If so many people live in suburbs, it must be because that’s what they prefer, right? But the evidence is to the contrary.

One of the chief arguments in favor of the suburbs is simply that that is where millions and millions of people actually live. If so many Americans live in suburbs, this must be proof that they actually prefer suburban locations to urban ones. The counterargument, of course, is that people can only choose from among the options presented to them. And the options for most people are not evenly split between cities and suburbs, for a variety of reasons, including the subsidization of highways and parking, school policies, and the continuing legacies of racism, redlining, and segregation. One of the biggest reasons, of course, is restrictive zoning, which prohibits the construction of new urban neighborhoods all over the country.

But does zoning really act as a constraint on more compact, urban housing? Sure, some skeptics might say, it appears that local zoning laws prohibit denser housing and walkable retail districts. But in fact, city governments pass such strict laws because that’s what their constituents want. Especially within a metropolitan region with many different suburban municipalities, these governments are essentially competing for residents and businesses. If there were real demand for denser, walkable neighborhoods, wouldn’t some municipalities figure out that they could attract those people by allowing that type of development?

A 2005 study by Jonathan Levine—and explored further in Levine’s 2006 book, Zoned Out—seeks to answer this question. Are local governments just responding to “market” demand in ensuring that new development is low-density and auto-oriented? Or is there really pent-up demand for more urban neighborhoods that can’t be satisfied because of zoning?

Levine looks for the answer in two contrasting metropolitan areas: Boston and Atlanta. Boston, as a much older region, has a relatively higher number of dense, walkable neighborhoods, while in Atlanta, which mostly boomed after World War Two, urban neighborhoods are much more scarce. Levine hypothesizes that if dense housing is adequately supplied to match people’s preferences, you should find a pretty good match between the kinds of places people say they’d like to live, and the kinds of places they actually do live. But if zoning really creates a “shortage of cities,” then the greater the shortfall of urban neighborhoods, the worse the matchup between stated preferences and actual living arrangements.

This is an important wrinkle to the “revealed preference” arguments of many defenders of the suburban status quo. Recent Census population figures sparked what were only the latest of a long line of scuffles over whether, or to what extent, the “back to the city” movement is real. But if Levine’s argument is correct, measuring demand for urban areas simply by how many people end up living there is flawed, because some people who would like to live in more compact neighborhoods can’t do so because there aren’t enough to go around.

To begin his analysis, Levine classified neighborhoods in both the Boston and Atlanta metro areas according to their level of “urban-ness” on a five-point scale, with “A” neighborhoods being the densest and most urban, and “E” being the most sprawling and exurban. Levine and his researchers then conducted a survey of residents in each of the zones, asking about their housing preferences and satisfaction with their current housing situation.

In Boston, about 40 percent of respondents said they preferred denser, more pedestrian-friendly neighborhoods, while in Atlanta, just under 30 percent of respondents did so. (Auto-oriented neighborhoods were preferred by 29 percent of people in Boston and 41 percent of people in Atlanta, with remaining respondents neutral.)

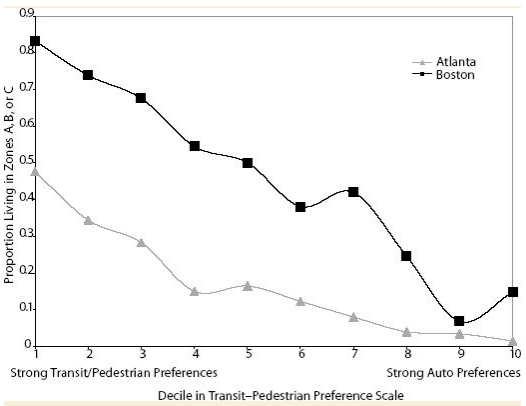

And how well did these preferences match actual behavior? Well, in Boston—where neighborhoods in the three most urban categories made up over half of all housing—83 percent of people with strong preferences for urban neighborhoods lived in one of these three urban zones. In Atlanta—where the same top three urban categories make up barely over 10 percent of all housing—just 48 percent of people with strong preferences for urban neighborhoods lived in an urban zone.

In fact, all down the line, people whose stated preferences were more urban were much more likely to actually live in an urban neighborhood in the Boston area than in the Atlanta area—suggesting that in Atlanta something might be preventing them from satisfying their preferences. At the same time, people who expressed preferences for the most auto-oriented neighborhoods were able to satisfy that demand the vast majority of the time in both regions—about 95 percent of those in Atlanta, and 80-90 percent of those in Boston. More rigorous tests prove that this difference is statistically significant.

This seems like strong evidence that there is a “shortage of cities” in Atlanta. Why, otherwise, would there be such a gap between the number of people who satisfy their preferences for urban neighborhoods in the Boston and Atlanta metro areas—and much smaller gaps between people who can satisfy their preferences for more car-oriented areas?

If this is correct, it helps explain a other issues we see. If urban neighborhoods are undersupplied compared to demand for them, we would expect to see urban housing go to the people willing to outbid other households, increasing prices relative to auto-oriented neighborhoods, which are more plentiful. In a place like Atlanta, lots of urban housing would have to be built before this bidding war could be ended, returning prices to a “normal” market level.

It’s also notable that this kind of “shortage of cities” can occur even where there is no overall housing shortage. Atlanta, for example, is not a particularly high-cost region, but it has mostly added new housing on the suburban periphery. So while there’s no bidding war for housing in the metropolitan area as a whole, there is a bidding war for more urban housing, making walkable neighborhoods more expensive than they would have to be. Boston is almost the opposite: walkable neighborhoods appear to be less undersupplied relative to auto-oriented neighborhoods, but the region as a whole has very expensive housing, suggesting that the total supply of housing is too low. Boston could help bring down housing prices by building any housing at all—auto-oriented or more walkable. (Though walkable housing would have lower total location costs.)

Levine’s study ought to be known by anyone who works in urban planning or housing. It’s one of the strongest pieces of evidence that “revealed preferences”—the choices that people actually make about where to live—actually reveal the limited choices that people are given as a result of restrictive land use laws.