What City Observatory this week

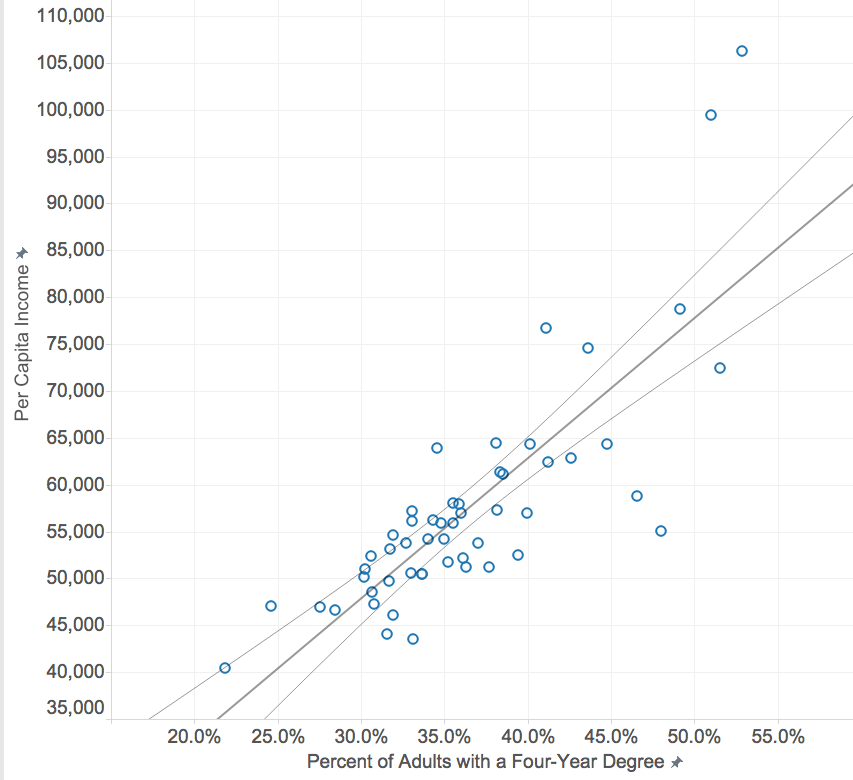

1. Talent drives economic development. We know the single most important factor determining metropolitan economic success: It’s determined by the education level of your population. The latest data on educational attainment and per capita incomes show that two-thirds of the variation in income levels among large metro areas is explained by the fraction of the adult population with a four-year degree.

Each one percentage point increase in the adult college attainment rate is associated with a $1,500 increase in metro average per capita income.

2. Jealous billionaires and cash prizes for bad corporate citizenship. The big economic development prize of the past several years was Amazon’s HQ2, which the e-commerce giant purposely structured as an competitive extravaganza, baldly asking for subsidies from cities across North America. Bloomberg Business reports that Amazon’s quest was fueled by CEO Jeff Bezos’s jealousy over the generous subsidy package Nevada provided Elon Musk for a Tesla battery factory.

3. It works for bags, bottles and cans, why not try it for carbon? A newly enacted law in Portland requires grocery stores to charge customers a nickel for each grocery bag they take. Echoing Oregon’s half-century old bottle bill, and similar bag fees in other places, this provides a gentle economic nudge to more ecologically sustainable behavior. And the evidence is that it works–it London, single use bags are down 90 percent. We ought to be applying the same straightforward logic to carbon pollution, and ironically, the bag fee, on a weight basis is 20 times higher than the charge most experts recommend for carbon pricing.

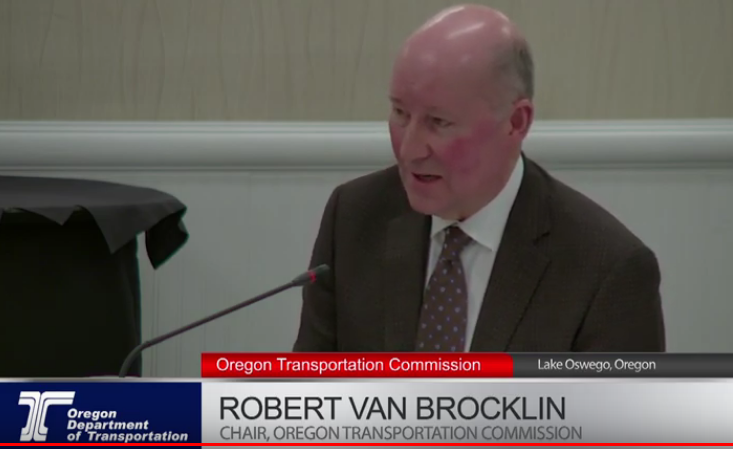

4. Dodging responsibility for climate change. Oregon’s Transportation Commission, a five-member citizen body, is on the firing line in the battle on climate change because of its plans to spend $800 million to widen a Portland freeway. It has largely turned a deaf ear to testimony about the freeway’s negative effects, essentially asserting that the decision to build the freeway has already been made by the Legislature. They’re just following orders, apparently.

In our view, that’s far too narrow a view of the Commission’s role and responsibility: they have an obligation to hear citizen concerns, and if the project is unsustainable, uneconomic, and won’t work, they have a duty to tell the Legislature.

Must read

1. Fighting housing segregation in Baltimore. CityLab has a great retrospective on the struggles in Baltimore to break down the segregation of public housing. As in many US cities, for decades, public housing (which disproportionately serves people of color) has gotten built in low income neighborhoods, which has only served to perpetuate and intensify racial and income segregation. CityLab chronicles the role of Barbara Samuels, and ACLU lawyer who challenged this practice, and who won a court victory 25 years ago. This court case–Thomspon v. HUD, gave some real teeth to the Fair Housing Act’s provisions requiring governments to affirmatively further fair housing. Ultimately this case got housing officials to instead implement a system of housing vouchers that give public housing recipients the opportunity to live in middle income and higher opportunity neighborhoods.

2. Little Women’s lessons for housing policy. It takes a real wonk to find deep housing policy lessons woven through an Academy Award nominated film, and Brookings Institution scholar Jennie Schuetz is up to the task. Little Women features a combination of mixed income neighborhoods, relaxed building codes, and co-housing (boarding houses) all of which facilitate greater housing affordability–and thanks to social mixing–romance. As Schuetz explains:

Less zoning equals more social equity and more romance. While some details of the world depicted in “Little Women” would not appeal to modern audiences—corsets and the lack of modern health care come to mind—a more laissez-faire approach to housing regulation seems worth revisiting. Can we imagine a return to communities where mansions, middle-class homes, boarding houses, and low-income housing can co-exist without legal restrictions or social prejudice? Where households with diverse incomes and family structures can interact with casual, everyday intimacy?

In spite of 21st Century injunctions about lesser income housing lowering home values and the apparent desirability of ubiquitous homeownership, the lifestyles (and policies) of 19th Century America promoted housing affordability and social mobility, things we could use more of today.

3. Boston’s under-occupied large homes. We often talk about a shortage of housing, but in an important sense, the problem is less a shortage than a maldistribution. A new study from the Metropolitan Area Planning Council, Boston’s regional planning agency looks at the occupancy of large dwellings (those with three or more bedrooms). It finds that most are under-occupied–that is, these housing units have fewer occupants than they do bedrooms. This phenomenon is driven by history, homeownership, and demographics. A quarter of all three bedroom units are occupied by just one or two persons aged 55 or older. Inertia, the transaction costs associated with selling a home, and a probable lack of smaller ownership opportunities for those who want to age in place (or very nearby) likely contribute to older homeowners staying in these larger houses, rather than selling them to younger and larger households. The mismatch between household sizes and housing units suggests that part of the solution to our perceived housing shortage would be to develop incentives for older homeowners to downsize more quickly.

New Knowledge

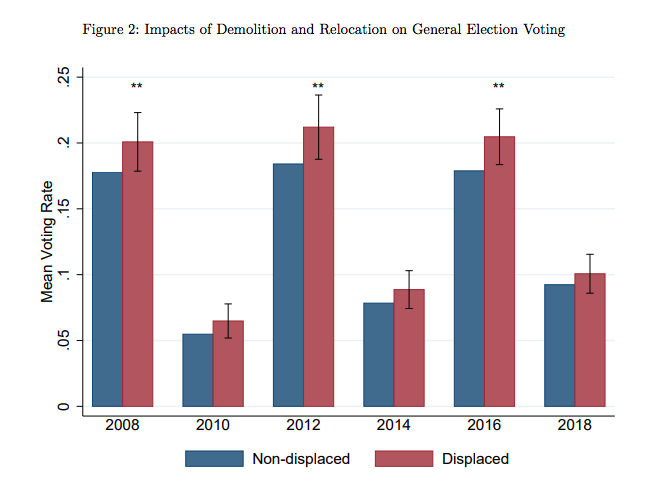

Integration and civic engagement. A growing body of evidence points to the importance of mixed income neighborhoods to the lifetime economic prospects of kids from low income families. A new study from xxxx shows that growing up in mixed income neighborhoods also seems to encourage greater civic participation. Eric Chyn, who looked at the economic outcomes from kids from families given vouchers to enable them to move out of low income neighborhoods in Chicago, has a new study looking at effects on voter participation. His key finding: kids who grew up in these more mixed income neighborhoods tended to have higher voting rates as adults that otherwise similar peers who grew up in lower income neighborhoods. On average, kids growing up in mixed income neighborhoods were about 12 percent more likely to vote as adults than their peers.

Eric Chyn & Kareem Haggag, Moved to Vote: The Long Run Effects of Neighborhoods on Civic Participation, University of Chicago, Human Capital and Economic Opportunity Global Working Group, Working Paper #2019-079, 2019.