You might not think it, but New York City has a below-market affordable housing infrastructure that most other cities can only dream of. As one of the only major American cities not to tear down large amounts of its legacy public housing, it has nearly 180,000 units. Many more are in other below-market housing programs. And then, of course, there’s the city’s rent control and rent stabilization policies. In all, just 38.9 percent of New York City’s rental housing is entirely priced by the market.

But overwhelming demand—and the relatively slow pace of market-rate construction, at least up until recently—means that there’s still a massive housing shortage at almost every price range. The bidding war over scarce homes has led to situations like that of Chelsea, in Manhattan, where 29 percent of homes are in public housing or another income-restricted program, creating some space for low-income households—but market-rate units are so expensive that they price out all but the wealthy. And when below-market units do open up, the crush of applications makes affordable housing seem more like a lottery prize than a social safety net.

Under former mayor Michael Bloomberg, the city attempted to address the crisis in a number of ways. A series of rezonings created corridors in which developers could add more housing to address the shortage. But studies have shown that overall, downzones (reducing allowed density) actually outnumbered upzones (increasing allowed density) under the Bloomberg Administration. In those years, the city also created a “voluntary inclusionary housing” law, giving developers density bonuses in exchange for below-market units. But that program produced a relative handful of actual housing—just a few thousand units through the end of last year in a city of eight and a half million.

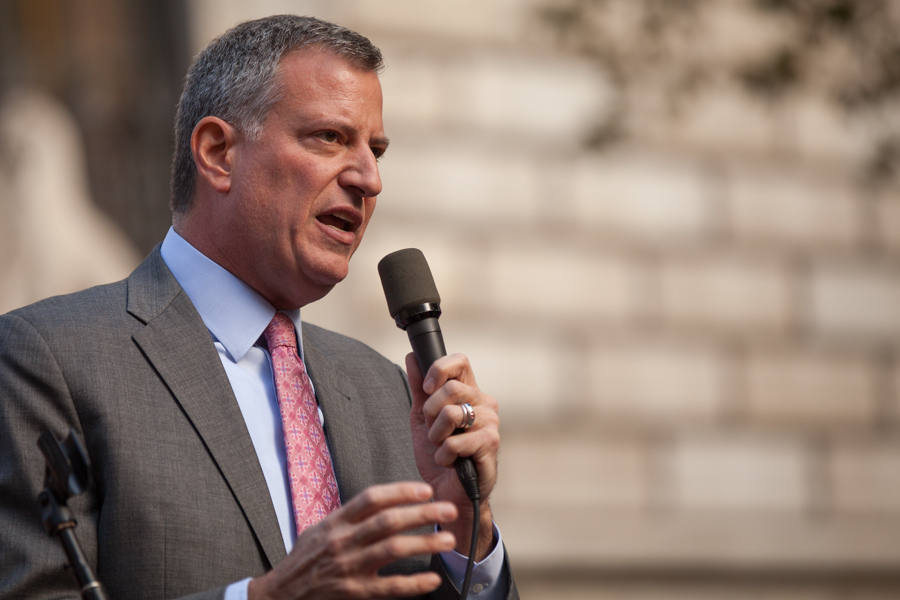

Current mayor Bill de Blasio was elected in 2013 on a platform of reducing the gap between New York’s rich and poor, including addressing spiraling housing costs. Soon after, his administration released an ambitious ten-year housing plan, which laid out a sprawling agenda to reform everything from zoning to finance to preservation, leading to the preservation of 120,000 below market rate units, the construction of 80,000 more, as well as the construction of thousands more market rate homes. Many of the plan’s key points were combined into two pieces of legislation: Mandatory Inclusionary Housing (MIH) and Zoning for Quality and Affordability (ZQA).

MIH aimed to remedy what many saw as a fatal flaw of Bloomberg’s voluntary inclusionary zoning scheme: namely, the voluntary part. It proposed that in all newly upzoned districts, developers would be required to set aside a certain proportion of their units at below-market rates. Exactly how many, and at what prices, would be determined by the City Council. MIH proposed a menu of three choices, ranging from 25-30 percent of units and 60-120 percent of area median income; the idea was that the Council would pick the level most appropriate for the neighborhood being upzoned.

ZQA included a raft of tweaks to the zoning code: harder to explain that MIH, but probably more consequential. Among the changes:

- Parking requirements near the subway would be dramatically reduced, allowing more buildable area to be used as housing for people, rather than being required to be set aside for storage of cars, and reducing the cost of development—a big deal particularly for affordable developers

- Increases of one to three stories in maximum building height for certain senior and low-income housing developments

- Adjustments to “contextual” zoning requirements and other regulations aimed at improving the built environment

When MIH and ZQA were released in early 2015, some applauded, but many came out in opposition. Preservationists opposed ZQA’s lifting of height limits by up to 15 feet in “contextual districts”; some affordability advocates argued that MIH’s affordability wasn’t deep enough, and, in some cases, that allowing more market-rate construction, even if tied to subsidized units, would necessarily further gentrification; and in other cases, objections included the time-honored fear of increased competition for “free” on-street parking as a result of ZQA’s parking requirement reductions.

These concerns and others led the vast majority of Community Boards—local advisory bodies to City Council members—to reject the proposals last fall. The votes were widely reported as a major setback for the mayor, though de Blasio remained defiant.

In fact, just a few months later, the City Council overwhelming approved both measures largely intact. Partly, this may reflect that political actors expected the Community Boards, whose local constituencies tend to reflect the same skepticism of development and change as other local bodies around the country, to be critical of any plans like MIH and ZQA. Also important is that de Blasio, whose approval rating climbed above 50 percent early this year, has a working majority aligned with him in the Council that may have been unwilling to torpedo one of his signature policy initiatives.

But his office also brought a strong array of interests to organize and testify in favor of the reforms in front of the City Council in February, even as other advocates argued that the plan didn’t go far enough. Groups urging passage included architects, business groups, the senior organization AARP, affordable housing developers, and several large labor unions, among others.

The Council did make a few tweaks to the initial proposals before passing them. Most notably, in response to concerns about the depth of affordability in MIH, it added a fourth menu option, with 20 percent of units at 40 percent of Area Median Income, and tweaked the third to drop average AMI to 115 percent, with portions required to be at 70 percent and 90 percent. Some of ZQA’s height bonuses were scaled back, and the “transit zones” of the city in which parking reductions would apply were also shrunk somewhat.

How much of an impact will these reforms have? It’s unclear. MIH, in particular, applies only to parcels that the City Council votes to upzone in the future. Several neighborhood rezonings are on the docket, but each presents a politically fraught vote that can be contested, although advocates hope that the menu of affordability options created by MIH will smooth the negotiations process. One of the first such up-zoning cases–a proposal to add 175 affordable housing units to a proposed apartment building in Manhattan’s Inwood neighborhood was shot down when a local City Councilor–who had voted for Di Blasio’s MIH plan–came out in opposition to the project.

Even if all of the upzones pass, however, most of the city will remain outside the requirements of MIH. Moreover, in some of these neighborhoods, such the low-income Brooklyn community of East New York, it’s not clear that large-scale market-rate construction projects that would trigger MIH requirements are yet financially viable. In addition, the expiration of a state program known as 421a (which provides a property tax exemption for affordable units) may threaten the effectiveness of MIH.

For these and other reasons—including issues that apply to inclusionary zoning strategies generally—MIH is not likely to create a large proportion of the affordable units in the de Blasio administration’s housing plan. In fact, last year, the city’s Association for Neighborhood and Housing Development, which supported the plan, estimated that the original version of the plan might produce 13,800 affordable units, out of the 80,000 new units, and 200,000 new and preserved, envisioned by the Housing New York plan over the next ten years.

ZQA, in contrast, does not require any future action by the Council. It may lead to thousands of new affordable units in several ways, including allowing affordable developers to build more units on parking lots that are no longer required; allowing affordable developers to build more densely; and making affordability incentives for market-rate developers more attractive by better aligning allowed building envelopes with floor area bonuses. Unlike MIH, however, there is no guarantee that the affordable units produced by ZQA will be part of mixed-income projects, or mixed-income neighborhoods, that encourage economic integration.

For observers outside New York, there are several lessons in all of this. Perhaps a major one is that there may be low-hanging fruit in zoning reforms, such as those passed in ZQA, that don’t get immediate recognition as affordability policies like inclusionary zoning does.

Another is that perhaps because of this difference in perception, ZQA-type zoning reforms may be easier to pass in a package with more traditional affordability policies like IZ. The decision to propose and vote on ZQA and MIH together, even though they were separate bills, appears to have been driven by exactly this political calculation.

For larger cities with neighborhoods in many different economic conditions, it will also be interesting to see whether New York’s approach—essentially passing an enabling law that creates a menu of inclusionary zoning requirements for future application—does indeed reduce bargaining costs for future upzonings.

But it’s also important to keep in mind that these represent just part of de Blasio’s larger housing plan. Getting to the headline numbers of 200,000 affordable units created or preserved will depend heavily on other parts of the plan—perhaps most notably a commitment to doubling capital funds for affordable housing, at over $8 billion over ten years. How many other cities have the political appetite, or financial ability, to create that level of funding, even adjusted for New York’s size?

Moreover, though de Blasio’s plan is among the most ambitious in the country, 80,000 new affordable homes, and 120,000 preserved, won’t solve New York’s housing crisis. Even the nation’s largest city is heavily dependent on policies outside of its direct control, from federal subsidies for programs like Housing Choice Vouchers and LIHTC, to state programs like 421a, to the zoning decisions of suburban municipalities who play a major role in the housing shortage that has pushed up market prices across the metropolitan area.

In some ways, New York City has set an example for other American cities by bringing together a coalition of affordability advocates, developers, and labor interests to support zoning changes to increase the supply of low-income and market-rate housing, as well as double the spending devoted to low-income housing. But it also demonstrates the limits of municipalities’ power to address housing issues. For reasons of both resources and coordination, the battle for fair, plentiful, and affordable housing has to be taken far beyond City Hall.