What City Observatory did this week

A note to City Observatory readers: We’re deep in the thick of Portland’s debate about whether to spend a half billion dollars to widen a mile-long stretch of freeway near the city’s downtown. Based on all we’ve learned in our research at City Observatory, and our analysis of the project, we think its a signal example of the application of failed highway engineering practices that are likely to seriously damage a rebounding neighborhood in a thriving city. We think there are broad lessons for cities around the country, and so this week and next, we’ll be devoting most of our coverage to an in-depth examination of the project and its implications. Our regularly scheduled Week Observed features, “Must Read” and “New Knowledge” will return next week.

1. How sales tax avoidance creates traffic congestion in Portland. No two states have more different tax systems than Oregon and Washington State. Washington has one of the nation’s highest sales tax rates, over 8 percent, while Oregon has no general sales tax. In the Portland metropolitan area, the only thing that separates residents of Vancouver Washington from tax free shopping is the Columbia River, which is spanned by just two bridges, carrying Interstates 5 and 205. We estimate that residents of the Vancouver area spend about $1.5 billion a year on goods and services purchased in Oregon that would otherwise be taxable in Washington State, saving them a total of about $120 million a year in state and local sales taxes. But the steady flow of Washington shoppers to Oregon stores imposes its own toll on the region’s freeway system. We estimate that 10 to 20 percent of the traffic on the two bridges across the Columbia River consistents of tax avoiding Washington shoppers–that’s enough to be a measurable contributor to the region’s traffic congestion problems. Time-varying congestion pricing of I-5 and I-205–which has been approved by the Oregon Legislature–would likely prompt large numbers of these shoppers to change the timing of their shopping trips to avoid peak hours, with beneficial effects on traffic congestion.

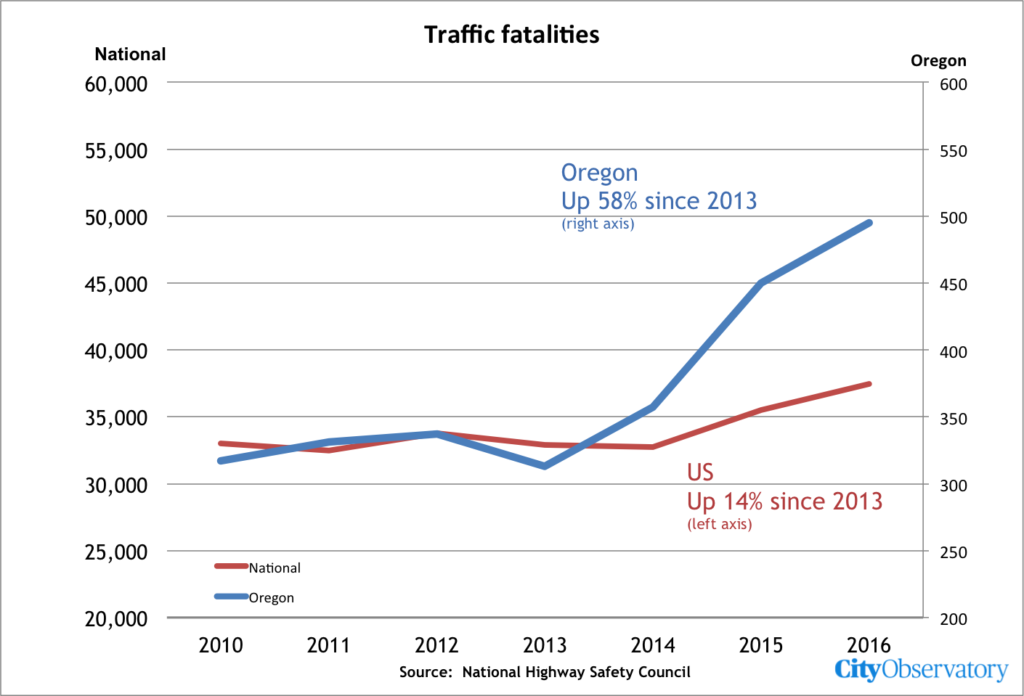

2. Using the Big Lie to sell freeway widening. Fear-mongering is a time tested sales tactic, and it’s very much in play in the efforts of the Oregon Department of Transportation’s efforts to sell a half-billion dollar widening of Interstate 5 near Portland’s Rose Quarter. ODOT’s staff and consultants have a frequently repeated talking point that this stretch of freeway is the “#1 crash location” in Oregon. It’s a scary, but utterly false claim. The agency’s own safety data show crashes on other ODOT managed highways in Portland are two to five times higher. More important, the freeway crashes are overwhelmingly non-injury fender-benders; in contrast the crashes on state-run arterials like 82nd Avenue, Barbur Boulevard and Powell Boulevard regularly kill Portlanders. And make no mistake, Oregon has a serious and growing road safety problem: traffic deaths in Oregon increased 58 percent from 2013 to 2016–four times faster than nationally. The decision to plow $500 million into a project whose official purpose is described as “reducing minor and non-injury crashes” shows that when it comes to allocating resources, ODOT puts no weight on achieving vision zero. Instead, ODOT’s internal Public Involvement Plan shows just how cynically it has chosen to make “#1 crash location” a “key message” as part of thinly veiled marketing campaign.

3. How freeway expansion destroyed a neighborhood–and may again. In the 1950s and 1960s, the initial construction of the Interstate Highway System slashed through city neighborhoods around the nation. In Portland, Interstate 5 was routed through North and Northeast Portland, location of the city’s African-American neighborhoods. Freeway construction directly destroyed hundreds of homes, but more importantly destabilized neighborhoods that then experienced successive decades of economic and population decline. That was true in Portland’s Albina neighborhood, where population fell almost two-thirds in the decades after the freeway was completed. Nationally, economic studies suggest each additional radial freeway constructed through a city reduced its population 18 percent. In recent years, the Albina neighborhood has begun to recover; and just as it has, the Oregon Department of Transportation is proposing a freeway widening project that will bring more and faster traffic to city streets–something that’s especially ironic because a majority of neighborhood residents travel to work by walking, transit or by bike. The lesson of the twentieth century is that freeways and freeway generated traffic are inimical to healthy urban neighborhoods. Will we have to learn that lesson, again, the hard way, in the twenty-first?

4. Safety last: What we’ve learned from previous freeway “improvement” projects. We have a guest post from Naomi Fast, critically examining whether freeway capacity expansions actually do anything to improve safety. The proposed Rose Quarter freeway widening isn’t the first time that the Oregon Department of Transportation has invested in capacity improvements with the ostensible purpose of improving safety. A few years ago, it spent more than $70 million on capacity expansion at the I-5 Woodburn interchange, south of Portland. They pitched the project as a promoting safety by moving cars more efficiently on and off the freeway. There doesn’t seem to be any evidence that the project has worked: there were two serious injury accidents at the interchange in February, and ODOT’s own crash data show that the crash rate in this section of the freeway is, if anything, higher than before the project was undertaken.

In the News

1. The Portland Tribune published Joe Cortright’s commentary on the traffic effects of the Rose Quarter freeway: as has been demonstrated time and again, widening urban freeways only generates more driving, congestion and air pollution.

2. The Portland Business Journal (gated) published Joe Cortright’s Op-Ed estimating the extent of sales tax evasion in Vancouver Washington, and its impacts on traffic congestion in the Portland metropolitan area.