What City Observatory this week

1. Cheap gas means more pollution and more road deaths. Russia and Saudi Arabia have engineered a big decline in oil prices in the past few weeks, and as a result, US gas prices are now expected to decline by about 50 cents a gallon in the coming months. While that sounds like a bargain, we know that cheaper gas translates directly into more driving, more pollution and more crashes. While that will likely be blunted by an economic slowdown because of the disruption caused by Covid-19, the long run effects of cheap gas are negative–the likely fall off in domestic oil production and investment will overwhelm the economic boost from cheaper gas. The decline in oil prices is a great opportunity to do something we should have done long ago: impose a carbon tax.

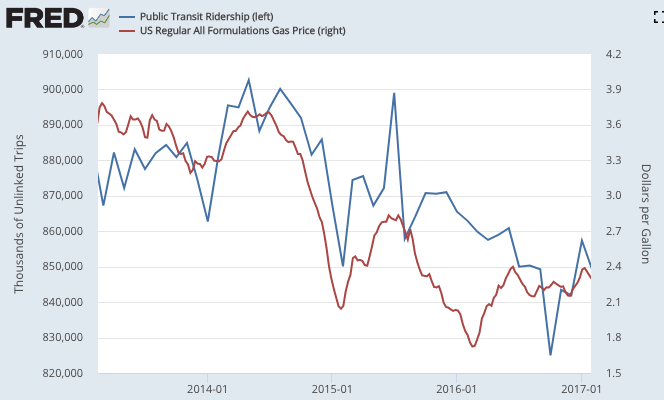

2. It’s no mystery: Bus ridership has declined because gas is so cheap. And its going to get worse. A story in last week’s New York Times posed a widespread decline in bus ridership nationally over the past five years as a mystery. While they line up some interesting suspects (demographics, the changing population of transit-served neighborhoods) they allowed the real criminal to escape scot-free. But we have the smoking gun. The decline in gas prices from 2014 onwards matches exactly the decline in bus ridership.

Its also worth noting that the increase in transit ridership between 2004 and 2013 was propelled by the increase in gas prices; it shouldn’t be any surprise that once gas prices declined that ridership would stop growing, and actually decline. Given oil dropping into the $30 per barrel range, it seems likely that bus ridership is headed for another leg down–and no one should be surprised when that happens.

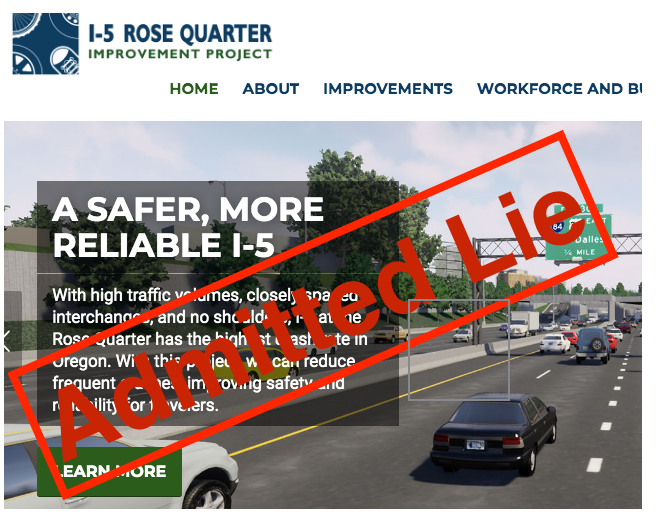

3. The Oregon Department of Transportation finally admits its been lying about I-5 Rose Quarter crash rates. For years, the Oregon DOT has been promoting its now $800 million I-5 Rose Quarter Freeway project with the phony claim that its “the #1 crash location” in Oregon. We and others have been pointing out that’s a lie–based on ODOT’s own statistics–for more than a year. We even provided evidence of this lie in public testimony to the Oregon Transportation Commission–but nothing changed. Until, earlier this month, when we challenged the agency through its “Ask ODOT” email address. The agency finally conceded we were right and removed the false claim from the project’s website–but its still using a false and deceptive claim about safety to sell this wasteful project.

Must read

1. Bill de Blasio, Climate Troll. Charles Komanoff doesn’t pull any punches when it comes to grading Mayor Bill de Blasio’s tenure as Mayor of New York City. While the Mayor gets plaudits from some national enviornmental leaders for promoting divestment and opposing (some) new fossil fuel infrastructure, Komanoff views this as just posturing. When it comes to actual city policies that might reduce the nation’s biggest source of greenhouse gases (driving), and capitalize on the intrinsic greenness of dense urban living, de Blasio is either clueless or missing in action. Komanoff writes:

New Yorkers by the thousands are organizing to win better subways, safe bicycling and vital public spaces — both for their own sakes and because they enable a city with fewer cars. The fossil fuel infrastructure confronting us daily is a hellscape of cars and trucks. Livable-streets advocates are counting down the 22 months left in de Blasio’s second and final term. We’re weary of his inane climate pronouncements and his cluelessness about what being a climate mayor really means.

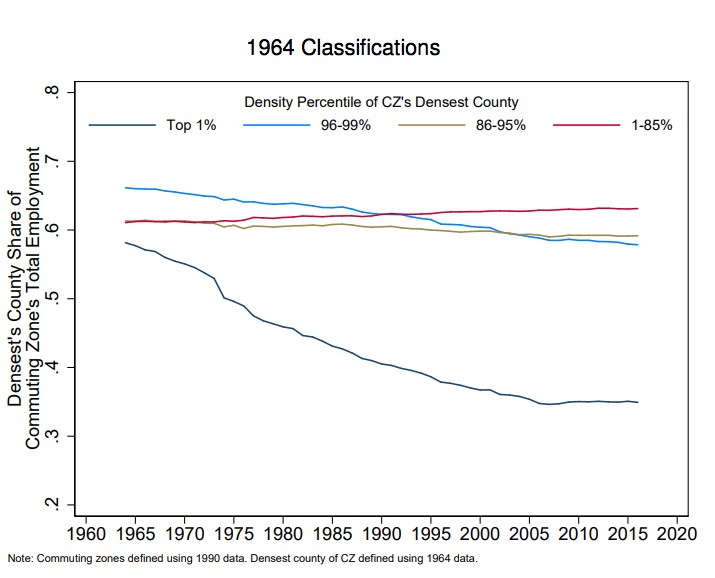

2. Ed Glaeser on “Urbanization and its Discontents.” Just a few years back, Ed Glaeser wrote “The Triumph of the City.” While he’s still bullish on cities (as are we) he recognizes that urbanization, as it is occurring is not an unalloyed good and that there are many things we need to do better to realize the benefits of cities for everyone. Glaeser acknowledges that the private sector dynamics of talent migration and agglomeration are moving faster than the public sector response to a fundamental “centripetal” shift in economic activity. In particular, the politics of cities is now less conducive to growth, especially an expansion of the housing supply in high demand cities. And this in turn has important implications for the nation, blocking the access to opportunity for those with fewer skills, and encouraging a brain drain from less successful areas:

The limits on moving into high wage urban areas also means that migration becomes more selective and that imposes costs on the community that is left behind. When less skilled people can find neither jobs nor homes in high wage areas, then only high skilled people leave depressed parts of the U.S. The selective out-migration of the skilled means that these areas suffer “brain drain” and end up with even less human capital. If local economic fortunes depend on local human capital then this leaves these areas with even less of an economic future.

(Gated working paper available at National Bureau of Economic Research).

New Knowledge

It is easy to forget that the exodus of manufacturing jobs from big cities near the middle of the 20th century caused significant problems both for the affected workers and for the cities themselves. Smaller cities experienced less-severe manufacturing losses during this period, and in some cases substantial absolute increases in manufacturing employment. Our regression analysis indicates that this spatial pattern changed in the 1990s, with outlying manufacturing clusters of counties experiencing large losses as well. The challenges now faced by these more-rural areas closely parallel the challenges faced by New York, Detroit, and other large industrial cities in previous years.

In the News

Rice University’s Kinder Institute republished our thoughts on the Coronavirus pandemic.