What City Observatory did this week

1. The death of Flint Street. In Portland, a $450 million dollar freeway widening project is being sold as a way to “re-connect” a community that was divided by freeway construction half a century ago. But there’s a problem with that claim. Part of the project is eliminating one key local street that’s been there since the area was platted in the 1800s, and which today serves as a heavily used segment of the city’s bike network. When asked last week as to why N. Flint Street was being amputated as part of the freeway widening project–the biggest transportation investment contemplated in Portland’s city center–the city’s transportation director simply didn’t know what the rationale was.

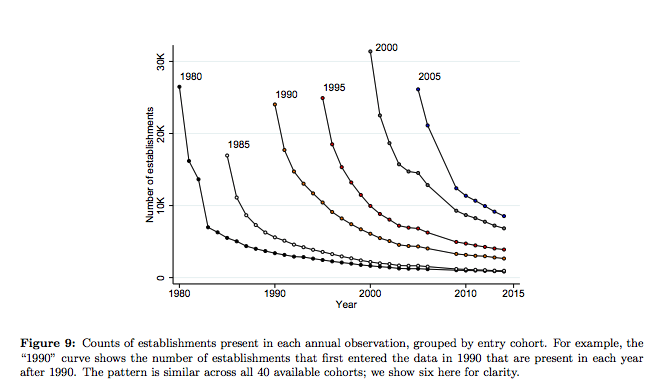

2. Constant change: Turnover in business establishments. It’s natural to think of businesses, particularly larger ones, as long-lived. But as economist Joseph Schumpeter famously observed decades ago, the process of economic growth is one of creative destruction. A recent study sheds some light on the frequency of turnover among largish business establishments. In the US, places that employ 50 or more employees are required to report annually on the racial, gender and ethnic composition of their workforces, and the movement of establishments in and out of that 50 employee threshold is an indicator of how much churn there is in the economy. Over most of the past three decades, about half of the new business establishments that filed in one year were no longer on the register 5 years later–a strong indication of the volatility of the business world.

Must read

1. Public schools shouldn’t undermine walkability. Streetsblog writes another chapter in the long running story of how school siting and development decisions conflict with smart urbanism. Angie Schmidt describes how Decatur, Georgia is building a new elementary school in the as part of to redevelop an underutilized warehousing area as a more vibrant neighborhood (a good thing). Unfortunately,the plan devotes devote most of the site to parking space for buses and the staff’s cars (not so good). The result: they’re tying up a big chunk of valuable land just a five minute walk from the city’s new Avondale MARTA rail station. The site actually devotes more land to parking that similar schools in more suburban locations.

2. High Streets for All. It’s a decidedly English term, high street, but it captures the notion of a pedestrian scaled main street with shops, restaurants and public spaces that are at the heart of urban living. A new report from the London School of Economics catalogs the ways that a vibrant, thriving high street creates the kind of environment that promotes the well-being, social interaction, and economic opportunities of city residents. While the focus is on London neighborhoods–most of which you’ve not heard of–the principles and insights have equal force on both sides of the Atlantic.

3. Declining population in some of Seattle’s most desirable neighborhoods. We’ve all heard stories of how Seattle is in the midst of its biggest population boom since the Gold Rush years (they’re true), but ironically, population is stagnant or actually declining in many of the city’s most desirable neighborhoods. Sightline Institute’s Dan Bertolet marshalls the data. The combination of strict single family zoning in most of the city’s privately owned land, coupled with declining household sizes, especially in higher income neighborhoods, means that actually fewer people live in places like Denny-Blaine, Madrona, and Leschi. Because these neighborhoods hold fewer people, those who might like to live their have to reside further away, adding to sprawl, reducing walkability, and cutting people off from opportunity. The solution? Look for ways to add “gentle density” like accessory dwelling units throughout single family areas, and find at more places that can be upzoned for multi-family dwellings.

New knowledge

A new measure of school performance. One of the most robust correlations in public life is the link between local incomes and kids test scores. Kids who live in wealthier cities or neighborhoods generally have higher test scores than those who live in lower income areas. But a new study, tapping data from the standardized tests used to implement the No Child Left Behind law, sheds new light on how effective schools are in boosting the measured achievement of their students over time. It turns out that many schools in poor neighborhoods actually do a better job than their richer counterparts in lifting student achievement over time. The study was done by Sean Reardon and his colleagues at Stanford, and draws on another trove of big data: this time 11 million test score results from 11,000 school districts around the nation. The New York Times has a powerful interactive graphic illustrating the study’s findings for the nation’s school districts. For example, Chicago Public Schools (which are poorer on average than those nationally), start out with third graders lagging about a year-and-a-half behind the typical third grader nationally. But by the time they reach 8th grade, these Chicago students have closed about two-thirds of the gap with the national average, and are only about six months behind.

What that means is that their schools have essentially accelerated their learning, compared to the average amount of progress made in schools nationally. Nationally, many relatively poor school districts rank considerably higher in raising student achievement over time than do relatively rich school districts. (Hat tip to the estimable Emily Badger and her colleagues at NYT Upshot).

In the news

Inga Saffron, the architecture critic for the Philadelphia Inquirer cited our commentary “Inclusionary zoning has a scale problem,” in her column discussing Philadelphia’s proposed inclusionary housing requirements.

The Portland Mercury quotes the testimony of City Observatory Director Joe Cortright in an article about Portland’s plans to move forward with congestion pricing.