What City Observatory did this week

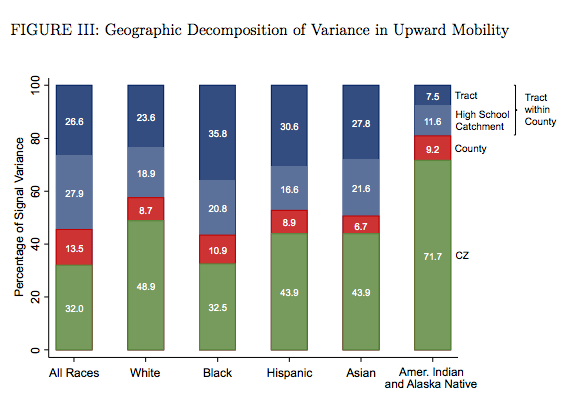

1. The neighborhood you grow up shapes your life chances, especially for black kids. New research from the Equality of Opportunity Project shows the profound effect that neighborhoods have on lifetime economic results. Raj Chetty, Nate Hendren and their colleagues have calculated how much of the effect of place plays out at the regional (metropolitan or county level, compared to the very local level: the school attendance area or neighborhood. It turns out that for black kids, these very local effects are even stronger than for everyone else. Whereas local neighborhood effects account for a little more than 40 percent of the place-based effects on white children’s outcomes, they account for about 57 percent of the place based effects on black children.

2. Housing can’t both be a great investment and be affordable. There’s a deep contradiction that underlies housing policy in the US. We firmly believe two incompatible things: housing should be a great investment for the typical family and housing should be affordable. It turns out, though, that the only way housing is a great investment is that it increases in value faster than inflation, or incomes or alternative investments. And by definition, rising home prices that count as one group’s return on investment, turn out to be an affordability burden for everyone else.

3. Get out! Why it may be necessary for some people to leave the place they grew up in order to realize their fullest economic opportunities. We’ve been taking a close look at the Opportunity Atlas, a stunning new high definition picture of how the place you grew up correlates with your lifetime earnings. One feature of the Atlas is a map showing what fraction of kids who grew up in a place still lived their as adults. There’s a striking contrast between the Great Plains (which generally have high levels of economic mobility) and much of Appalachia (which have lower levels of intergenerational economic mobility). These differences are also reflected in migration rates: kids in the Great Plains are much more likely to move away as adults. We think this willingness and ability to move may be one reason they do better economically as adults.

Must read

1. Revitalization without gentrification. Strongtowns has a fascinating interview with Dallas-based developer Derek Avery, who specializes in building mixed income housing in black neighborhoods. Avery tackles the issue of gentrification head-on, and has a three-pronged strategy for making sure his projects fit in with, and are widely seen as improving the neighborhood. According to Avery, the three keys are

- They build market rate and more affordable (smaller) housing.

- They make a point of talking with neighbors early on.

- They engage with local schools.

Avery’s strategy stresses building a long term commitment, aimed at creating a stronger, mixed income community that has a place both for current residents and newcomers. He explains:

One of the things we settled in on is that to affect education and the social changes that we want, we have to approach it from the base level of how we design neighborhoods.

Typically we do projects in those high crime areas, close to the central business district. They are majority black neighborhoods. We said what we really wanted to do was activate the community and involve them in the revitalization. Because it’s easy to build houses. Everyone told me I was crazy for going there and building houses that were a little more expensive. They said I would be told I’m gentrifying, but the only thing that works is mixed income. That’s been proven time and time again. You can’t have concentrated poverty, but you can’t displace everyone. You have to preserve what’s there, but also bring in things in a controlled manner to inspire reinvestment.

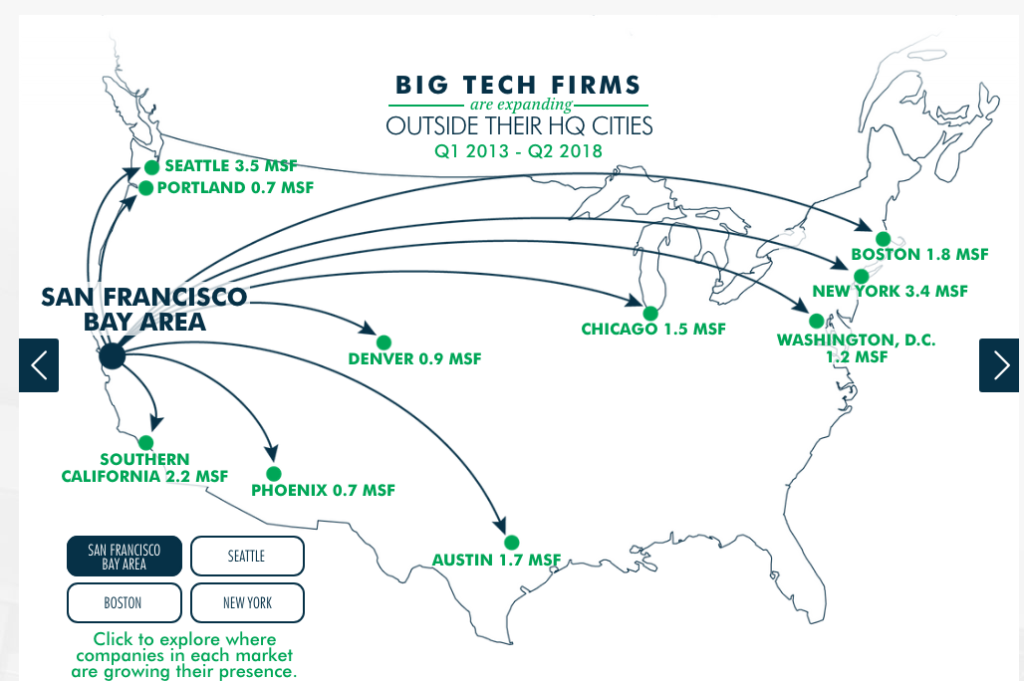

2. Tech firms expanding outside the Bay Area. Real estate firm CBRE has put together a series of compelling maps showing where various tech firms are leasing new office space away from their home base locations. The biggest demand is coming from firms headquartered in the famously expensive (and housing constrained) San Francisco/San Jose Bay Area. Bay area headquartered tech firms are leasing millions of square feet in cities around the nation. And before you economic development types start salivating too much, notice where they’re headed: largely to other major tech centers around the nation. Seattle and New York top the list of destinations for big tech firms, confirming that while they’re looking beyond Silicon Valley, they’re most likely to choose locations that already have a strong technology workforce base.

3. Fast, Furious and Fatal, the 85 percentile rule. We’ve been critical of many of the crazy rules of thumb that are routinely used by transportation planners, but which enshrine unsafe and unscientific ideas. One of the most pernicious examples of this kind of foolishness is the very mathy sounding “85th percentile” rule, that says speed limits on roadways should be set no lower than will cause more than 15 percent of observed road users to be violating the law. So if 20 percent of the current users of a roadway are travelling at 45 miles per hour, the speed limit can’t be any lower than that level. California law which mandates use of the 85 percent rule actually required the city of Los Angeles to raise posted speed limits on many streets, when that would demonstrably make roads more dangerous. This insanity is explained in a recent brief from the State Smart Transportation Initiative, called “Fast, Furious and Fatal.”

4. The MicroTransit Mirage. Jarrett Walker, one of the nation’s leading transit planning consultants, has a compelling essay on the limits of microtransit. Tech firms and some vendors are peddling a vision of transit in which multi-passenger vehicles provide dispatched, door-to-door service; instead of walking to a bus stop, you’ll get picked up an your home and dropped at your destination. While there’s a flashy new technological veneer for this idea, it is essentially the same as the existing dial-a-ride services that operate around the country. The limiting factor is one of economics, driven by the fact that such services typically manage only about four boarding rides per hour of service. That’s neither cost-competitive with bus transit, nor does it scale to provide service in dense urban environments. As Walker argues, you can’t beat the bus.

New Knowledge

More evidence that walkability is associated with higher values. A new study from Jeremy Gabe (University of Auckland), Spenser Robinson (Central Michigan University) and Drew Sanderford (University of Arizona), looks at the connection between various aspects of the built environment and the rental prices of multi-family apartments around the country. Their model includes an estimate of the contribution of the EPA walkability index, and finds a positive and statistically significant relationship between apartment rents and walkability (people pay more to be in a walkable location.

The author’s qualify their finding by reporting that a slightly different specification of their model that includes a longer list of variables causes the walkability index to lose its statistical significance. We think that may have something to do with the fact that the variables that this larger model incorporates includes several components that are also part of the EPA walkability index (including, for example intersection density and mix of building types). It shouldn’t be surprising that once one controls for these features directly that the EPA index is no longer significant. (We also question why the authors chose to use the EPA index, which is calculated based on just four variables at the block group level, rather than using Redfin’s WalksScore, which is available for individual addresses, and computes walkability based on the proximity of ten different categories of destinations. Despite these reservations, this work adds to a growing body of data showing that the features of the urban environment that support walkability are positively correlated with consumer’s willingness to pay.

Jeremy Gabe & Spenser Robinson & Andrew Sanderford, 2018. “Urban Sustainability Preferences Revealed Through Multifamily Rents,” ERES eres2018_103, European Real Estate Society (ERES).

In the News

Tampa’s ABC News cited our skepticism about a recent study claiming ride-hailing was responsible for an increase in car crashes.