What City Observatory this week

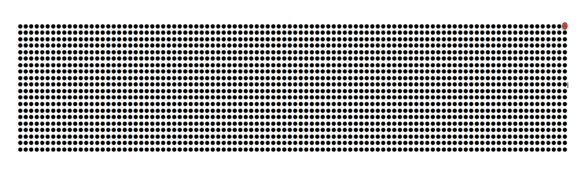

1. A massive regional transportation spending plan that does nothing for climate change. Portland’s leaders are in the process of crafting a $3 billion plus regional transportation package. One of its stated objectives is to help reduce greenhouse gas emissions. But a recently released staff analysis shows the multi-billion dollar plan will lower greenhouse gas emissions by just 5,200 tons out of a regional total of more than 9.5 million. That works out to a five one-hundredths of one percent reduction. Graphically, something like this:

What’s particularly alarming is that Portland’s greenhouse gas emissions from transportation have been growing rapidly since the collapse of oil prices in 2014, with the region emitting 1.6 million more tons of greenhouse gases now than in 2013; The entire multi-billion dollar package will offset just a couple of days worth of the growth in emissions. If the region is serious about climate change, its going to need something very different from this package.

2. When it comes to climate change, it’s always Groundhog’s Day. We seem to be stuck in an infinite loop when it comes to climate policy. We adopt bold declarations that we’re going to reduce our greenhouse gas emissions . . . someday. But when we look at the latest accounting, well, it turns out that we’re not making any progress, and when it comes to greenhouse gases from transportation, we’re making things worse, almost entirely because we’re driving more. We highlight the continuing–and growing–disconnect between the high minded rhetoric (and much celebrated long-term goals) that Oregon and other states have adopted for climate change, and the actual progress, which has been not just nil, but negative, when it comes to transportation. If we’re serious about climate change, we’re going to have to do something different, or next Groundhog’s Day is going to look pretty much the same.

Must read

1. The optimal serendipity of industry clusters. Rents near Kendall Square in Cambridge are pushing $100 per square foot, making it one of the most expensive places to locate your business. Yet biotech businesses willingly pay these high rents, rather than relocating to cheaper suburbs (or one of the many cities questing to be a biotech center). Why? Well, as economist Robert Lucas opined three decades ago, people pay high rents in cities, and places like Kendall Square, to be near other people. The Boston Globe recites first-hand accounts of the benefits that researchers, industry executives, venture capitalists, and other biotech specialists reap from being in close proximity to thousands of their peers. Some of this is the straightforward benefits of propinquity, its easier and quicker to connect with just the expert you need. But a big part of the benefit is serendipitous interaction, things you learn from the random accidents of who you encounter. This source of cluster competitive advantage is over-whelming and almost impossible to duplicate, which is why calls to spread innovation based industries more evenly across the landscape are almost certainly doomed to fail.

2. Grand strategy for housing affordability. The re-legalization of four-plexes in Oregon and triplexes in Minneapolis represent an important symbolic victory in the effort to restore housing affordability in the nation’s cities. But Sightline Institute director Alan Durning argues that its just a first step in a much longer and more difficult effort to reshape housing policy.

Durning compares the housing debate to World War I’s continental scale trench warfare, and while hopeful, the advances in “missing middle” housing are just a mile long incursion in what amounts to a thousand-mile front. We raised much the same concern in our 2019 commentary: You’re going to need a bigger boat. While triplexes and fourplexes are a step in the right direction, its only a beginning. As Durning says:

And they are breakthroughs. They have few precedents in recent decades of local housing law on this continent: the sanctum of single-family zoning has been breached. But viewed from a broader perspective, they are breakthroughs in a war we are losing. Or at least, a war we’re winning so slowly that we might as well be losing.

This commentary steps back from the policy tactics of local and state legislation to consider the broader political map on which housing debates turn. Advancing from the current breakthrough is going to require new and stronger political coalitions. Durning promises to explore new political strategies that will help build the case for affordable, low carbon cities. We’ll follow this with interest.

3. There’s no shortage of housing–for cars. Streetsblog Boston has a fascinating analysis of new housing developments in Boston. The good news? The city is building more housing, and doing so in transit served locations. The bad news: The housing developments have a huge amount of parking. In the 27 projects permitted in the past year, there are 1,984 housing units and 2,152 parking spaces–more than 1.1 per unit. That parking tends to be expensive, more than $25,000 per above ground parking space, (making housing less affordable), and according to careful studies, also tends to be underutilized (even at peak occupancy, 30 percent of parking spaces remain un-used). Boston’s climate goals call for more housing and less driving, but the way real estate is getting developed, car dependence is built in to new housing.

New Knowledge

How green are electric cars? A defining feature of the electric car is the absence of a tailpipe. That leads some to conclude that electric vehicles are completely green or “zero emission,” but that misses the fact that both the car (and importantly its battery) require energy for manufacturing, and the electricity that the car uses has to come from some other sources of energy. If your Tesla gets charged up with electricity from a coal-fired power plant, its decidedly less green than if it draws its electricity from a windmill or solar cells. And the same with its battery: battery manufacturing requires a fair amount of electricity, so whether the battery factory is in China, for example, where most electricity comes from coal, it will have a substantial carbon footprint.

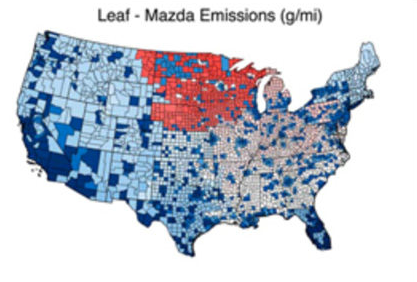

There are plenty of dueling studies out there estimating the greenhouse gas emissions from electric cars compared to traditional internal combustion engines and hybrid vehicles. One study compares the life-cycle greenhouse gas emissions of a battery-powered plug-in Nissan Leaf with a Mazda 3, a similarly sized vehicle powered by a conventional internal combustion engine. The following map shows the results, with the areas shown in blue being places where the Leaf has lower emissions, and red showing places where the Mazda has lower emissions. The difference reflects the relatively high use of coal for electricity generation in the Northern Plains States.

As Prof Jeremy Michalek, director of the Vehicle Electrification Group at Carnegie Mellon University, tells Carbon Brief, “which technology comes out on top depends on a lot of things”. These include which specific vehicles are being compared, what electricity grid mix is assumed, if marginal or average electricity emissions are used, what driving patterns are assumed, and even the weather.

Electric cars have the potential to reduce greenhouse gas emissions, but as this study suggests, when and where they are deployed, and how rapidly we can de-carbonize electricity generation are important factors in determining the role they should play in any climate strategy.