What City Observatory did this week

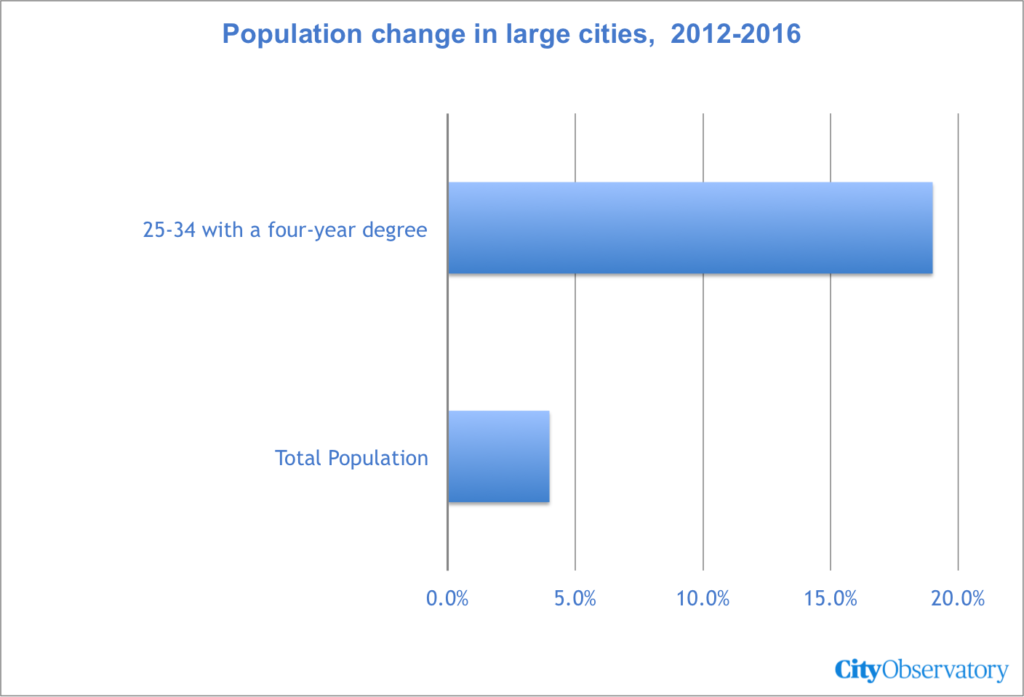

1. Cities continue to attract the young and restless. We’ve seen some push-back in the last few months, arguing that city population growth is no longer outpacing suburbs, and that the movement back to cities is threatened by “peak-millennials.” That led us to take a close look at the latest data on city population growth, with a focus on the number of 25 to 34 year olds with a college degree, a demographic we call “the young and restless,” in part because they’re the most mobile Americans. These smart young workers are still moving to cities in large numbers: between 2012 and 2016, the number of 25 to 34 year olds with at least a four-year degree living in the largest 50 cities in the US increased by about 19 percent, nearly five times faster than the 4 percent total increase in population in these cities. All but two of the 50 largest cities saw increases in this demographic, which is even more concentrated in large cities than it was four years ago.

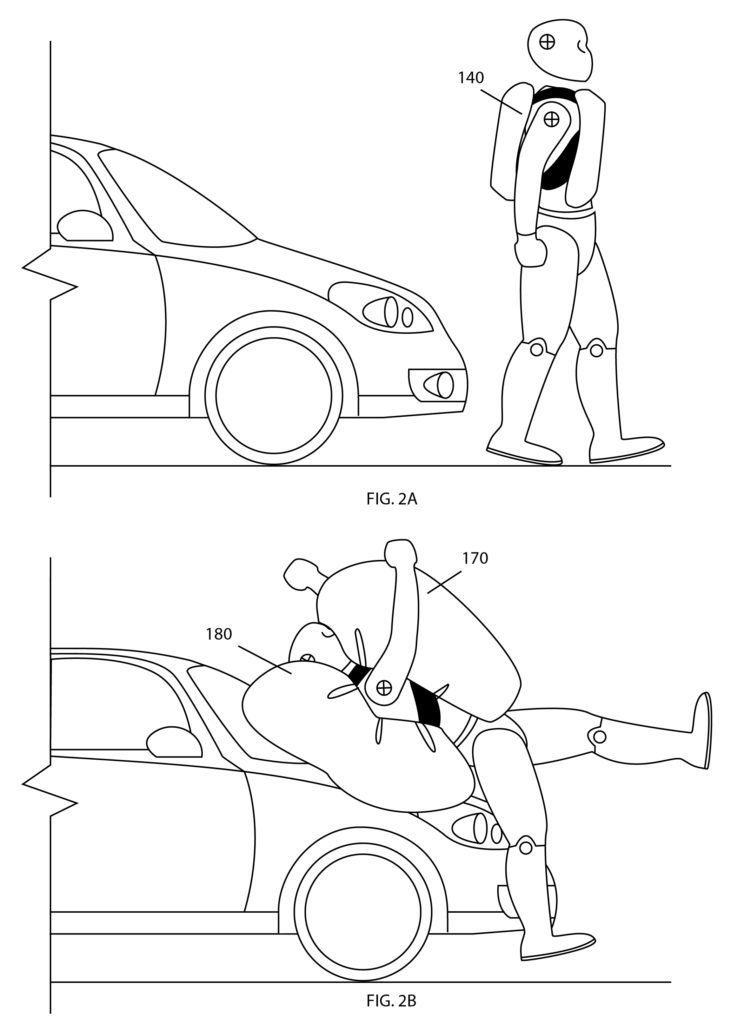

2. There isn’t a technological fix for pedestrian safety. If you are an automotive engineer, it seems, we’re always just one more technological fix away from safer travel. The latest evidence of that phenomenon is GM’s patent for external air bags on cars to cushion pedestrians when cars crash into them. It reminded us of Google’s patent from a couple of years back to create flypaper like automobile hoods that would catch pedestrians. (We’ll leave it to others to decide whether its better for a pedestrian to stick to a car or be bounced off by an air-bag). The point is that while these are billed as “pedestrian safety” measures, they’re really about making the roadway more amenable to car traffic. And that attitude is really the biggest threat to pedestrian safety.

Must read

1. Krugman: The gambler’s ruin of small cities. Paul Krugman takes a short break from his regular commentary on the current national political economy to indulge his longer term academic interest in the geography of economic growth. What’s to become of the nation’s smaller cities, he asks. Arguably, much of the basis for urbanization around the country is two-fold: the need to provide central service centers (education, health care, banks, stores) for the more dispersed agricultural population, and the clustering of relatively smaller scale manufacturing industries. Many of these clusters emerge gradually and serendipitously over time, but it appears that especially in the case of manufacturing industries, fewer such clusters are developing. Small cities may essentially be “one-hit-wonders” with economic success tied to the flourishing of a particular industry at a particular time; the chances that smaller cities will find a second act is an increasingly unlikely proposition, what Krugman characterizes as the gambler’s ruin: “In the modern economy, which has cut loose from the land, any particular small city exists only because of historical contingency that sooner or later loses its relevance.”

2. Emily Badger: How globalization draws our richest cities into a different role. Krugman’s musing about the fate of smaller cities was promprompted by this piece from his NYT colleague Emily Badger. Badger notes that major US cities, like New York and San Francisco, now have a fundamentally different economic structure, dictated by the leading roles they play in global technology and finance. A key characteristic of the knowledge based economy is that these successful cities build powerful and self-reinforcing combinations of industrial clusters, talented workers, global connections and serial entrepreneurs that accelerate the divergence between them and the rest of the economy.

3. Zillow: Homeowners racked up almost $2 trillion in capital gains in 2017. The real estate information firm Zillow compiles detailed, nearly real time data on the value of the U.S. housing stock. As of the end of the year, they reckon the value of the nation’s homes and apartments to be about $31.8 trillion. Based on their analysis of sales trends, the total value of housing increased by slightly less than $2 trillion over the last year. That’s a good measure of how much collectively, homeowner’s gained in appreciation over the year. As we’ve suggested before, taxing a portion of that gain might be a way of generating funds to address our affordable housing problems. But for nearly all homeowners, these capital gains are exempt from federal taxation, a policy that’s largely continued under the new tax bill.

New knowledge

Does broadband Internet boost educational performance? One of the articles of faith in the technological community, or so it seems, is that faster Internet connections are just bound to help kids learn more and faster. But do those with access to high speed Internet actually perform better academically? A new study looks at the school performance of more than 250,000 Swedish teenagers, and tests whether those with access to fiber optic Internet service progressed as rapidly through school. They find for boys, the availability of fiber had a small negative effect on Grade Point Average: going from 0 percent fiber service in a neighborhood to 100 percent was associated with a decline in GPA of 4 to 8 percent of a standard deviation. The authors hypothesize that faster Internet speeds may have led students to spend more time on the Internet, but disproportionately for leisure, rather than studying. The effect however, is quite small; but it does tend to discredit the common assumption that faster speeds will promote greater learning. (Erik Grenestam & Martin Nordin, High-Speed Broadband and Academic Achievement in Teenagers: Evidence from Sweden, Lund University, Department of Economics, School of Economics and Management, December 2017).