more capacity without implementing some form of road pricing simply stimulates more demand—the fundamental law of road congestion.

3. Making mixed use developments legal. President Obama got a lot of press in the urbanist world last week with the release of the White House’s housing toolkit—essentially a list of recommended policy changes that states and cities could undertake to allow more density. Writing this week in the Washington Post, Jonathan Coppage points out that the federal government could play a key role here as well, by changing its guidelines on residential mortgages to make it easier to include commercial space in residential buildings – think ground floor shops with apartments above. Currently, federally purchased or guaranteed loans can only go to projects with no more than 15 to 25 percent non-residential uses, effectively precluding this important form of financing for developments that are less than four stories in height.

New knowledge

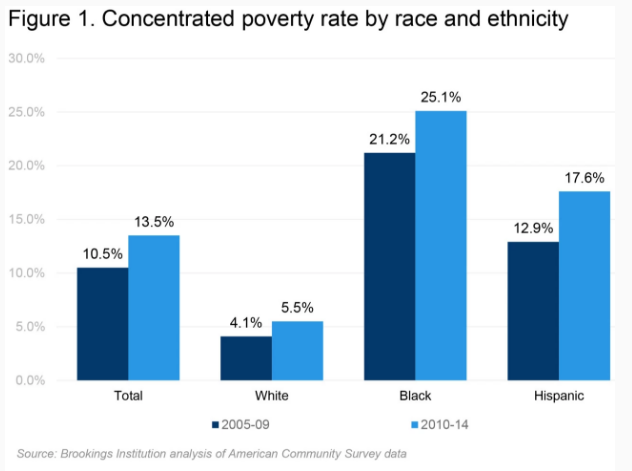

1. Concentrated Poverty in the Wake of the Great Recession. The Brookings Institution’s Elizabeth Kneebone and Natalie Holmes have sifted through the 2010-2014 five-year American Community Survey to track the growth of concentrated poverty in the US. Concentrated poverty is defined in their work as neighborhoods with a poverty rate of 40 percent or higher. Their key finding: since 2009, the number of people living in these extremely poor neighborhoods has increased 34 percent, from 8.7 million to 13.7 million. That comes on top of a big increase in concentrated poverty since 2000; the number of people living in these high poverty neighborhoods in the US has more than doubled since 2000. Concentrated poverty disproportionately affects people of color: blacks are nearly five times likelier than whites to live in neighborhoods of concentrated poverty. And despite the much noted increase in the number of people living in poverty in the suburbs, concentrated poverty is much more common in cities: about one in four poor persons in cities lives in a neighborhood of concentrated poverty, compared to about 1 in fourteen poor persons living in the suburbs. The Brookings report has detailed data on the top 100 metropolitan areas.

2. US consumers pay some of the highest real estate commissions in the world. A new survey of real estate broker commissions in 17 countries around the world shows that the US pays an average commission of about 5.5 percent, compared with about 1.5 to 3.0 percent in other high income countries. While commissions in the US have declined slightly from an average of about 6.0 percent in 2002, the declines in other nations have on average been much sharper. Commissions in Canada have fallen from about 4.5 percent a decade ago, to about 3.0 percent per day. Lower real estate commissions would make houses more affordable for everyone and lower transaction costs for real estate sales would make it easier for households to move to new homes and new neighborhoods.