What City Observatory did this week

1. How green was my city? The Trump administration’s announcement that it would pull the US out of the Paris Climate Accords was greeted with dismay by many environmentalists, but governors and mayors around the nation stepped up to say they’d continue to fight climate change. Climate hawks are no doubt buoyed by the support, but state and local governments need to back up the rhetoric with strong action. Chief among these: foreswearing more spending on expanding road capacity. Its impossible to reconcile a commitment to reducing greenhouse gases with measures that essentially subsidize more driving.

2. Portland’s green dividend. We reprise our 2007 report looking at the economic benefits that a local economy reaps when it is built in a way that its residents don’t have to drive as much or as far. Portland residents drive about 20 percent fewer miles than the average urban resident, saving them more than $1 billion a year in out of pocket costs for cars and gasoline. That money then gets spent in the local economy.

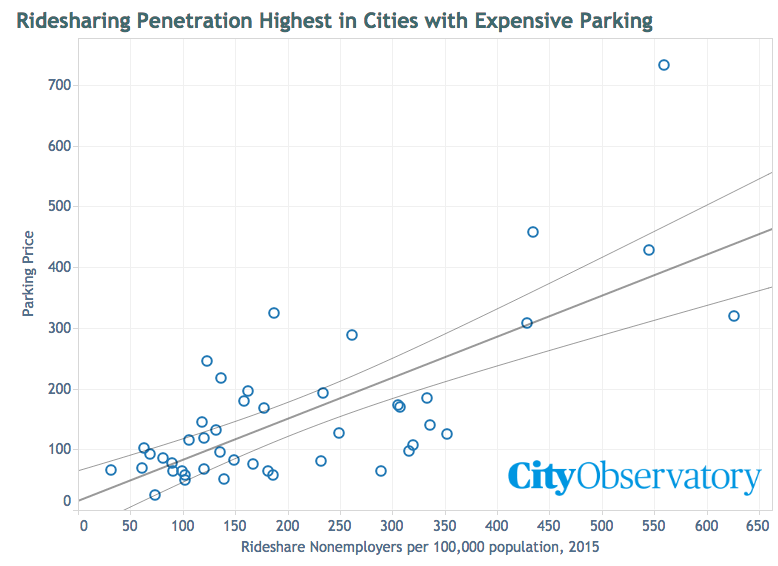

3. More evidence on the growth of ride-hailing services. The Brookings Institution has worked out a clever way to estimate the size and growth rate of the ride-hailing businesses using tax filings by the independent driver/owners who contract with Uber, Lyft and others. Their analysis shows the industry grew by almost xx percent in 2015 over the previous year, and involved more than 500,000 contractors nationally. We map out the relative size of the ride-hailing business in each of the nation’s large metro areas, and show how its strongly correlated to local parking prices. Ride hailing is the biggest where parking is most expensive, more evidence that how we price transportation affects how it works.

Must read

1. Roots of segregation run deep. In his new book, The Color of Law Richard Rothstein takes a retrospective look at the causes of persistent racial segregation in the US. He points out that federal policies dating from the 1930s and 1940s contained explicit racial provisions–for example, banning the sale of homes or the provision of mortgages to blacks in white neighborhoods. Those provisions, coupled with other policies became entrenched, and had profound long-term effects in limiting the opportunity of Black Americans to invest in housing in the neighborhoods that enjoyed the greatest appreciation. The segregation we see today is in many respects a measure of how deep and enduring the effects of those policies have been.

2. There’s something wrong with Connecticut. For decades, it seems, suburban Connecticut has been the destination of choice for big name companies looking to move out of New York City to a leafy, and low tax campus environment. But the growing movement of companies back to city centers is having a dramatic impact on places like Connecticut. Hartford based insurance giant Aetna has just announced it will follow in the footsteps of GE and move its headquarters out of the state, chiefly to get better access to talented workers. Slate’s Henry Grabar notes that while the state continues to have lower business taxes than its competitors, it isn’t competitive in offering a sense of place: “The deeper, more daunting question is what besides a tax break will make Connecticut a place people want to live and work. The state still hasn’t found the answer.”

3. Parking requirements penalize the poor. Its commonplace for local zoning codes to require that developers build new, off-street parking in order to receive planning permission for new homes or apartments. Parking can easily add $20,000 or more to the cost of a new apartment, and that price ultimately is passed on to renters whether or not they actually own cars. A new study from UCLA estimates that low income households that don’t own cars pay $440 million annually in higher rents to cover the costs of parking spaces that they don’t use.

4. The theory and practice of re-thinking parking. CNU’s Public Square has an interview which combines the research insights of parking guru Don Shoup with the practical experience of planning consultant Jeffrey Tumlin of Nelson/Nygaard. They describe, in simple terms, why cities have a strong interest in reducing parking requirements and pricing street parking correctly, and outline the steps cities can take to turn parking from a problem into an opportunity to revitalize urban spaces. Separating land uses, limiting density and requiring the provision of free parking has predictably generated an auto-dependent urban form. Fixing parking is a critical step in un-doing that pattern.

New ideas

Concentrated poverty and neighborhood change in the Netherlands. Like the US, cities in the Netherlands have been demolishing some large scale low income housing complexes and working to rebuilding these neighborhoods are more mixed income places. A new study from the Delft University looks at the effects of this effort. The redevelopment process has resulted in higher incomes in redeveloped neighborhoods, and hasn’t produced a re-concentration of poverty elsewhere. As the authors explain: “large-scale demolition does not seem to lead to new concentrations of low income households in other deprived neighborhoods As such, large-scale demolition seems to be effective in breaking up concentrations of poverty by creating a larger geographical spread of low-income households.”