What City Observatory did this week

1. Cities as selection environments. It’s an article of faith in the economic development business that cheaper is better, or at least more competitive. The claim is that businesses will always gravitate toward and flourish in places with cheap rents, low wages, favorable taxation and generous subsidies. That’s always been debatable, but there’s more: as the old saying goes “Anything that doesn’t kill you makes you stronger.” So it is with what Michael Porter has called “selective factor disadvantages.” Sometimes it’s the case that being more expensive (or having limited resources) forces businesses to be innovate or become more productive to compensate. A lack of coal, for example, prompted Italian steelmakers to invent a highly efficient process for making steel from scrap in electric-fired mini-mills. That’s not to rationalize every cost, but it should counsel cities to recognize that some aspects of the local environment that seem less than hospitable may actually provide a strategic benefit.

2. Has Fruitvale figured out how to prevent gentrification and displacement? A few weeks back, a study caught our eye with the startling claim that “transit oriented development can prevent displacement.” The story was based on a recent UCLA study looking at demographic change in Oakland’s Fruitvale neighborhood. We took a closer look. The study notes that Fruitvale’s population remained majority Latino, while another Oakland neighborhood of color, Uptown, saw a decline in its African-American population and an increase in the white, non-Hispanic population. Does this mean Fruitvale avoided gentrification? Upon closer inspection, we don’t think so. While census data can tell us the overall demographics of the population, it doesn’t reflect whether residents from 2000 still live in the neighborhood. It’s also apparent that the economic forces behind neighborhood change are regional: home prices rose by almost exactly the same amount in “non-gentrifying” Fruitvale as in “gentrifying” Uptown, so in neither place were residents spared big rent increases. One key difference though: Fruitvale added significantly to its housing stock and population, while Uptown built only a handful of new homes and saw its population decline. Our takeaway: if you want to minimize displacement, build more housing.

3. Why have we made it illegal to build the kind of neighborhoods Americans most love? We reprise one of our most insightful commentaries from our friend Robert Liberty. He describes living in Northwest Portland, an old urbanist neighborhood with narrow streets, a mix of larger single family homes, duplexes and four-plexes, apartment courts and apartment blocks, as well as a neighborhoods shops and even some light industrial uses, all in a walkable gridded area. It’s one of Portland’s best loved and highest value neighborhoods, but it would be illegal to build today: in most places the streets have to be wider, residential uses have to be separated from commercial and industrial ones, and you can’t mix single family homes with apartments. Maybe it’s time to reconsider whether our land use laws are aligned with the kinds of urban environments we most value and enjoy.

Must read

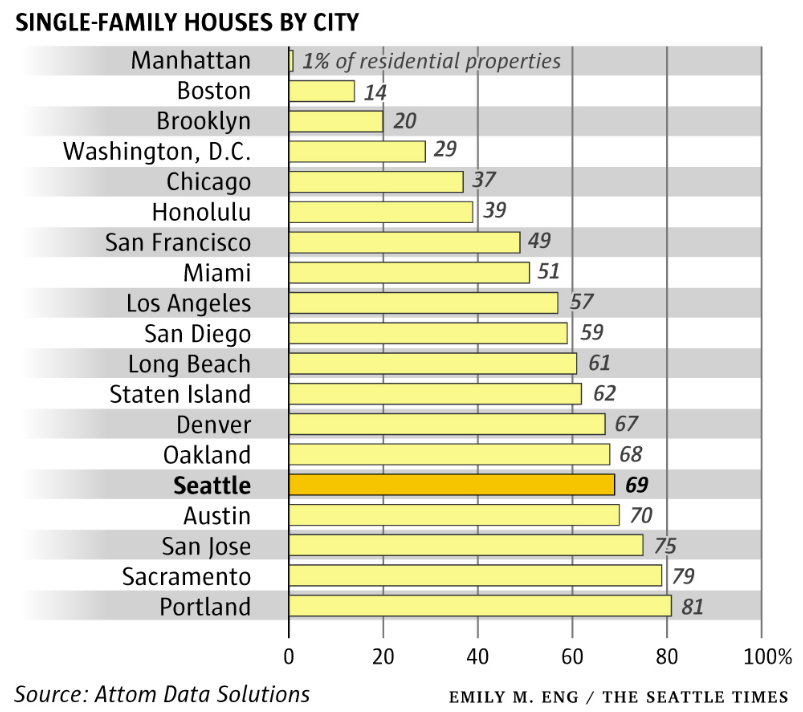

1. How sweeping is your city’s apartment ban? Like most American cities, the vast majority of Seattle is zoned exclusively for single family structures. While the city is in the midst of a historic building boom, nearly all of the new construction is happening in the relatively few places it’s permissible to build multi-story apartments. Vast swaths of the city are effectively off limits to new development, with the result that housing supply is pinched, and prices (and rents) continue to rise. The Seattle Times’ Mike Rosenberg has an graphic analysis of Seattle’s single family zoning, and also estimates of the share of properties that are single family in major cities (this doesn’t appear to be the share of land, or necessarily what’s allowed under zoning; but it does emphasize the predominance of single family homes in most cities.

2. Don’t obsess about green building; focus on green zoning. The always incisive Lloyd Alter has an excellent analysis of the environmental importance of achieving greater density. While we tend to fetishize building technology through flashy new technologies and LEED certification, what does the heavy lifting in energy conservation and greenhouse gas reduction is simply building more densely. There’s a strong correlation between greater residential densities and lower building and transportation emissions. Build as many LEED certified buildings as you like, if they’re built at low density, transportation emissions will overwhelm their ostensible energy and pollution savings.

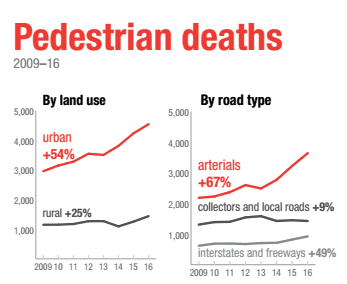

3. Pedestrian deaths hit a 28-year high. A new report from the Insurance Institute for Highway Safety highlights a grim statistic: more than 6,000 pedestrians were killed on the nation’s streets in the past year, the highest number since 1990. The study highlights the growing number of Sport Utility Vehicles, and the particular danger of multi-lane arterials, where traffic speeds are lethal to pedestrians. Pedestrian deaths are up 46 percent since 2009, and although the report doesn’t mention it, that date corresponds to a trough in vehicle miles driven. Since 2014, declining gas prices have fueled additional driving, and a growing number of crashes. And pedestrians are bearing much of the cost.

In the news

1. CityLab republished our analysis of the failure of SB 827 “Will there be no exit from California’s housing hell?”

2. So did Strong Towns: “No Exit from Housing Hell.”