What City Observatory did this week

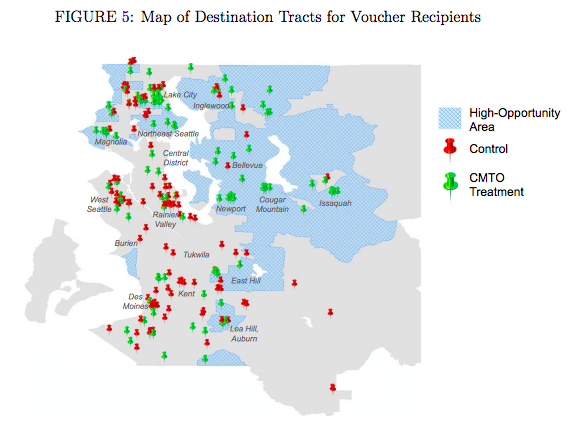

How helping families move to better neighborhoods reduces segregation and promotes opportunity. The work of the Opportunity Insights project, led by Harvard’s Raj Chetty, has shown convincingly that where you grow up has a profound influence on your life’s path. Kids from low income families that grow up in mixed income neighborhoods tend to have higher incomes (and are less frequently incarcerated) than otherwise similar kids who grow up in neighborhoods of concentrated poverty. A new demonstration program in Seattle has used housing vouchers, coupled with intensive support services for prospective tenants (and landlords) to see whether low income households will, given the chance, choose higher opportunity neighborhoods. The findings show that modest support services increase the number of families moving to high opportunity neighborhoods by 40 percentage points, compared to a control group of families offered housing vouchers, but no support.

The demonstration project also shows that families moving to high opportunity neighborhoods are much more satisfied with their new housing and neighborhoods than the control group. Based on the Opportunity Insights research, kids growing up in these neighborhoods can be expected to have considerably higher incomes as adults. In addition, the study also points out that we shouldn’t assume that low income households are highly attached to low opportunity neighborhoods–given somewhat better information, and some supporting services, many are happy to move to new neighborhoods that give their kids a chance for a better life.

Must read

1. Vehicle miles traveled by Uber and Lyft. The exact contribution of ride-hailing services like Uber and Lyft to urban traffic congestion has been a murky topic: the companies have been reluctant to share the copious data they’ve compiled about where and how much their ride-hailed vehicles traveled. That appears to be changing, a little. According to CityLab, the firms jointly engaged transportation planners Fehr and Peers to compile data on ride-hailed trips for a number of cities. These show that while ride-hailing makes up about 1-3 percent of metro level travel, the figure is much higher (7-12 percent in core counties of large metro areas like Boston, Seattle and Washington.

The real issue is in urban centers, where ride-hailed rides are disproportionately concentrated. As we’ve noted before at City Observatory, ride-hailing demand is closely associated with drinking, flying, and paying for parking. The cost of parking is a brake on driving to center cities, but Uber and Lyft avoid parking charges, and thereby drive additional travel in city centers.

The geographic concentration of Uber and Lyft traffic is clear evidence of the effect of pricing (and subsidies) on car use. Ride-hailing overcomes one cost of car use (parking charges) and has a significant subsidy (the billions of dollars Uber and Lyft shareholders are paying to cover money-losing service). The policy lesson here has less to do with ride-hailing, and much more to do with road pricing: If we price scarce and valuable city streets effectively, we’ll get less car traffic and less congestion. The Uber/Lyft business model (paying a la care for car travel, with rates varying by location and time of day is the core o the solution to urban traffic congestion.

2. Gentrification data: Hard-headed and hard-hearted? Writing at Greater Greater Washington, Alex Baca and Nick Finio reflect on the recent Philadelphia Federal Reserve study on gentrification. The heavily quantitative study (which we profiled at City Observatory) makes the strongest case yet that gentrification is rare, and seldom results in displacement of long-term residents. As Baca argues, while the numbers are indisputable, the underlying power imbalance between “the movers and the shaken,” the long history of urban change working to the disadvantage of the poor and people of color, and the often difficult to define sense of loss of neighborhood identity mean that the numbers alone don’t tell the whole story. Most concretely, the symbolism of gentrification–the construction of new housing–is simultaneously emblematic of an influx of capital, and also the best hope of minimizing displacement.

By the transitive property of signifiers of neighborhood change, the very new buildings that could possibly mitigate some negative effects of newcomers, by literally absorbing them without much displacement, are almost universally regarded as symbolizing the physical and cultural exclusion of current residents. Data can nearly never account for that.

3. Autonomous Vehicles start testing in New York. The New York Times provides a peak at a trial run of autonomous vehicles in the Brooklyn Navy Yard, by Optimus, an AV startup. Optimus has low speed electric shuttles traveling a loop around the yard providing free rides to workers and visitors in a relatively controlled environment. As in other places, the vehicles are staffed by human attendants monitoring their performance, and occasionally stepping in when the vehicles AI seems baffled. Brooklynites interviewed about the vehicles seemed skeptical of their utility. As the article reports:

Matt Cortright, an architectural designer who rides his bike to work (the cars have a bike rack), said that a driverless car is still a car. “My general perception is we have too many cars already and adding cars without drivers doesn’t solve the problem.” he said.

Plus, he added, “If I get hit by a car, I want to be able to sue the person driving it.”

New knowledge

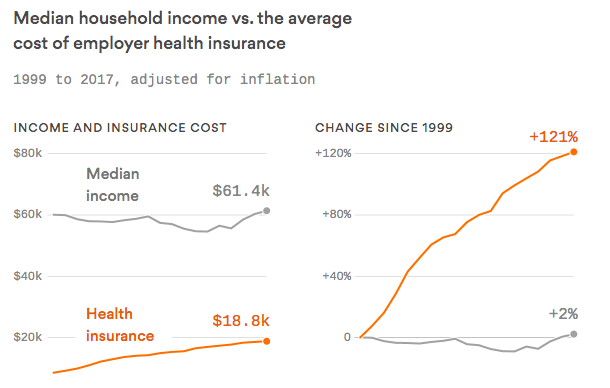

How health care ate our take home pay. Axios has a succinct chart showing how much of our change in compensation over the past several decades has gone to health care costs. The average household’s income, in real, inflation-adjusted terms has barely budged–up 2 percent–since 1999. But health care costs have gone up 121 percent (again, inflation-adjusted). Health care works out to the equivalent of roughly 30 percent of median household income, about $18,800 per year out of a total income of $61,400 per year.

In the news

City Observatory’s Joe Cortright is quoted in a Bloomberg Business story exploring the challenges of tapping the asset value of public land to tackle affordable housing in Seattle.