What City Observatory this week

1. Oregon DOT repeats its idle lie about emissions. It’s every highway builder’s go-to response to climate change: we could reduce greenhouse gas emissions if we could just keep cars from having to idle in traffic. That turns out to be a great way to rationalize any highway-widening project. Which is exactly why new Oregon Department of Transportation Director Kris Strickler invoked this claim in his recent confirmation hearing. But its also the case that its an utterly unfounded urban myth that making cars move faster will reduce carbon pollution. Just the opposite, in fact. Measures that speed cars (whether additional lanes, better signal timing, or “improved” intersections) just prompt more people to drive. It’s this induced demand effect–now so well-demonstrated that its call the “fundamental law of road congestion”–more than wipes out any gains from lower idling. More and longer car trips, not time spent idling, are what cause increased greenhouse gas emissions.

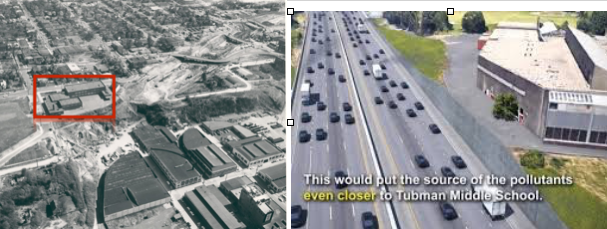

2. A long history of highway department ignoring school kids. The latest objection to the Oregon Department of Transportation’s Rose Quarter freeway widening project comes from the Portland School Board, which has voted to ask for a full-scale environmental impact statement for the $500 million project which moves the I-5 freeway even closer to the Tubman Middle School. The district has already had to spend millions on air filtration equipment to make the school habitable; a wider freeway with more traffic would likely increase the impact on kids, and an array of new studies are showing long term damage to learning from chronic exposure to auto pollution. But if history is any guide, the school board seems likely to be ignored. Six decades ago, its predecessors raised very similar objections to the original siting of the freeway next to the school, and despite assurances from city and state officials that their concerns would be addressed, the freeway was built exactly as planned, slicing off part of Tubman’s school yard, bisecting attendance areas for other nearby schools, and dead-ending dozens of neighborhood streets. Of course, in the early sixties, there was no National Environmental Policy Act, and no one knew for sure how harmful pollution was. Will this time be different?

Must read

1. Climate-talking mayors are inexplicably building more freeways. We’ve long noted the discrepancy between the bold climate rhetoric of some Mayors and their political support for more and wider freeways. Curbed’s Alissa Walker lists progressive cities around the country, including Los Angeles, Houston, Portland, Austin, Chicago and Detroit who are planning to spend billions to widen freeways, in spite of their Mayor’s ostensible pledges to be moving to reduce carbon pollution. Walker writes:

. . . climate mayors are currently allowing massive expansions of highway infrastructure in their cities. There are at least nine major highway-widening projects with costs totaling $26 billion proposed or currently underway in U.S. metropolitan areas governed by members of the Climate Mayors group.

As Brent Toderian has frequently said, if you want to understand someone’s real priorities, look at their budget. The spending priorities of these ostensible climate leaders shows that their actual priorities really aren’t very concerned about the climate crisis.

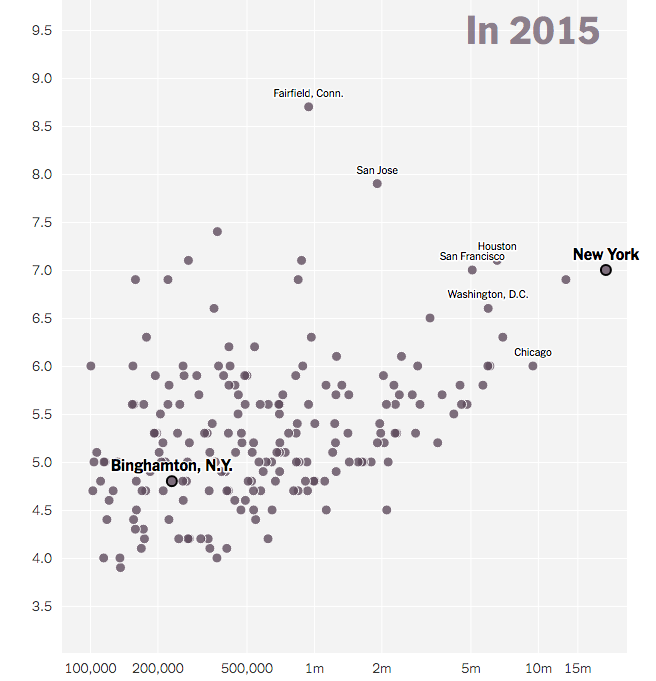

2. Inequality has gotten worse in almost every city–maybe inequality isn’t a local problem. Emily Badger and Kevin Quealy of The New York Times have a nice visualization of the growing wage inequality experienced in almost every US city over the past four decades. Their animation shows that the gap between the 90th percentile wage and the 10th percentile wage; i.e. the difference between the average hourly earnings of the person at the bottom of the top ten percent of all wage earners and the average hourly earnings of the person at the top of the bottom ten percent of all wage earners. In most metro areas, the 90th percentile worker earned about four times as much as the 10th percentile worker in 1980; by 2010, this had increased to five to six times times as much in 2015.

As we know, changes at the top and bottom of the wage distribution have accounted for this gap. Some high paid occupations and industries have recorded much higher than average increases in wages. Conversely, at the low end of the labor market, the minimum wage has failed to keep pace with inflation. While the levels of wage inequality vary across metropolitan areas, the striking point here is that wage inequality has increased almost everywhere, suggesting that a common set of national factors, rather than principally local ones, are behind growing inequality.

3. Brookings calls for a fundamental re-thinking of federal infrastructure policy. Everyone seems to agree that “infrastructure” is really important to the economy and the environment, but beyond glib generalities, there’s a world of nuance that makes all the difference. The Brookings Institution has a new report calling for re-visiting of the first principles guilding infrastructure. A big part of our current problems–especially climate change, and economic segregation–are a product of the kinds of investments we’ve made in infrastructure. More of the same–more freeways, more far-flung sewer and water systems and so on, are likely only to exacerbate sprawl and create more car dependence. As the report’s lead author, Adie Tomer writes:

Current infrastructure networks and land uses make our climate insecurity worse. The transportation sector is now the country’s top source of greenhouse gas emissions, representing 29% of the national total. The country continues to convert rural land into urban and suburban development faster than overall population growth, leading to greater stormwater runoff, higher fuel consumption, and accelerated loss of tree cover, wetlands, and other natural resources.

The default political trajectory for infrastructure is simply to plow more money into existing programs, like the highway trust fund, that simply repeat the mistakes of the past. Brookings is calling for a careful look at how we change the framework and incentives around our infrastructure investment to align with the challenges we now face, particularly the climate crisis and growing inequality. That conversation is long overdue.

New Knowledge

Food deserts? Fuggedaboutit. One of the most popular urban theories of the past decade or so has been the notion of food deserts, the idea that low income households have poor nutrition because they don’t have local stores that sell healthy food. The policy implication has been taken to be that if we could just get more healthy food closer to low income households, their health status would improve.

A recent study from six economists uses some extremely rich and detailed data on consumer spending patterns, and traces the effects of the opening of new supermarkets on the buying patterns of nearby residents. It finds, contrary to popular belief, that significant changes the the local array of “good foods” have almost no effect on the buying patterns of nearby residents. For example, the entry of a new supermarket into a food desert tends to reduce sales at other nearby supermarkets, rather than shifting the composition of consumer spending away from less healthy stores (like convenience stores).

The authors show that there are strong correlations between income and education, and the propensity of consumers to purchase healthier foods. By their estimates, only a tiny fraction of the variation in healthy food consumption is explained by supply-side factors (i.e. proximity to stores with healthier food).

Entry of a new supermarket has economically small effects on healthy grocery purchases, and we can conclude that differential local supermarket density explains no more than about 1.5 percent of the difference in healthy eating between high- and low-income households. The data clearly show why this is the case: Americans travel a long way for shopping, so even people who live in “food deserts” with no supermarkets get most of their groceries from supermarkets. Entry of a new supermarket nearby therefore mostly diverts purchases from other supermarkets. This analysis reframes the discussion of food deserts in two ways. First, the notion of a “food desert” is misleading if it is based on a market definition that understates consumers’ willingness-to-travel. Second, any benefits of “combatting” food deserts derive less from healthy eating and more from reducing travel costs

If we’re really concerned about nutrition, the author’s argue that some strategic changes to the SNAP (supplemental nutrition assistance program, long called Food Stamps) might be a more powerful way to encourage consumers to make healthier choices. Right now, SNAP provides the same subsidy for low nutrition foods as high nutrition foods; a system that lowered or eliminated subsidies for the least nutritious foods and increased them for the most nutritious foods would generate healthier purchases.

Hunt Allcott, Rebecca Diamond, Jean-Pierre Dubé, Jessie Handbury, Ilya Rahkovsky, and Molly Schnell, Food Deserts and the Causes of Nutritional Inequality, NBER Working Paper No. 24094

In addition to the technical working paper, the lead authors have published a short, eminently readable non-technical summary of their findings at The Conversation.

In the News

Willamette Week and BikePortland highlighted our debunking of Oregon Department of Transportation official claims that wider freeways will reduce greenhouse gas emissions.