What City Observatory did this week

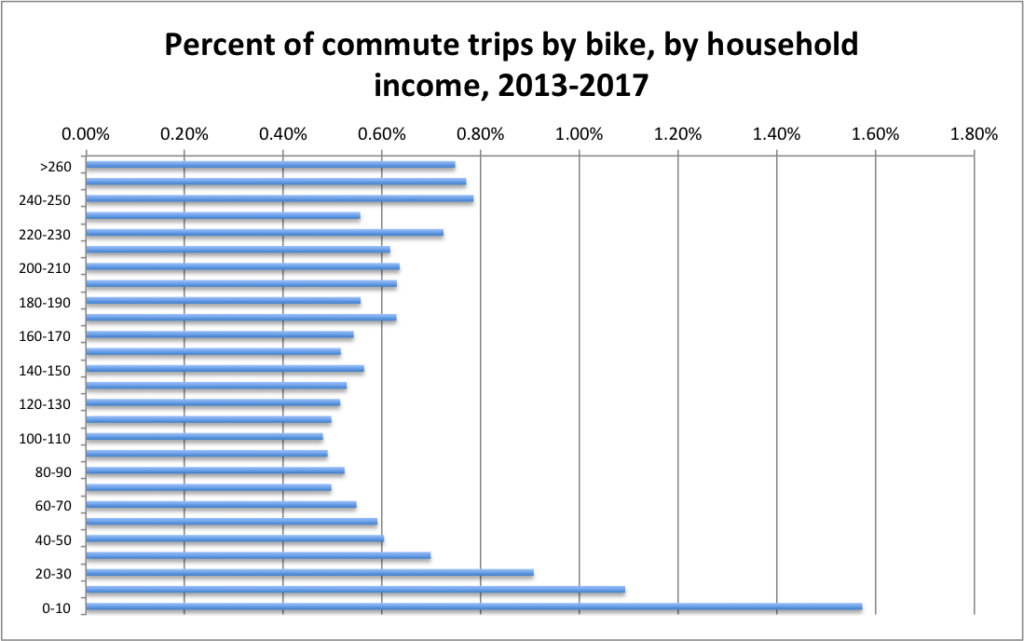

1. Who bikes? Discussions of investing in bike infrastructure are often fraught with arguments about who benefits, with oft-expressed fears that bike lanes chiefly benefit a spandex-wearing elite. How does cycling correspond to income. There’s a misleading claim floating around the twitterverse that the single largest group of bike commuters is from households earning less than $10,000 per year. That’s not correct, but our analysis of the most recent census data on daily journeys to work shows that it is actually the case that workers lower income households are more likely than most American’s to commute by bike. Those earning less than $10,000 are about three times as likely to be bike commuters than the typical worker. In general, the more income you have, the less likely you are to commute by bike. While there is a slight uptick in bike commuting for those from households with incomes of more than $100,000, workers from high income households are still much less likely to commute by bike than workers from low income households.

2. The constancy of neighborhood change. There’s a subtle bias in the way we talk about neighborhood change. Many discussions seem to assume that neighborhood populations are fixed, and un-changing, and that absent some dramatic external event–like gentrification–they’ll tend to stay just as they are. But all neighborhoods are constantly changing. We review a recent study that looks at the dynamics of population change in neighborhoods and finds:

- The population of urban neighborhoods is always changing because moving is so common, especially for renters.

- There’s little evidence that gentrification causes overall rates of moving to increase, either for homeowners or renters.

- Homeowners don’t seem to be affected at all, and there’s no evidence that higher property taxes (or property tax breaks) influence moving decisions.

- While involuntary moves for renters increase slightly in gentrified neighborhoods, there’s no significant change in total moves

For most neighborhoods, the question isn’t whether they’ll change, but how. As we noted in our study, Lost in Place, high poverty neighborhoods that didn’t improve materially hemorrhaged population, losing 40 percent of their residents over four decades.

Must read

1. Updating London’s Congestion Charge. For the past two decades, London’s central area-congestion charge, a fee charged for vehicles crossing a cordon in Central London, has been hailed as one of the pioneering efforts to priced congested urban roads. The charge has helped moderate traffic entering the central area, and provided funding to improve transit. But the charging scheme, which is based on decades-old technology, and which is riddled with exemptions, is, in that quaint British-phrase “no longer fit for purpose.” Or so argues a new report from the Centre for London, which calls for updating the congestion charge, and integrating all of the systems for paying for urban transportation. Under their proposal, payment for car travel on city roads would be combined with charges for public transit (i.e. the current Oyster card), with all private vehicles paying per kilometer of travel, and with charges varying according to place and time of travel.

Our fundamental recommendation is for London to move to a more sophisticated and comprehensive distance-based road user charging scheme, closely integrated with the rest of the capital’s transport system. The aim would be to replace the various charges currently spreading across the city with a single scheme that reflects all impacts of a journey. The scheme, which would apply to all motor vehicles every day and at all times, could be extended gradually, with charges first applied only to the most congested and polluted areas of the city. In return for any charge 16 incurred, drivers would benefit from improved traffic flow and journey time reliability, enabling TfL to offer a guaranteed level of service and potentially refunds for excessive journey delay – on the same model as ‘delay repay’ for trains. All funds raised would go back into maintaining and investing in London’s roads and streets, public realm and public transport.

2. German economists urge road pricing in cities to reduce pollution and congestion. The widespread adoption of diesel vehicles has aggravated urban air pollution in Germany, and some cities are responding with bans on polluting vehicles. A group of German economists argues that banning some vehicles (while allowing others, like electric vehicles) is unfair to those who can’t afford cleaner transport, and is inefficient. Instead, they’ve urged German cities to set up road pricing systems which would allow everyone to access city centers by vehicle when they needed to, provided incentives for lower pollution travel. Revenue from the charge could be used to improve public transport services, cycling infrastructure and subsidize less affluent citizens in using cleaner transport modes. They write:

. . . a city toll, i.e. a charge for using a car in the city, would be the socially fairer and economically much more sensible alternative. More environmentally friendly and traffic-relieving alternatives to cars would become more attractive and municipalities could benefit from additional revenues. [And] nobody who needs to rely on car transport would be banned from driving in the cities.

Hat tip to the Clean Energy Wire.

3. We used to do this everywhere. Strongtown’s Daniel Herriges has just returned from a visit to New Orleans French Quarter and asks a question that’s always been top of mind for us: How have we forgotten how to build great urban spaces? Walkable, interesting, human scale settlements are so rare that they’ve become tourist-saturated anomalies. Why, if with the much lower incomes (and public infrastructure budgets) of the 18th century were we routinely able to build such places, and yet we find it impossible to build them today? Herriges points out that attributing the urbanity of the French Quarter to the french is a bit of a misnomer, as the design principles for New Orleans were handed down largely in the era of its Spanish governance, when the colonial “Law of the Indies” prescribed development patterns. Those rules, which were applied throughout Spanish colonial America laid out cities in a familiar pattern, with a central square, usually bordered by important public buildings, a grid of surrounding narrow streets offset from the North-South axis to maximize shade. Those principles are apparent today in cities in Latin America, as well as in older cities in the US Southwest. This story reminds us of the importance of land use planning: just as the maxims of the Law of the Indies produced enduring walkable spaces, our current land use laws which widely separate land uses, mandate parking and building setbacks, and build infrastructure primarily to expedite car movement and everywhere produced spaces that are as thoroughly hostile to human enjoyment as these older towns were (and are) conducive to it.

New Knowledge

The health of the air. While we’ve made substantial progress over the past several decades, air pollution remains a major health challenge in many US cities. New York University’s Marron Institute has a new report on the health effects of two key sources of air pollution: fine particulates and ozone. The good news is that we’re continuing to make progress in reducing fine particulate matter, with the number of estimated deaths from this source of pollution declining from about 12,000 per year to about 6,000. But we’ve made less progress on ozone, and despite overall improvements, both forms of pollution are still disproportionately severe in some locations. The Marron Institute report flags these hot spots with data and maps for states and metropolitan areas the levels of fine particulates (particles smaller than .25 mm) and ozone, and the number of deaths and illnesses associated with pollution.

Among US cities, the health effects of fine particulates are most severe in Southern California, with Los Angeles, Riverside and Bakersfield ranking first, second and third in most excess deaths per capita from this pollutant. Los Angeles and Riverside also top the list for most excess deaths associated with ozone.

Among US cities, the health effects of fine particulates are most severe in Southern California, with Los Angeles, Riverside and Bakersfield ranking first, second and third in most excess deaths per capita from this pollutant. Los Angeles and Riverside also top the list for most excess deaths associated with ozone.

Marron Institute, Health of the Air, 2019, (https://healthoftheair.org/)

In the News

Writing at CityLab, Richard Florida laid out his take on the ongoing debate about whether upzoning cities would help improve housing affordability, quoting City Observatory’s argument that answered that question strongly in the affirmative.