What City Observatory did this week

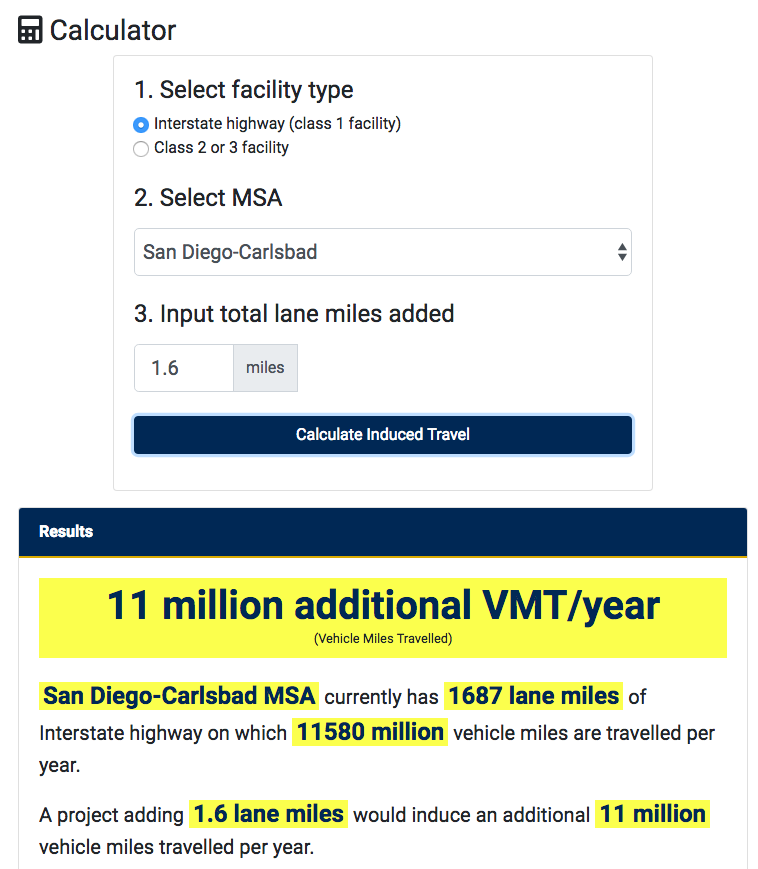

1. Widening freeways increases car travel and carbon emissions. Induced demand from additional freeway capacity is now so well proven that it’s referred to “The Fundamental Law of Road Congestion.” Based on the scientific literature showing how more road capacity produces more driving, the University of California Davis has built an on-line calculator to show how much more driving one can expect from any additional capacity. We use this calculator to develop estimates of how much more driving Portland can expect if it widens Interstate 5 at the Rose Quarter. The calculator’s answer: a wider freeway would generate 10 to 17 million more miles of vehicle travel each year, which would produce hundreds of thousands tons of additional carbon emissions.

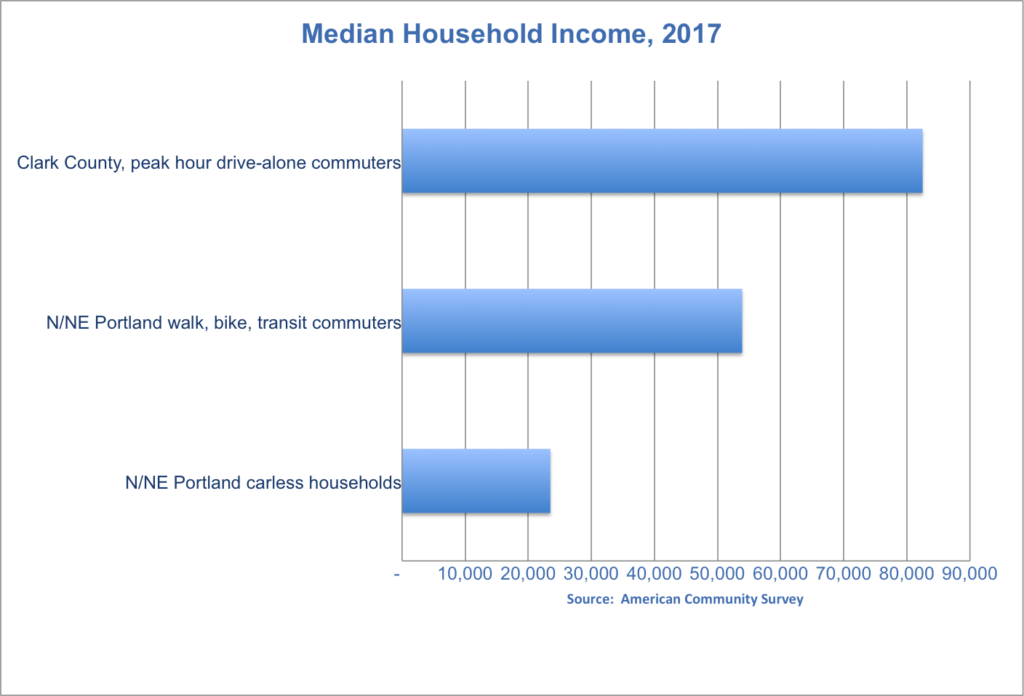

2. Deep demographic disparities between those who drive on freeways and those who live near them. Widening freeways systematically privileges higher income people. The median income of peak hour drive alone commuters from Washington state to jobs in Oregon is more than $82,000 per year, about 50 percent more than area residents who walk, take transit, or bike to work, and more than three times higher than the average household that doesn’t own a car. Similarly, while three-fourths of the peak-hour, drive alone commuters from Washington are white, non-Hispanic, more than two-thirds of the students attending the public school next to the freeway they’re driving on are persons of color, and half the students qualify for free and reduced price meals. Is there any transportation investment that’s more skewed against low income households and persons of color than widening inner-city freeways?

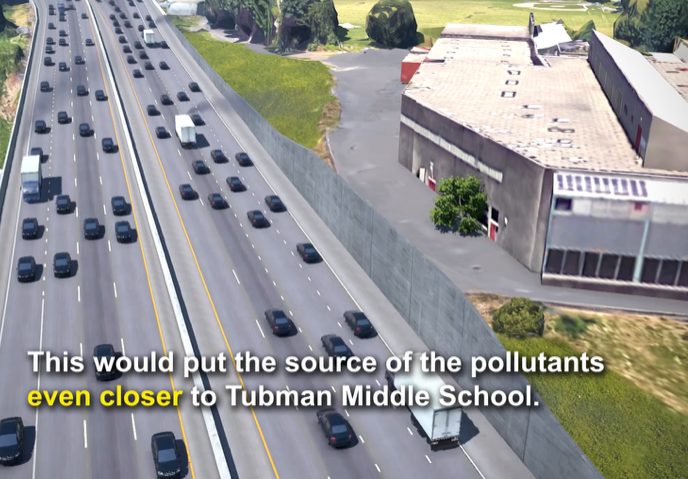

3. Why do poor school children have to pay to clean the air polluted by rich commuters? Portland Public Schools just spent over $12 million to install special state-of-the-art air filters at Tubman School, to clean up the air pollution from cars traveling on the stretch of I-5 that runs right by the school. It’s exactly the place that the Oregon Department of Transportation plans to widen the freeway, moving it even closer to the school. There’s a basic law and economics question here: Why does the school district have to pay for these filters–out of money that could otherwise be used for these kids education–rather than the Oregon DOT, and through them, the driver’s benefitting from the freeway. It’s not fair, and it’s also not efficient.

Must read

1. Looks like there’s a deal for congestion pricing in New York. After long expressing doubts about congestion pricing, New York Mayor Bill de Blasio has apparently agreed to support congestion pricing for New York City. The continuing financial crunch for the city’s transit system probably has a lot to do with his conversion. It’s estimated that congestion pricing could generate billions for transit construction and operations. But, the real payback, as Charles Komanoff has demonstrated, is that congestion pricing will likely dramatically reduce congestion on city streets, and improve the flow of traffic, especially transit buses, improving their service and cost efficiency, and likely taking pressure off the city’s overtaxed subway system. So, Bill: Come for the revenue, stay for the improved traffic flow. A successful roll out of pricing in Manhattan could be just the demonstration US cities need to apply this proven approach to urban congestion around the country.

2. LA and Portland push forward with congestion pricing studies. It looks like 2019 will be the year that congestion pricing gets traction in other cities as well. In Los Angeles, Metro has initiated a multi-year study. LA Councilman Paul Krekorian has a very succinct summary of the case for pricing in the Long Beach Post

A hugely disproportionate number of the people who use our system are transit-dependent, and they are disproportionately impacted by congestion slowing down buses,. We build really expensive streets that people use for free, and that is nothing but a subsidy to the automobile industry and people who use cars.

Meanwhile in Portland, where the state Legislature has already directed the Oregon Department of Transportation to pursue pricing on Interstate freeways, and where the Portland City Council has endorsed pricing as a transportation policy, Metro, the elected regional government is also pushing forward. Newly elected Metro President Lynn Peterson says she supports the state’s plans to toll I-5 and I-84, and wants to go further to explore how congestion pricing could alleviate congestion, and help the region meet other goals, like greenhouse gas reduction.

3. Jennie Schuetz on Oregon’s rent cap law. There were congratulations all around last week as the Oregon Legislature passed, and Governor Kate Brown signed a law capping annual rent increases for most Oregon tenants at inflation plus 7 percent. Much of the press coverage has a surprising degree of triumphalism, “a first in the nation statewide rent control program,” but for the most part the limits it imposes are pretty modest. In reality, it’s an “anti-rent-gouging” law, rather than rent control. Even so, Brookings Economist Jenny Schuetz has a few words of caution for the celebrants. Any form of rent control is likely to prompt some land owners to consider condominium conversion. In addition some aspects of the law incentivize perverse behavior: As written the law doesn’t cap rents on apartments newer than 15 years old; the presence of the cap may prompt landlords of units reaching that age to boost rents preemptively before the law applies to them. In addition, as Schuetz points out, the real trick in holding down rents is encouraging more supply. Other bills now pending in the Oregon Legislature to allow three- and four-plex homes in many single family zones, and to generally allow apartments in transit served locations in large cities, could really help address affordability in a more durable and effective fashion.

New Knowledge

Does broadband Internet corrode social capital? If we’re spending more time on Facebook, do we spend less time face-to-face? A new study from the UK looks at variations in broadband availability and detailed measures of social interaction. The research exploits a key bit of random variation in the initial deployment of broadband Internet. With DSL technology, the speed and availability of broadband were determined by proximity to a local switch, with more distant homes having much slower service. The authors of this study looked at measures of social capital, including personal interactions and civic engagement, and found that places with higher broadband speeds had lower rates of interaction and engagement. The findings are complicated: while people don’t seem to reduce their social interactions with friends, other activities do suffer: fast Internet crowded out forms of cultural consumption such as watching movies and attending concerts and theatre shows. In addition, broadband penetration significantly displaced civic engagement and political participation. The data also show that broadband adoption, and the amount of time spent on-line was positively associated with Internet speeds.

Geraci, A., Nardotto, M., Reggiani, T.,Sabatini, F. 2018. Broadband Internet and Social Capital. MUNI ECON Working Paper n. 2018-01. Brno: Masaryk University.

In the News

The Portland Mercury quoted our analysis of the likely increase in greenhouse gas emissions as a result of freeway widening in a story entitled, “I-5 Rose Quarter Expansion Could Increase Greenhouse Gas Emissions, Researchers Find”

Willamette Week summarized our analysis of the wide income disparities between the persons who will benefit from the Rose Quarter freeway widening project and those who will bear the impacts of the project’s increased traffic and pollution.