What City Observatory did this week

1. Why median rents are an incomplete and often misleading indicator of housing affordability. Our colleague Daniel Hertz shows how the median rent statistics that are often cited to demonstrate whether a neighborhood or city has a housing affordability problem can be a misleading guide. Medians tell us little about the rents or prices in the lower tail on the housing cost distribution, and some neighborhoods have a wide mix of housing types (and prices) while others are much more clustered around the median. Hertz shows that using the lower quartile rent or home value (available from the Census Bureau’s American Community Survey) can provide a richer picture of housing affordability for lower income households.

2. Higher inequality neighborhoods reduce inequality. Here’s a paradox: while wide income inequality at the national level is a sign of growing separation, a high level of inequality in incomes at the neighborhood level actually signifies a place with a high level of economic integration. When a neighborhood has a wide range of housing types (from smaller, affordable and often publicly-subsidized apartments, to larger more luxurious housing) it means that people from a range of different income groups can live near one another, which has the effect of reducing economic segregation.

Must read

1. What’s wrong with Connecticut? Writing at the Atlantic Derek Thompson looks into the woes of Connecticut. The state’s income numbers have long been impressively buoyed by the affluent suburbs bordering New York, but in the past few years that suburban advantage has faded. Two corporate stalwarts (GE and more recently Aetna) have relocated their headquarters outside the state, leading many to question its economic future. And Connecticut faces stiff competition from the newly vibrant city-centered economies in Boston and New York City.

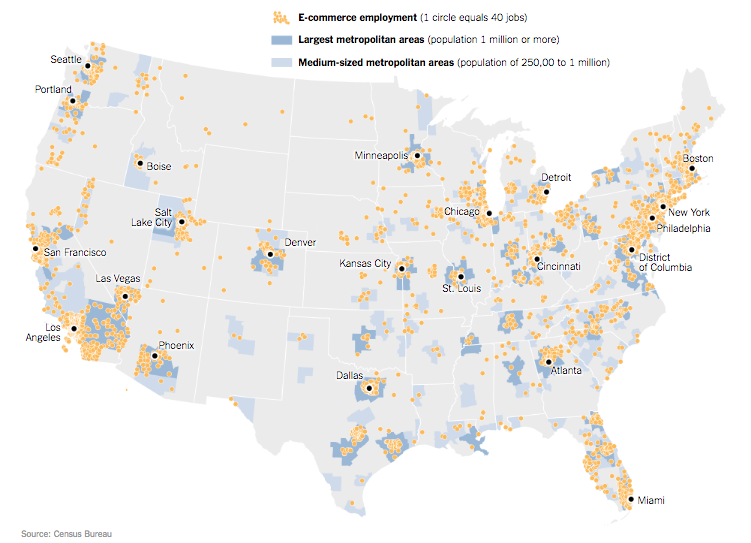

2. Where retail is declining and e-commerce is growing. The New York Times has a nice data visualization showing the decline of employment in retailing (especially in department stores) and the concomitant growth of jobs in e-commerce. Interestingly, there’s a decided pro-urban shift here. Rural areas account for 23 percent of jobs in retailing (where losses are concentrated) but only 13 percent of jobs in e-commerce (where gains are being recorded. It’s further evidence of how technological and economic change is advantaging urban economies.

3. Another installment in the YIMBYs vs. Socialists Battle. The California Planning and Development Report relates the latest chapter in the battle between anti-gentrification socialists in San Francisco, and the YIMBY movement (personified by the Bay Area Renter’s Federation), which takes an aggressively pro-development stance as a strategy for tackling housing affordability. The heresy of the YIMBY activists, from the socialist point of view, is that they’ve made common cause with the exploiters (development community) and therefore must be somehow undermining the interests of the downtrodden. All this is served up with heaping helpings of invective. CP&DR’s Josh Stephens tries to spell out the common ground between the two camps, but both the rhetoric and personal animosity have already become quite heated. Look for all this to come to a head in the next few weeks when the national YIMBY annual conclave touches down in Oakland.

New ideas

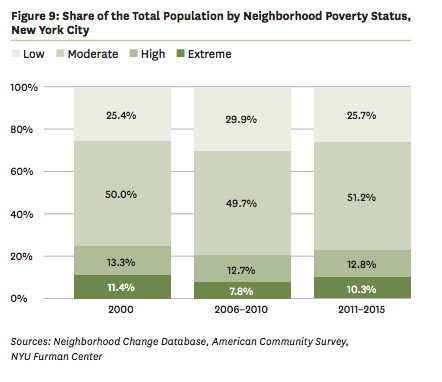

An increase in concentrated poverty in New York City. While gentrification tends to generate headlines, the steady expansion of concentrated poverty is a far larger and more pernicious problem. The Furman Center at New York University has just released its analysis of data from the American Community Survey plotting the increase in concentrated poverty–neighborhoods where more than 30 percent of residents live in households with incomes below the federal poverty line. One in five New York City neighborhoods have poverty rates in excess of 30 percent; more than half of the neighborhoods in the Bronx are high poverty by this standard. The share of New York City’s population living in high (or extreme) poverty neighborhoods increased from 20.5 percent in 2006-10 to 23.1 percent in 2011-15 (after falling in the period since Census 2000. About 45 percent of all New Yorker’s living in poverty live in neighborhoods where the local poverty rate exceeds 30 percent.