Portland’s Metro regional government would be committing planning malpractice and enabling lasting fiscal and environmental damage if it goes along with state highway department freeway widening plans

- The proposed $5 billion, 5-mile long, 12-lane freeway I-5 bridge project is being advanced based on outdated traffic projections using 2005 data.

- ODOT is pushing freeway plans piecemeal, with no acknowledgement that they are creating new bottlenecks.

- Freeway plans fail to address climate change and don’t acknowledge that new capacity will produce additional travel and increased greenhouse gases

- I-5 bridge plans are inconsistent with adopted state, regional and city commitments to use road pricing to manage demand, which would obviate the need for expensive capacity

- ODOT and WSDOT have not produced a viable financing plan for the project, which would be the region’s most expensive, and which has a $3.4 billion financial hole.

In theory, Portland has a smart approach to regional planning. It has a directly elected regional government, with strong planning authority over transportation and land use. That government claims to care deeply about the climate crisis, and regularly touts the sophistication of its transportation modeling team. And it says it’s looking at how the whole system works to make Portland a greener more just place.

But when it comes to the single largest transportation investment in the region, a proposed $5 billion 5-mile long, 12-lane wide freeway project across the Columbia River, it’s simply abdicating its responsibility and betraying its stated principles.

Next month, the Metro government is being asked to approve $36 million in additional funds for further planning of this massive freeway project. It should say no.

This approval is one more brick in the wall of an even larger freeway building plan. The Oregon Department of Transportation is pushing an entire series of freeway widening efforts, including the $1.2 billion Rose Quarter project, $5 billion for the mis-named “I5 Bridge Program” and billions more for widening I-205 and I-5 at the Boone Bridge in Wilsonville.

In theory, a regional planning agency would be guided by current, accurate data and scientifically based models. It would insist on knowing how each project fitted into a larger, long-term vision of how roads and transportation system would work. It would insist on knowing what a project will cost, how it will be paid for, and who will pay for it. And if it has committed itself to pricing roadways, it should know how pricing will affect demand before it commits billions on capacity that may not be needed or valued. And if it is serious about its oft-repeated commitments to tackling climate change, it should insist that its investments actually result in fewer vehicle miles traveled, and less greenhouse gases.

In practice, Portland Metro has done none of these essential things as it has considered the I-5 Bridge.

No forecasts. Most fundamentally and technocratically, ODOT has not prepared, and Metro has not reviewed or analyzed current traffic forecasts that show the actual and projected demand for the I-5 bridge. The foundation of any road project is estimates of the future level of traffic the roadway is expected to carry. Just last week, the staff working on the bridge project admitted that after more than two years of work to revive the failed CRC, they have no new traffic forecasts, and won’t have any for at least another year. That hasn’t stopped them from claiming that they know just how big the project should be (they say “ten lanes”) and from claiming that other alternatives won’t meet the project’s purpose and need. (As we’ve noted before, the two DOTs may claim it’s a “ten lane” project, but they’re planning on building a structure that would easily accomodate a dozen freeway lanes).

The last traffic projections prepared for the I-5 bridge as part of the project’s environmental impact statement date back more than a decade, and are based on data from 2005.

Ruling out alternatives and deciding on the size and design of a highway project before preparing and carefully vetting traffic forecasts is the opposite of planning.

No comprehensive look: building a badder bottleneck for billions. As noted earlier, the I-5 bridge project is just one of a series of Portland-area freeway widenings. Metro should be asking what the region, its environment, and its transportation system would look like with and without all these projects. Instead, it is considering them only piecemeal.

In effect, this approach amounts to approving the creation of new bottlenecks on the freeway system that will undoubtedly trigger efforts to widen freeways yet again in the future. The I-5 bridge project would widen I-5 from six to as many as twelve lanes from Vancouver to Victory Boulevard (the project claims its just ten lanes, but in the past it has lied about the actual physical width of the project it plans to build). ODOT is also planning to widen I-5 at the Rose Quarter to as many as ten lanes. Once these two I-5 projects are complete, a new bottleneck will be formed between them in the three-mile long six-lane wide section of I-5 between the Fremont Bridge and Victory Boulevard, with 12 lanes feeding into six at the north, and 14 lanes (I-5 plus I-405) feeding into this stretch of freeway from the south. ODOT will then no doubt call for the construction of further “auxiliary” lanes) to carry traffic between exits on this newly bottlenecked segment of I-5. In essence ODOT is building very large funnels at either end of this six-lane stretch of I-5 North, which will predictably lead to further traffic congestion, more pollution, and additional demands to waste billions of dollars widening roads to accommodate this traffic.

As Metro staff noted in their comments on the I-5 Rose Quarter project, the Oregon Department of Transportation routinely lies about the fact that it is expanding freeway capacity. It wrote of ODOT’s claim that it was not expanding I-5:

This statement is not objectively true and is potentially misleading; auxiliary lanes clearly add capacity.

Piecemeal reviews that approve segments on an ad hoc basis, and don’t consider the long-term effects of encouraging even more car traffic are the opposite of planning.

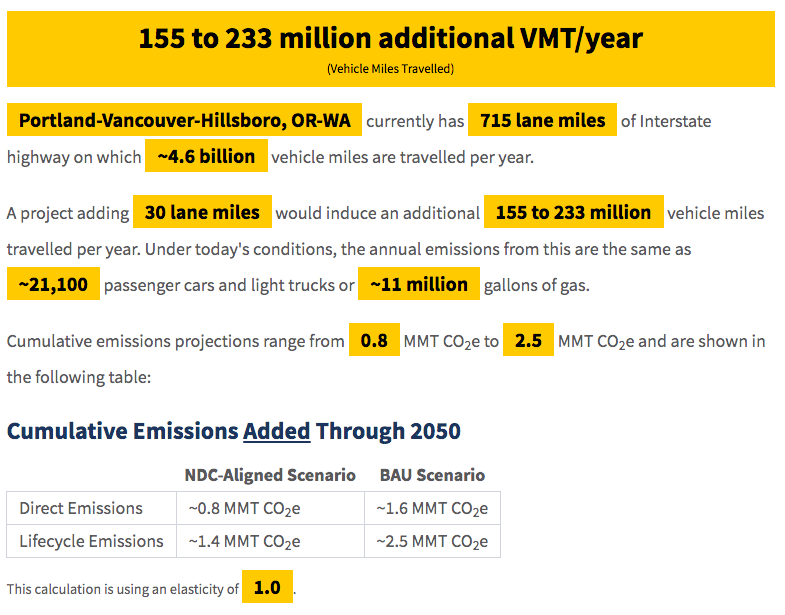

Not following through on fighting climate change. The original CRC was conceived with no notion of the seriousness of the climate challenge. The proponents of the new I5 bridge have steadfastly opposed incorporating climate considerations in the project’s purpose and need statement. It’s clear from their choice of alternatives (every one includes at least ten lanes of freeway), and claims that the inclusion of sidewalks, bike paths and transit as somehow make the project “climate friendly,” that nothing has changed with this new iterations of the project. Never mind that the authoritative Induced Travel calculator based on research from the University of California Davis, shows that expanding I-5 to 10 or 12 lanes for five miles would add 155 to 233 million miles of driving and 800,000 to 2.5 million tons of greenhouse gases. Freeway widening would worsen the climate crisis.

Of course, these calculations don’t include the effects of congestion pricing. Tolling I-5, which will be needed to pay for this project, would likely reduce and divert traffic (as we explain below), and ODOT’s own consultants show that tolling would reduce I-5 traffic by enough to entirely eliminate the need for widening I-5 at all. If the project manages somehow not to be tolled (as many in Clark County want) it would tend to produce vastly more traffic and pollution, as estimated by this calculator.

At $5 billion, the proposed I-5 bridge project is the largest single spending item in the Regional Transportation Plan. If Metro isn’t going to undertake a serious appraisal of the greenhouse gas impacts of building or not building this freeway then it doesn’t really have a climate strategy.

Metro is officially on record as supporting efforts to address climate change. Metro has said it wants to reduce greenhouse gases by 20 percent by 2035. But so far, its efforts have yielded no decline in emissions. And greenhouse gas emissions from transportation in metro Portland have actually increased by 1,000 pounds per person in the past five years. Metro has so far done nothing, and this and other freeway widening projects will make pollution worse.

At best, the I-5 bridge advocates pay lip service to climate issues, completely ignoring the effects of added road capacity on likely travel volumes and greenhouse gases, and instead making vague and unquantified claims that pedestrian and bike facilities on the bridge, plus transit improvements will somehow ameliorate the climate damage done by doubling freeway capacity.

Approving funding for a climate polluting freeway widening project, and failing to insist on developing a more climate friendly alternative way of spending $5 billion is the opposite of planning, and a betrayal of Metro’s stated climate commitments.

A failure to plan for road-pricing. The State Legislature, ODOT, the City of Portland and Metro have all said that road pricing will be a key component of the region’s future transportation system. Pricing can help better manage roadways, reduce peak hour traffic, lower the need for additional capacity, and provide funding for maintenance and equitable alternatives. Metro should not approve a $5 billion freeway project without a clear idea of how the project integrates with a system of road pricing—and yet ODOT and WSDOT have done essentially nothing to integrate these two concepts.

ODOT faces a profound dilemma with regard to road pricing. Its financial analysis counts on at least $1.4 billion in revenue from tolling the I-5 bridge. But the project is being sized and designed as if it needs to handle 180,000 vehicles per day, based on traffic projections—outdated, using 2005 data, and built using a model that ODOT concedes can’t address the effect of tolling.

But imposing tolls will profoundly reduce traffic growth. ODOT’s own consultants, in work completed after the CRC FEIS, have said that the proposed tolls on the I-5 bridges would reduce traffic levels on the bridge from their current level of approximately 130,000 trips per day to only 85,000. (And this is a firm that routinely over-estimates traffic on toll roads). Road pricing could dramatically reduce the need for expensive infrastructure. Yet ODOT has not incorporated the traffic-reducing effects of tolling into its design or alternatives analysis. They are treating it purely as a financial afterthought: a way to pay for a over-sized roadway after they’ve borrowed billions of dollars to build it. That’s exactly what Louisville did with a remarkably similar project (widening I-65 from 6 to 12 lanes across the Ohio River); there $1 tolls caused traffic to fall by almost half.

Louisville’s I-65 bridges at rush hour: $1 tolls eliminated tens of thousands of daily trips

If Metro were to demand that road pricing be implemented before squandering billions on this project, it would likely find that the region had more than adequate transportation capacity across the Columbia River. A region that says it is going to implement road pricing doesn’t commit to a multi-billion dollar freeway project based on outdated projections, and subsidize expensive freeway capacity that won’t be needed in a world with pricing. Going deeply into debt for a megaproject and failing to consider how paying for it will reduce traffic is the opposite of planning.

No financial viability. At $5 billion or more, this will be the most expensive transportation project in this region for the next couple of decades.In theory, the project should be part of the region’s “financially constrained” regional transportation plan, but the budget documents prepared by the state DOT staffs show that they don’t know the actual cost of the project, and that there is a massive, $3.4 billion hole in the project’s budget. Moving ahead with no clear idea how the project would be paid for is opposite of planning.

The original CRC effort foundered a decade ago because there was no stomach for its excessive costs in either Oregon or Washington. Congressman Peter DeFazio famously declared the project to be a gold-plated monstrosity. In the Oregonian on August 14, 2011, Representative DeFazio said:

“I kept on telling the project to keep the costs down, don’t build a gold-plated project,” a clearly frustrated DeFazio said. “How can you have a $4 billion project? They let the engineers loose, told them to solve all the region’s infrastructure problems in one fell swoop… They need to get it all straight and come up with a viable project, a viable financing plan that can withstand a vigorous review.”(Manning, Jeff. “Columbia River Crossing could be a casualty of the federal budget crunch”, The Oregonian, August 14, 2011).

“I said, how can it cost three or four billion bucks to go across the Columbia River? . . . The Columbia River Crossing problem was thrown out to engineers, it wasn’t overseen: they said solve all the problems in this twelve-mile corridor and they did it in a big engineering way, and not in an appropriate way.”“Think Out Loud,” Oregon Public Broadcasting, August 18, 2011.

Ten years ago, the two state DOT’s squandered nearly $200 million on planning without first securing the needed funds for the project, and they are repeating this exact failed strategy today. Now, in their efforts to revive the project, after two years of work, the project has not developed a definitive financial plan, and its estimates of Oregon’s needed contribution have inexplicably jumped by more than $150 million in a month. ODOT and WSDOT are spending millions—$200 million is planned for staff and consultants before this project breaks ground—with no clear idea of how this will be paid for.

This amendment adds $71 million to the preliminary engineering (PE) phase of the IBR Program. With this change, the total available budget will change to $80 million ($45M from Oregon and $35M from Washington). The estimated PE cost to complete NEPA for the IBR program is approximately $135 million based on a completion of a supplemental environmental impact statement (SEIS) in mid-2024. Following NEPA completion, the IBR program will develop a program delivery plan and progress with right-of-way acquisitions and final design to prepare for the start construction in late 2025. The estimated PE cost for progressing final design to start the first phase of construction is estimated at approximately $70 million. In summary, the total estimate of PE to begin the first phase of construction is estimated to be approximately $205 million. This estimate is contingent on the scope of the IBR solution, as agreed to by program partners, that will be evaluated through the SEIS along with the scope of the program’s first construction phase. Right-of-way costs and construction costs are not included in this budget estimate.

[Chris Ford, Memo to Metro TPAC, “I-5:Columbia River (Interstate) Bridge: Requested Amendment to the 2021-24 Metropolitan Transportation Improvement Program.” Oregon Department of Transportation. September 24, 2021, aka ODOT/Ford Memo. Page 6. Emphasis added.)

The prospect for Build Back Better and a national infrastructure funding package is no reason to move ahead with a misguided, environmentally destructive bridge project. Oregon and Washington will get their share of these monies whether they build this project, or whether they choose to use these funds more wisely. A regional government that cared about the future would ask “what is the smartest possible use of $5 billion” rather than approving this project.

Cannibalizing maintenance to pay for megaprojects. This particular project is a particularly egregious example of how state DOT’s beg for money by complaining that they don’t have enough money to fix potholes, but then use any additional revenue they can find to build massive new projects that simply increase the maintenance burden. This project is no exception, ODOT is literally asking Metro to approve the reallocation of funds that would otherwise be used for maintenance to pay for planning the megaproject.

ODOT is reducing money for road maintenance and repair to hire consultants for this megaproject. ODOT’s own memo makes this clear.

This project change requires adjustment to the fiscally constrained RTP. Funds from the fiscally constrained Fix-It buckets in the RTP will be reduced to allow for the $36M ODOT funds to be advanced on this project. Memo with details was sent to Metro 9/17/21 by Chris Ford. We find the analysis is still applicable with the addition of WDOT funds since RTP focuses on Oregon revenue only.

[ODOT/Ford Memo. page 12, Emphasis added.]

Diverting money from maintenance funds to pay for a megaproject is the opposite of planning.

This is a pivotal moment for Metro. As former Metro President David Bragdon (who guided the agency through the original Columbia River Crossing) wrote in retrospect:

Leadership at ODOT frequently told me things that were not true, bluffed about things they did not know, made all sorts of misleading claims, and routinely broke promises. They continually substituted PR and lobbying gambits in place of sound engineering, planning and financial acumen, treating absolutely everything as merely a challenge of spin rather than matters of dollars or physical reality.

That history is important, because if you’re not honest about the patterns of the past, you are doomed to repeat them. Unfortunately, I understand that’s exactly what’s going on with the rebranded CRC: the same agencies, and even some of the same personalities who failed so spectacularly less than a decade ago – wasting nearly $200 million and building absolutely nothing – have inexplicably been rewarded for their failure by being given license to try the very same task, using the very same techniques of bamboozlement.

Metro has a choice: It can repeat the mistakes of the past and bow to the wishes of an entrenched highway building bureaucracy, or it can do its job, and live up to its professed values. It can plan. It can insist on accurate travel projections, it can demand a definitive finance plan, it can require that freeway construction be addressed comprehensively, rather than piecemeal, it can require that the vision for capacity be integrated with congestion pricing, and it can require a full financial plan before squandering more on planning this speculative project. And above all, it can insist that the region’s next multi-billion dollar transportation project reduce greenhouse gases, rather than increase them. Anything less would be the opposite of planning.