What City Observatory did this week

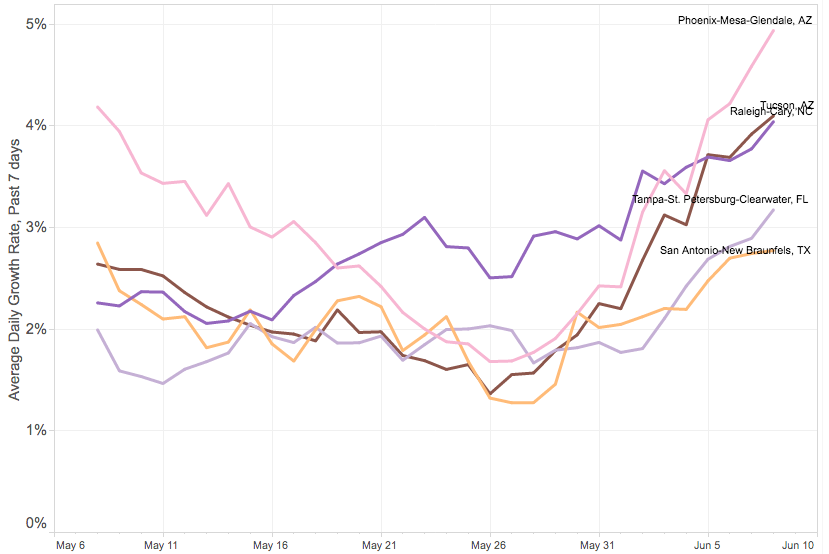

1. Covid-19 rates are spiking in five cities. Stay-at-home policies and social distancing have dramatically slowed the spread of the pandemic in the US, but as many state’s begin re-opening, there’s a concern that the virus could rebound. Looking at the data for the 50 largest US metro areas shows that there’s been a noticeable reversal in the general slowing of the virus in five cities: Phoenix, Tucson, Raleigh, Tampa and San Antonio.

While Arizona’s increase is apparent in statewide statistics, the other three cities have accelerating rates of growth that far outpace the statewide average. We’ll want to pay close attention to what happens in these cities in the next few weeks as a sign of how well we can cope with a second wave of the pandemic.

2. The World Bank’s Sameh Wahba on building inclusive cities after Covid-19. There’s a lot of speculation that the Covid-19 pandemic will undercut the rationale for urban living. But the World Bank’s expert on urban disaster risk management is extremely optimistic that the pandemic will not dim city prospects, and that in fact, the pandemic will be an impetus to building more just places, partly as a way to improve health for all residents, and reduce vulnerability to future viruses.

Cities will continue to attract such footloose population through what they have to offer in terms of livability including quality amenities and services, public spaces and cultural facilities. . . . Cities represent the best of human ingenuity and well-being. That is true today, will be true tomorrow, and well after the pandemic has subsided.

3. Cratering convention centers stick cityies with the bill. We’re pleased to publish a commentary co-authored by former Seattle Mayor Mike McGinn. For the past couple of decades, cities around the country have been competing against one another for slivers of the convention business, subsidizing convention centers, underwriting huge “headquarters” hotels, and even paying conventions to come to town. With the Covid-19 pandemic, the convention business has seized up entirely, slashing room rates and occupancy in hotels, and wiping out much of the room tax revenue cities depend on to pay subsidies.

Among the worst hit places is Seattle, which is the midst of a $1.8 billion expansion of its convention center; unwisely the city put starting construction ahead of nailing down the financing, and now has a huge hole in the center of town, and very little likelihood of being able to sell bonds when room tax revenues have evaporated. It’s a real pickle, but conceals an even deeper problem: the convention center business has been lagging well behind the economy for most of the past two decades.

Among the worst hit places is Seattle, which is the midst of a $1.8 billion expansion of its convention center; unwisely the city put starting construction ahead of nailing down the financing, and now has a huge hole in the center of town, and very little likelihood of being able to sell bonds when room tax revenues have evaporated. It’s a real pickle, but conceals an even deeper problem: the convention center business has been lagging well behind the economy for most of the past two decades.

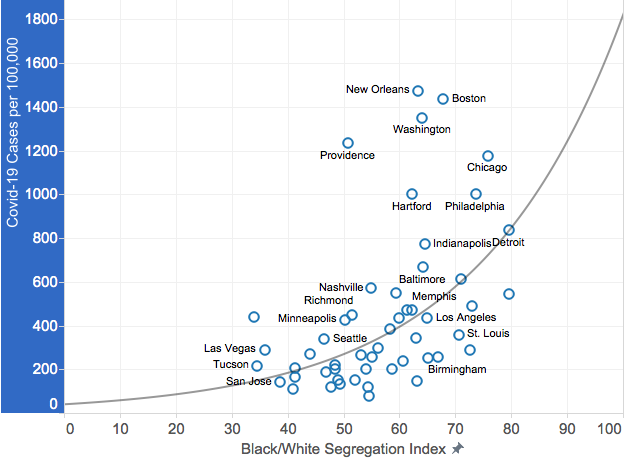

4. Covid-19 in cities: Segregation, not density. There’s been a knee-jerk tendency since the first outbreak of Covid-19 to blame urban density for the spread of the virus. The density theory has been largely debunked, but there’s another aspect of urban form that’s worth considering. We look at the connection between racial/ethnic and income segregation and the prevalence of Covid-19. We’ve known for some time that communities with higher levels of segregation suffer many adverse economic and health effects. The data also show that metropolitan areas with higher levels of black/white segregation and higher levels of income segregation tend to have higher prevalence of Covid-19 on a per capita basis.

Must read

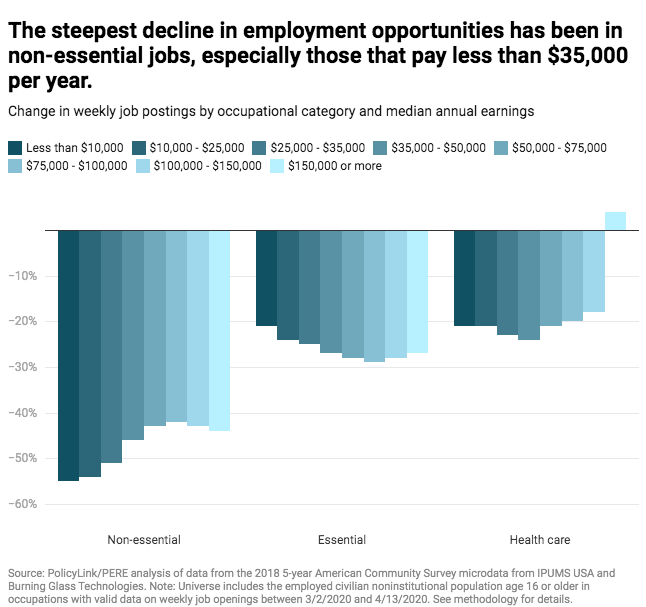

1. The differential impact of the Covid-19 recession on people of color. PolicyLink has a new report looking in detail at the labor market impacts of the pandemic by race and ethnicity. Titled “Race, Risk and Workforce Equity in the Coronavirus Economy,” the report uses a combination of Internet job posting data and Census occupational data to look at the extent of job loss in during the pandemic. Job losses among workers in occupations classified as “non-essential” have disproportionately fallen on low income workers.

The report also finds that in a series of occupations, people of color are more likely to be exposed to the virus. It also finds that job losses in non-essential occupations have been concentrated among people of color.

2. How to respond to the Covid-19 pandemic. The Center for Community Progress has a new report laying out some clear strategic advice for how cities ought to respond to the pandemic. Written by Alan Mallach (author of one of our favorite books, The Divided City), the report begins by sketching out some educated guesses about key aspects of the Post-Covid world: a prolonged recession, many households behind on rent, much tighter markets for housing finance, and badly strapped state and local governments. Mallach estimates that the shortfall in rent payments could be in the range of $29 to $118 billion this year, with effects cascading from families to landlords to the housing market and wider economy.

Some form of rent relief may be a key to reducing pain and staving off further economic decline. Ultimately, only the federal government has the resources necessary to make a material difference. Assuming we can generate an effective response, Mallach challenges all of us to think more expansively about how we might use this crisis as an opportunity to build better, stronger communities:

Can we see the challenge of recovering after the pandemic as an opportunity to rebuild not the same, but better than we were?

3. Don’t write off downtowns. Seattle Times business columnist Jon Talton is still very bullish about downtowns–at least his downtown, even in the wake of the Covid-19 pandemic. Cities just have too many economic advantages not to bounce back. He writes:

Today, downtowns continue to offer unique advantages in efficiency, productivity and innovation. They are the places where “creative friction” happens as ideas are easily shared and serendipitous encounters happen. They offer public spaces and cultural amenities for all. In Seattle, large numbers of low-income housing units are sustained here, too. In an era where the greatest challenge is climate change, downtowns served by abundant, frequent and convenient transit are essential to reducing greenhouse gases.

New Knowledge

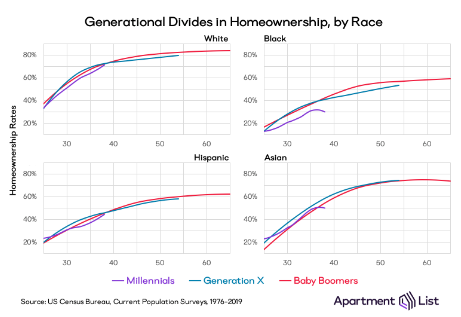

Generational shifts in homeownership rates. ApartmentList’s Rob Warnnock carefully dissects the homeownership statistics by age, generation, income, education and race and ethnicity, to trace out the shifting patterns of homeownership in the US. The core finding, as we’ve seen before, is that homeownership rates are declining with each successive generation:

Homeownership in general has been on the decline for at least the last three generations. After adjusting for age, millennials, gen Xers, and baby boomers have all purchased homes at a slower rate than the generation that preceded them.

While that’s been established for some time, this report sheds light on the interesting sub-trends among different demographic groups. Perhaps not surprisingly, homeownership rates for whites have not declined nearly as much as for other racial and ethnic groups, after controlling for age and generation.

Overall homeownership rates are down far more for the entire population than any individual racial/ethnic group. What’s driving the decline then, is the increasing diversity of the US population, and in particular the fact that much of the growth is in among groups (Hispanic and Black) who have lower homeownership rates. This suggests that raising homeownership rates (to the extent that is a worthy policy objective) depends on reducing this persistent racial gap.

Rob Warnock. “Homeownership rates by generation: How do Millennials stack up?’ ApartmentList.com, March 17, 2020.

In the News

City I/O published its summary of our report, America’s Most Diverse, Mixed Income Neighborhoods.