What City Observatory did this week

About those swelling suburbs. Much was made last week of a Wall Street Journal story noting that 14 of the 15 fastest growing cities with populations greater than 50,000 were suburbs. As with previous such reports, that’s been taken to mean that America’s urban revival is waning and that like previous generations, Millennials are revealing their true love of suburban living. We take issue with those claims, noting that well-educated young adults are still concentrating in cities more than previous generations, and that somewhat slower city growth in recent years, especially coupled as it is with high and rising rents, is a sign that we’re bumping up against the limits of housing supply in cities, not that demand for urban living has waned.

Must read

1. How the law made driving mandatory, and everything else illegal. A few months back, Greg Shill wrote an epic law review article detailing the ways in which the legal system has been systematically tilted to privilege car travel and discourage or make illegal other forms of transportation, particularly walking and biking. He’s back with a taut article at The Atlantic summarizing his analysis: “Americans shouldn’t have to drive, by the law insists on it.” From changes to who has the right of way on roads, to the tort law standards applied to drivers, to the way speed limits are set, to the allocation of funds to the tax system, we’ve written our laws to favor car travel. Little wonder we’ve become so dependent. The net effect, as Shill argues is:

Instead of merely accommodating some people’s desire to drive, our laws essentially force it on all of us—by subsidizing it, by punishing people who don’t do it, by building a physical landscape that requires it.”

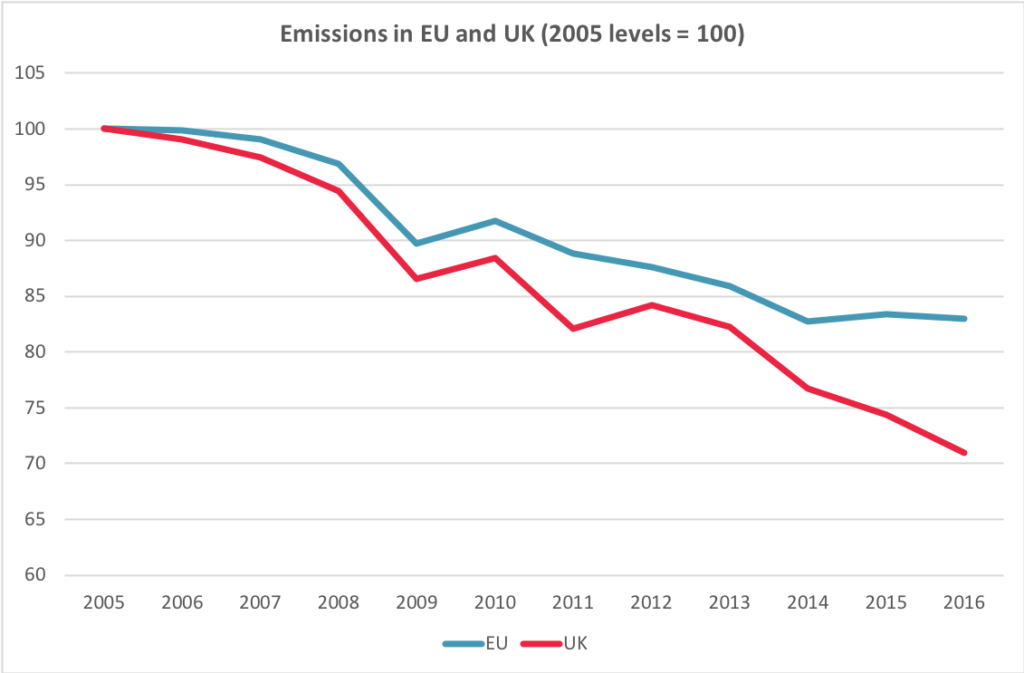

2. Carbon pricing works. Although proposals for cap and trade or cap and invest, and other indirect forms of carbon pricing are moving forward slowly in the US, there’s growing international evidence that carbon pricing, even at relatively modest levels, shifts consumption and investment decisions in ways that produce reductions in carbon emissions. Today’s case-in-point: the UK carbon price floor. Put in place in 2013 as a fix for a poorly designed trading system, the UK charges utilities the equivalent of about $25 for each ton of carbon emitted. According to a new report from Canada’s EcoFiscal Commission, the fee as helped produce a dramatic decline in carbon emissions, which have fallen more rapidly in the UK than in the rest of Europe.

At the margin, adding a price to carbon systematically encourages people and businesses to make lower carbon investment and consumption choices, and raises the financial returns from new low carbon technologies. If we’re going to seriously tackle the climate crisis, getting prices right will be a powerful impetus for collective action.

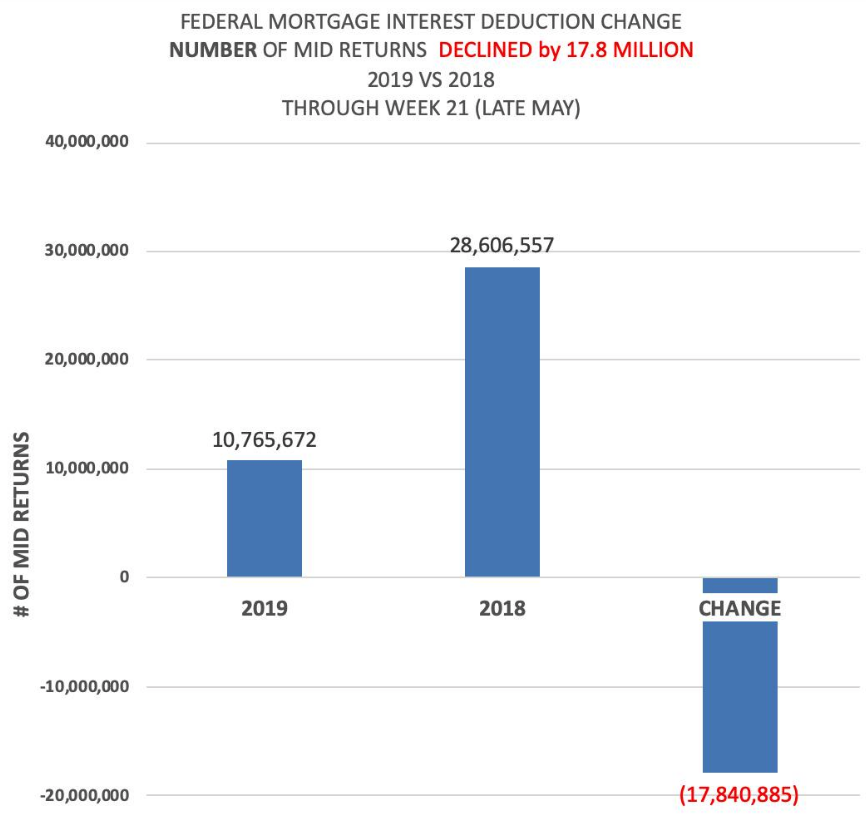

3. The amazing disappearing home mortgage interest deduction. One of the biggest changes included in the 2017 tax reform bill passed by Congress was the effective elimination of the mortgage interest deduction for most moderate income families. Increasing the standard deduction, to $24,000 for married couples, dramatically reduced the number of households who can itemize deductions and take advantage of the mortgage interest deduction. The change took effect in 2018, which means that tax returns filed in 2019 are the first to show the effects of the new provision. Tom Cusack of the Oregon Housing Blog notes that IRS data for returns filed through May show that the number of households claiming the mortgage interest deduction has fallen by more than 60 percent (more than 17 million fewer than in the previous year), and the volume of mortgage interest deducted has fallen by about $128 billion.

It’s striking that this is one of the biggest changes in federal housing policy in decades. It will be interesting to see how the loss of this key tax break influences home ownership in the years ahead. The remaining beneficiaries of the deduction tend to be even higher income households. (Hat tip to Tom Cusack of the Oregon Housing blog).

New Knowledge

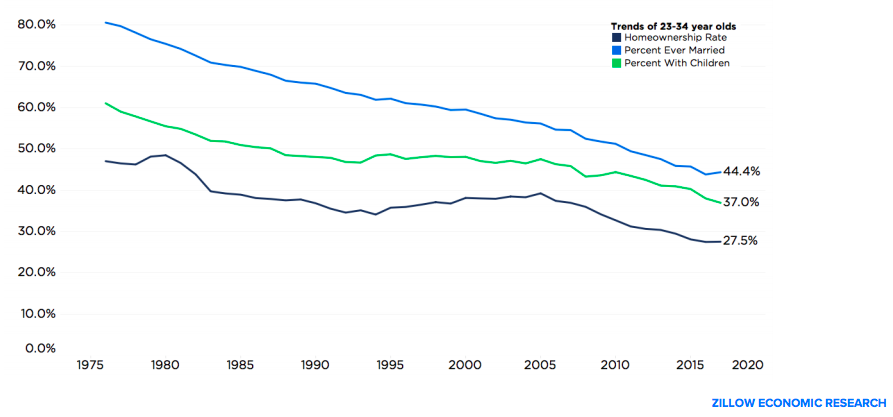

Yes, today’s young adults are behaving differently than those in previous generations. At City Observatory, we’ve long noted that today’s young adults, especially the group we call the Young and Restless (college-educated 25 to 34 year olds) are doing things differently than previous generations. We’ve chronicled their increasing tendency to choose to live in close-in urban neighborhoods. Economist Jeff Tucker at Zillow has pulled together some terrific data on other key behaviors of young adults over the past several decades. This chart shows the difference in rates of marriage, child-bearing and homeownership for 23 to 34 year olds.

The data show a steady–and persistent–decline in all these behaviors. In 1975, nearly four-in-five young adults had already been married; today it’s less than half. Three-in-five had kids in 1975; today its 37 percent. And while nearly half were homeowners in 1975, it’s less than 28 percent today. Despite the frequent contrarian stories you hear, none of these trends has reversed, or even weakened, in recent years.

That’s not to say that many, even most, of these young adults won’t eventually marry, have kids and buy houses. But they’ll do it much later in life, and cumulatively the effect of that delay profoundly changes the shape of demand for housing, and as we’ve frequently said, adds to our shortage of cities.

This chart is drawn from Jeff Tucker’s June 2019 presentation to the King County Assessor’ Office.

In the News

Slate’s Henry Grabar quotes City Observatory’s analysis of US and European pedestrian death rates in his article “Don’t count on US regulators to make self-driving cars safe for pedestrians.”