What City Observatory did this week

1.How urban geometry creates neighborhood identity. Our colleague Daniel Hertz is back this week with an examination of the way we look at and think about neighborhood identities. He points out that in many urban neighborhoods the amount of land taken up by single family homes creates the impression that most families must live in such buildings. But because they are so space efficient and usually concentrated, multi-family homes–though less visually apparent–may actually be home to a larger fraction of all households. This subtle perceptual bias is important because it underscores widely repeated notions of what kinds of development are and aren’t “in keeping with the character of the neighborhood.”

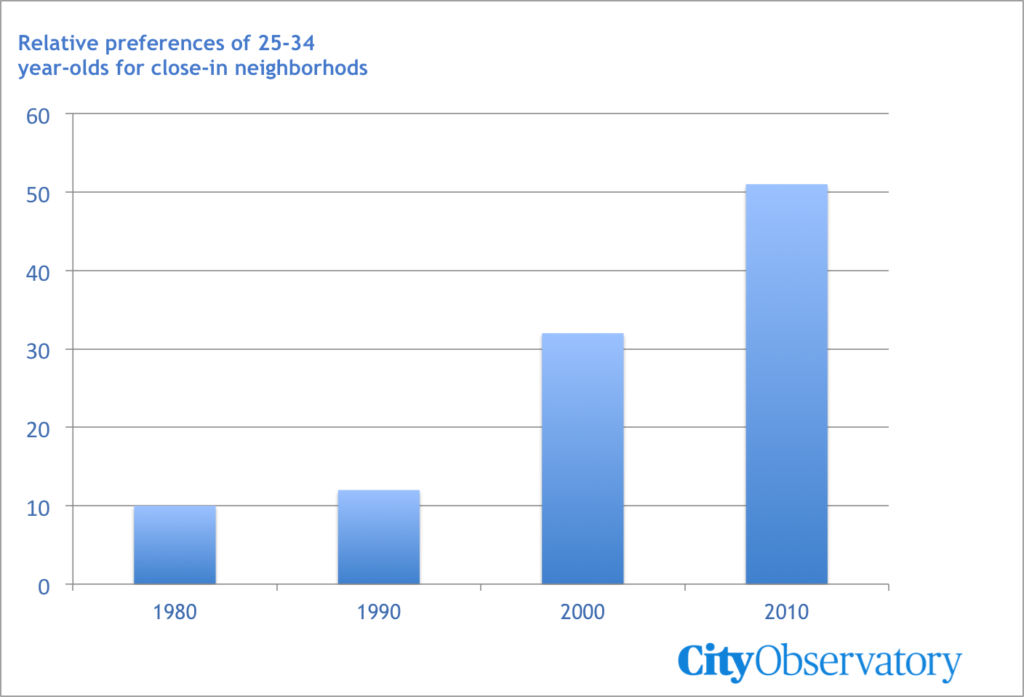

2. Peak millennial? Not yet. Not soon. And not about to undermine urban revival. The New York Times published a contrarian article suggesting that the nation’s recent urban rebound might be undermined by the cresting of a demographic wave. We pushed back at City Observatory, pointing out that the number of 25 to 34 year olds in the nation’s population will continue to increase through 2024 (and plateau but not decline thereafter). More importantly, the growth in the number of young adults in urban centers has been propelled not primarily by the size of this age cohort, but instead by the growing relative affinity of young adults for urban living. Compared to the 1980s and 1990s, 25 to 34 year olds today are much more likely to live in urban neighborhoods–a trend that shows no signs of abating.

3. Suburban renewal. Its been a long time since big cities pursued heavy-handed strategies of urban renewal, demolishing whole neighborhoods–usually of modest income households, and communities of color. In Marietta, Georgia, however, that old tactic got a new lease on life when the city government used local tax revenues to buy up, then demolish hundreds of affordable apartments. In their place, the city leased out the land to Atlanta’s new major league soccer franchise to use as a practice facility. While such a policy would undoubtedly create enormous outcry in a city, it goes almost unremarked upon in the suburbs. Perhaps this reflects a deeply ingrained but seldom-voiced bias in our views about place: Suburbs are for rich, mostly white people. Cities are for poorer people and people of color. Anything change that runs counter to this worldview (like gentrification of a Brooklyn neighborhood, or efforts to build affordable apartments in suburbs like Marin County) is an affront to the order of things.

4. Does gentrification lead to increasing movement out of neighborhoods? It’s often assumed that when a neighborhood gentrifies, we see a large increase in movement out of the neighborhood by existing residents. A new study published in the Urban Affairs Review compares out-migration rates from gentrifying and non-gentrifying neighborhoods. It finds that the overall migration by renters from gentrifying neighborhoods is no higher than in non-gentrifying neighborhoods. The study does detect a small increase in the number of involuntary moves by renters, finding about 2.6 percent more involuntary moves over a two-year period in gentrifying neighborhoods. But to put that number in context, in gentrifying and non-gentrifying neighobrhoods alike, more than half of all renters (54 percent) move out after two years. The study shows that gentrification has no effect on the rate at which homeowners move from neighborhoods.

Must read

1. How to Price Parking. Don Shoup has famously written an entire tome on how and why to price parking. But where to start? Next City has published the tale of one company’s successful effort to apply Shoupian principles to its own parking. The story is told by Evan Goldin, who was a product manager (and parking lot manager) for transportation network company Lyft. When Lyft moved its operations to San Francisco in 2014, it decided to start charging for parking, and used the net revenues to subsidize other employee transportation choices, including transit. It took some tweaking with prices and policies, but the result has been positive for everyone: those who need and value a dedicated parking space are assured of having one, and those who don’t drive have some of their commute costs subsidized by those who drive. While the article is entitled “How I helped to change the commuting culture at Lyft,” it’s clear that the commuting changed in response to a change in prices, not because of a kumbaya transformation of the company or its employees.

2. Infrastructure “Clash of the Titans” at Brookings. Two of the nation’s leading economists–both from Harvard–former Treasury Secretary Larry Summers and Triumph of the City author Ed Glaeser, debated the economic merits of a national infrastructure investment push. Summers stressed the macroeconomic argument in favor: more government spending at a time of historically low interest rates is likely to help stimulate long-term economic growth. Glaeser took a more skeptical position, and stressed the microeconomic view: infrastructure projects ought to be subjected to clear cost-benefit tests, and it makes sense to insist that most projects be financed by user fees that place the costs of building such projects on those who will benefit. Pricing not only pays for projects by provides strong incentives to build only those projects that have an economic return. You can read Brookings synopsis of the event or watch their speeches on-line at the Brooking website. Also worth reading: Matt Kahn’s take on the debate: (he’s the one who came up with “Clash of the Titans.”)

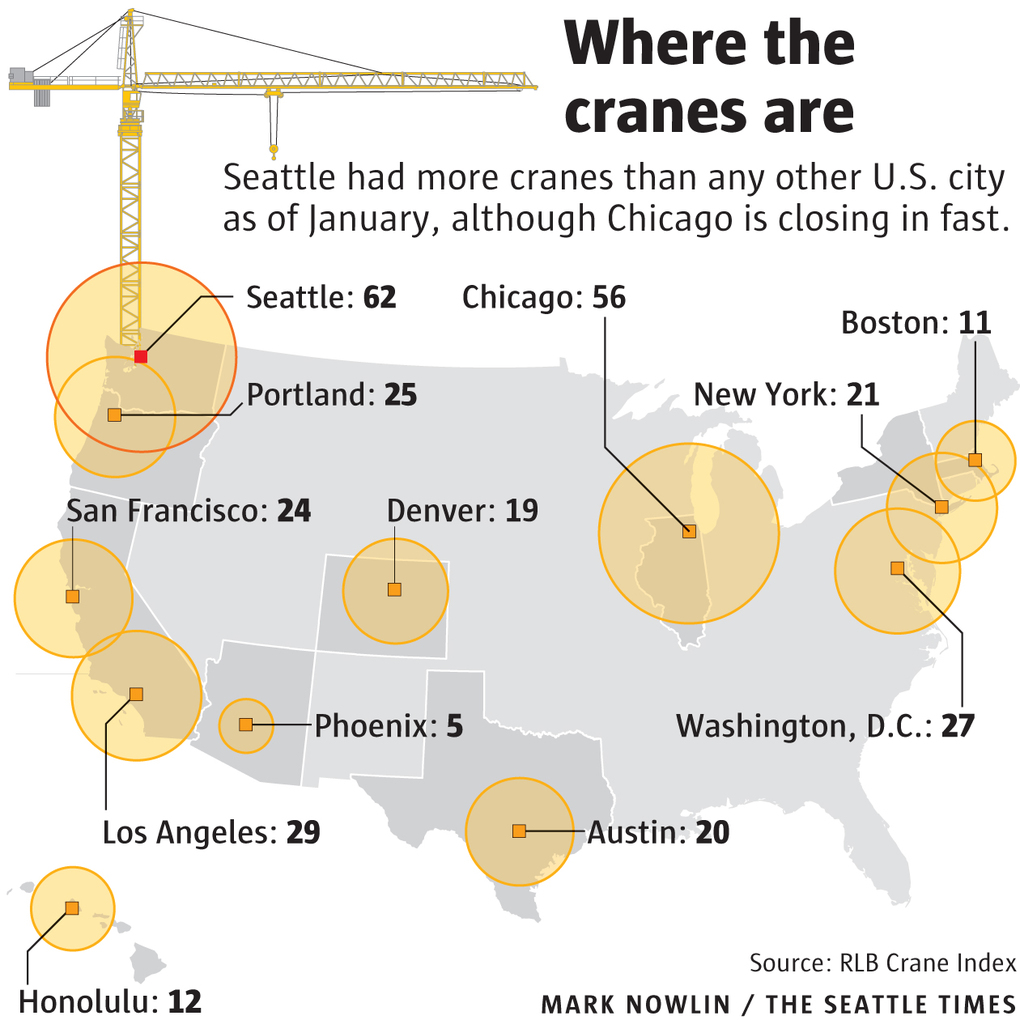

3. The Crane Count. We’re always on the lookout for great urban indicators. Here’s one from the Seattle Times: the count of high rise construction cranes working in leading cities around the country. Its a simple visual indicator of how much central construction activity there is in different cities. Some 62 cranes are currently working in Seattle and 58 in Chicago. Two of the nation’s most expensive (and vertical) markets have many fewer cranes–San Francisco has 24 and New York just 21. They’re currently rivaled by much smaller cities including Portland (25), Denver (19) and Austin (20). One way we’ll cope with our shortage of cities is by building up, and the crane count is one way of tracking where that’s happening.

4. The unintended consequences of inclusionary zoning. Seattle’s in the process of developing a set of inclusionary zoning requirements as part of its Housing Affordability and Livability Agenda (HALA). Sightline’s Dan Bertolet has been crunching the numbers to assess how these requirements will affect the profitability and probability of building new apartments in Seattle. The news isn’t good: for many types of development, the requirements are so costly that its likely that developers won’t go ahead with projects. If fewer market rate units get built, the tenants that would have occupied them will likely end up competing for housing with low and moderate income renters, bidding up the price of existing apartments. Bertolet estimates that losing just one 250 unit apartment building would have the net effect of wiping out about half a year’s progress towards improving the city’s affordable housing supply. While well-intended, a badly designed inclusionary zoning program could easily make the city’s housing affordability problems worse.

New Research

1. Is your smartphone cutting you off from face-to-face interactions? A new study from the University of Milan looks at the connection between smartphone adoption and use and face-to-face interactions and life satisfaction. One of the regular findings of the happiness literature–using survey data on self-reported well-being is that a person’s happiness generally increases with amount of time they spend interacting with friends. Using data from Italy’s version of the general social survey, Valentina Rotondi, Luca Stanca, and Miriam Tomasuolo show that for smart phone users, the positive effect of spending time with friends is significantly reduced.

2. The best city websites. If you’re like us, you’re regularly searching the web for interesting information about cities. Kyle Zheng has compiled a useful and well-organized directory of many of the best sites worldwide. His “Master City” website is organized both by area of interest (placemaking, walkability, sustainability) and had a city-by-city listing of websites.